“India is increasingly an important strategic partner and we’ll focus more attention on the Indo-Pacific where the gravity of international affairs is moving. The US-India relationship is a major pillar of stability and prosperity in that region.”

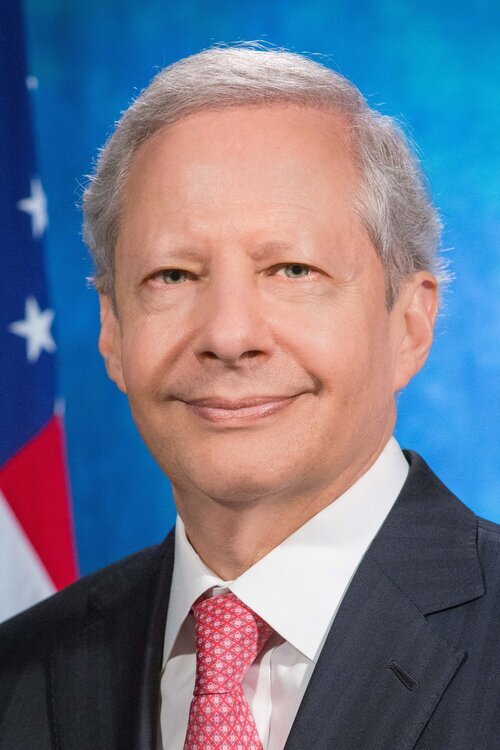

As former US ambassador to India, Kenneth Juster offers his perspective on the US-India relationship and its importance related to a rising China. He evaluates geopolitical risks from some of the top US adversaries like China and Russia and describes how American diplomats can help navigate 21st century challenges ahead. Ambassador Juster discusses American polarization, rise in nationalism at home and abroad, COVID surges in India, and the long fraught history of the India-Pakistan border conflict.

In 2017, Juster served as the Deputy Assistant to the President for International Economic Affairs and Deputy Director of the National Economic Council. He was a senior member of both the National Security Council and the National Economic Council. In this role, Juster coordinated the Administration’s international economic policy and integrated it with national security and foreign policy. He also served as the lead U.S. negotiator in the run-up to the G7 Summit in Taormina, Italy.

LISTEN AND SUBSCRIBE

SPEAKER

Kenneth Juster

25th United States Ambassador to India

2017-2021

MODERATOR

Anthony Scaramucci

Founder & Managing Partner

SkyBridge

TIMESTAMPS

0:00 - Intro and background

5:54 - History of the US-India relationship

9:09 - US-India-China dynamic

13:50 - US geopolitical risks

16:20 - Role of diplomats in the 21st century

18:18 - Assessing the national debt

21:10 - State of Russia and geopolitics

23:40- Capitol attack and the state of American democracy

25:51 - Immigration from India

29:30 - Rise in nationalism

31:50 - Challenges modernizing India’s economy

34:40 - COVID-19 in India

37:55 - India-Pakistan conflict

TRANSCRIPT

John Darcie: (00:07)

Hello everyone. And welcome back to salt talks. My name is John Darcie. I'm the managing director of salt, which is a global thought leadership forum and networking platform at the intersection of finance technology and public policy. Salt talks are a digital interview series with leading investors, creators, and thinkers. And our goal on these salt talks is the same as our goal at our salt conferences, which we're excited to resume here in September of 2021, registration just opened, uh, last Tuesday. So we're excited to resume those conferences, but our goal is to provide a window into the mind of subject matter experts, as well as provide a platform for what we think are big ideas that are shaping the future. And we're very excited that I'd welcome ambassador Kenneth Juster to salt talks. I ambassador just recently completed his service as the 25th us ambassador to the Republic of India.

John Darcie: (00:58)

He previously served in the U S government as deputy assistant to the president for international economic affairs on both the national security council and national economic council starting in 2017 under the secretary of commerce from 2001 to 2005, he was a counselor acting counsel of the state department from 1992 to 1993 and deputy and senior advisor to the deputy secretary of state Lawrence Eagleburger from 1989 to 1992 as under secretary of commerce. He co-founded the U S India high technology cooperation group. Uh, and he was a key architect of the next steps in strategic partnership initiative between the United States and India in the private sector. Uh, ambassador gesture has been a partner at the global investment from Warburg Pincus, uh, from 2010 to 2017, a senior executive@salesforce.com from 2005 to 2010 and a senior partner at the law firm, Arnold and Porter posting today's talk is Anthony Scaramucci. Who's the founder and managing partner of SkyBridge capital, which is a global alternative investment firm. Anthony is also the chairman of salt. And with that, I'll turn it over to Anthony for the

Kenneth Juster: (02:06)

Interview. Uh, John, thank you ambassador. Before I get started, John and I look like we're in hostage videos and there you are with this beautiful background. And so tell us what that background represents. Where is that in India and what is that beautiful building behind you, sir? Well, actually it's just my backyard in New York. Now it's called the water palace, uh, John Mahal and China or India. It's one of the many beautiful places to visit if you come to India. Uh, and I thought it was a nice background given that I had served for about three years. He's Friedman says in Basadur to that great country. And it's one of the more beautiful countries in the world before I get into your ambassadorship. However, I want to talk a little bit about your background. Where, where did you grow up, sir? What led you into public service?

Kenneth Juster: (03:01)

What did your career look like before you became the U the ambassador to India? Well, first of all, by the way, let me tell you it's a real pleasure to be with you here today, Anthony. I thank you for that question. Uh, I was born in Manhattan, but grew up in Westchester in Scarsdale. New York, graduated from Scarsdale high school. Uh, always had an interest in government and international affairs. Uh, after college, I did a joint degree in both, uh, the Kennedy school of government, as well as the law school at Harvard. Uh, and first served in government, uh, with one of my professors, Sam Huntington at the national security council in the late seventies. Uh, and that got me even more excited in working in the, uh, government and in foreign policy, went down to Washington as a practicing lawyer after a clerkship for a year at one of the large international law firms.

Kenneth Juster: (03:51)

And then, uh, one of the clients I worked with Larry Eagleburger, he can a deputy secretary of state. I was a junior partner. He asked me to come in, uh, to the government to work with him. That was a credible period of time. In 1989, you had the tenement square, you have the collapse of the Berlin wall, the unification of Germany, Iraq's invasion of Kuwait to collapse the Soviet union. And I worked with a wonderful team of people, and it really sold me on the possibilities of having a career where as you can in our country move in and out of government. I got to serve again in 2001 to 2005 as an under secretary of commerce in charge of issues for business and national security intersected. Uh, and then in 2017, I had not been involved in the campaign for the presidency, but, uh, when the Trump administration won, they did not have a deep team at that point.

Kenneth Juster: (04:49)

And I was asked, uh, by, uh, Gary Cohen, who had been the number two person at Goldman Sachs to join him at the white house as the Pressman charge of international economic affairs of the national security council, national economic council. Uh, I did that and then shortly thereafter, the opportunity to, uh, potentially be ambassador to India, opened up, my name was, uh, raised and I was, uh, very fortunate to be nominated and confirmed for that position later in 2017. Yeah. Listen, it's a great life story. And obviously thank you for your service. I want to step back a second for some of the Americans that listened to us here on saltbox that may not know as much about India as you do. And I want you to tell us the story of India, where India fits into the whole economic system, the geopolitical system. Why should us citizens be concerned about our, our relationship with India?

Kenneth Juster: (05:53)

Well, India became independent and, uh, August of 47 at the time, it was the partition of India and Pakistan. And it was a leader of the leader. Really it's a non-aligned movement during the cold war, uh, despite being in a non-aligned position, uh, over time, it, uh, tilted somewhat toward the Soviet union and Trump's of supplying its weaponry and military equipment in part because the United States also tilted toward Pakistan. The U S was still involved with India often in a, uh, area of developmental assistance, cyber cultural assistance. I'm like, uh, but the relationship was not particularly close. Uh, uh, with the end of the cold war, obviously the Soviet union, uh, disbanded, uh, you were starting to see, uh, immigration, uh, from India to United States and the beginning of an Indian American population. I mean, it existed before then, but it really began to take off more India, then tested some nuclear weapons, uh, in 1998 and received, uh, from the United States and other countries as severe sanctions for doing so.

Kenneth Juster: (07:04)

But at the end of his, uh, president Clinton's term, we took a trip to India, really tried to, uh, warm up the relationship. There was still the nuclear issue that was of concern. And when president George W. Bush came into office in 2001, he and Indian prime minister Bosch pipe at that time really felt that the world's oldest democracy United States and the world's largest democracy, and they should have a better relationship, but you may also recall India, Indian companies and individuals have been involved in the Y2K fix. So Americans were increasingly exposed to India and that really began the transformation of the relationship. I was fortunate to be involved because one of the things that India was interested in was access to, uh, sensitive us technology to help its economic sector is says civilian space sector and civilian defense sector, or somebody in military or not. I shouldn't say so the military, but, uh, uh, military sector to a certain degree as well.

Kenneth Juster: (08:07)

And, uh, I was, uh, at the intersection of those issues. And so it became involved in this transformation of the, uh, relationship. India is not an ally of the United States. It's not an adversary, but it's an increasingly important strategic partner. And as we have now focused more attention on the region, that's known as the Indo-Pacific and we're really the center of gravity of international affairs is moving the U S India relationship is a major pillar of, uh, hopefully stability and prosperity, uh, in that region. So we've really had an increasingly close relationship over the last 20 years, and it's been bipartisan, uh, and it's, uh, had the supportive parties, uh, across the aisles in both countries. And, uh, each administration has built on the successes of the previous one. And of course we have our tension now with China and China and India obviously have their issues, explain that triangle to people that are perhaps not as familiar with it.

Kenneth Juster: (09:10)

Well, first of all, India is in a very different geographical and historical position than the United States. China is on its Northern border, and it stretches very far on a supported that still remains undefined, uh, and, uh, Indian China have a relationship that goes back thousands of years, but they did have a war in 1962, uh, relating to the border issues. And they've tried to manage the relationship since then. They've had a series of agreements and protocols as to how to, uh, deal with water matters. Uh, they've interacted increasingly economically, but in the last several years, the Chinese have continued to be, uh, sort of aggressive on the Northern border. Uh, in 19 2017, they occupied territory in what's called [inaudible], which is an area for India, China, and Butan meat. And then in 2020, they amassed 50,000 troops on the Northern border. And so that has really raised, uh, concerns in India.

Kenneth Juster: (10:12)

And I think shattered a certain degree of trust that the Indians had with the Chinese, certainly the border issue, which has been compartmentalized and kept separate from the rest relationship does now, uh, undercut the relationship India is trying to disentangle itself somewhat from the chief economic relationship with China, struggling in the area of technology. And so it's a, it's a very sensitive dynamic in that region. Then you really have China, India and Pakistan, three nuclear, uh, countries all next to each other and its severity a potentially dangerous area of the world, but also one that, uh, with the world's largest populations and large economies and a tremendous amount of international trade and very dynamic and critical region. So I want you to react to this ambassador, the, uh, and these are perceptions and perhaps some of these perceptions are not factual. So clear it up for me if, uh, their perceptions.

Kenneth Juster: (11:11)

Um, but I would, I would say in general, American business leaders, uh, we view our relationship with China as competitive somewhat adversarial. There are politicians that would take it a step further and say that those tensions are, uh, on the edge there, if not, um, the beginnings of a cold war. Um, and there's some Imperial fears related to China. However, there doesn't seem to be those fears related to India. Uh, I want you to react to that, that I get any of that, right. Or, uh, what is the reality on the ground? Well, the Chinese have a very different form of government and India is autocracy and Chinese behavior. Recent years has been increasingly expansionist in that reach in the south China sea directed toward countries in Southeast Asia, east China, sea against India on the India against Japan, I'm sorry, on the Northern border with India, uh, in Butan, they've been aggressive, uh, that has really infiltrated in many ways, countries of south Asia, they've obviously in their own, uh, area have been increasingly aggressive in Taiwan, Taiwan, Hong Kong.

Kenneth Juster: (12:24)

And so, uh, this has gotten the attention and concern of the country and the region. India is a democracy. It has not indicated or exhibited expansionist of behavior. It set fascinating country. That's incredibly diverse. It's really many countries rolled up into one, but it's a country that we share many values with. There is tremendous people to people relationship there, approximately formerly in Indian Americans in the United States, uh, there's constant travel back and forth between the two countries. We, uh, processed over 1 million visas a year, uh, from India over 200,000 Indian students go to United States to get educated. So it's a very different relationship and that's the country that we want to build a, uh, increasing, uh, uh, future with in terms of trying to have a stable Indo-Pacific and a more stable, uh, world water. And we see India as a key partner, uh, in that process, no one wants to have a conflict with China, but it's an increasingly, uh, competitive, uh, relationship.

Kenneth Juster: (13:30)

Uh, prior to your role as ambassador, you were at Warburg Pincus, I think for six or seven years, uh, one of your jobs there was to assess geopolitical risk. And so step back for our salt talk, viewers and listeners, and tell us where the geopolitical risks are to the United States and to our industries. Okay, well, this is really a time of great change in the international system. The tectonic plates are moving, uh, led primarily by the rise of China. Uh, I mean, there's always the question of when a new great power rises, can that be done peacefully when the existing international system, or will that create tensions and potentially even conflict, but the rise of China and, uh, uh, the potential, uh, concerns that, that, uh, uh, companies that is certainly one of the, uh, central geopolitical risks that people need to, uh, deal with and focus on Russia, uh, has been a revisionist country and is engaged in activity that is increasingly of concern to the United States, to countries in Europe and elsewhere.

Kenneth Juster: (14:38)

That's a major risk. I think even in the west, the rise of nationalism post COVID 19, a lot of countries are saying, how do we cut our dependencies and other countries? How do we bring back, uh, economic activity to our country? What that means for, uh, international trade and economic interaction is going to be a challenge and really defining the, the rules of the road for the world order going forward. Many people would say that the liberal system that developed after world war two is no longer really attuned to today's challenges. And so how do we develop a new system that enhances prosperity and security and hopefully avoid conflict as you have the uplift ration of weapons of mass destruction, and you have a bunch of other challenges in the global common, such as the pandemic we're dealing with right now, although on the flip side, however, there are massive, positive technological changes taking place.

Kenneth Juster: (15:40)

Uh, we're moving more at the renewables. We've got the introduction of 5g and all the massive technological information flow transformation that will take place as a result of that. And of course, in the bio technological world, we're doing things like M RNA. And so paint a picture for us of how our diplomats can help calm down the world, if you will relieve some of these tensions. So this great prosperity that's ahead for us technologically can, can happen in a peaceful way. And also obviously in a deep way, economically, where we can share it among the classes and societies. Well, as you say, technology is truly changing the world and as it penetrates every industry, it can have a very positive impact, but technology misuse can also have a negative impact. Our attorney governments can use technology to suppress their people. You can get track of people's privacy and invade that as well.

Kenneth Juster: (16:40)

And I think what diplomats can try to do, uh, working hand in hand with the business community is really developed the rules and standards for the uses of technology and, and, uh, future, uh, economic discussions we'll have to deal with the digital economy. What did we do in terms of a FinTech financial technology to ensure that they can have more transactions, but at the same time that these are secure and don't get infiltrated by people who want ransomware things of that nature. So technology is neutral. It can have a tremendously positive impact if it's properly administered and regulated, uh, and hopefully minimal regulation, but there are certainly important public policy issues of privacy and security, cyber security, uh, but it can be very damaging if because of, uh, increased technology, the country can go in and paralyze your infrastructure through a tax on that technology.

Kenneth Juster: (17:40)

I think it's well said, and DAS, I want to, I want to put your, uh, economist hat on for a sec and get your reaction to this. We were approximately 8 trillion of deficit spending from 1776 to 2008, from 2008 to 2021 and 13 years. We've added about $20 trillion of debt. So we're now clicking at a $28 trillion budget deficit for the United States. So, so we we've had modern monetary theorists on that are saying not, not to be worried about our $28 trillion deficit. Are you worried about it? Yeah, I'm worried about it for a few reasons. First of all, the U S economy is the most resilient economy in the world. Uh, we have a highly entrepreneurial, uh, population. We are able to raise capital and deploy it very quickly. People are high risk takers can get rewarded for that. And so I think the U S economy will do quite well.

Kenneth Juster: (18:45)

And, uh, even in this situation post COVID, I think people have been impressed at how quickly it is covering. So we need still targeted safety nets and potentially stimulus, but I worry that we've offered it. And as a consequence, uh, you have a lot of money in the financial system that can lead to inflation, which will not be beneficial for anybody, uh, that can also, uh, lead to higher taxation to support all of the spending, which will, I think, stifle economic growth. And finally, uh, all of this, uh, deficit spending will be, uh, a real burden on future generations where they're going to have to spend a lot of their budgets to repay, uh, the London. So I think as you say, we have, uh, seen a tremendous amount of new, uh, spending in the last several years and deficit spending and it is troubling, and I hope that it doesn't really become a drag on the economy, which otherwise I think would be very dynamic in this country.

Kenneth Juster: (19:52)

Yeah. Listen, I, I don't know. I got trained in economics 35 years ago. I'm worried that I'm being told not to be worried about it. I wanted to get your reaction to all of it. Yeah, no, I think intuitively you have to think about your own household. Would you be comfortable if you had that much that running your own expenses and a country is made up of a lot of households. And so I think it does raise serious concerns and we've really broken through barriers that years ago. We never anticipated, but even be reaching. And, and we've had, we, we had a long-term thinking back in the day and we had people that were, you know, I just read a Hitchcock's book on Dwight Eisenhower talking about how seriously he took that budget and how sharp he was with a pencil. It seems now that we're, we're, we're over promising and under delivering, at least in that category.

Kenneth Juster: (20:47)

I want, I wanna, I want to switch gears for a second and ask your opinion of Russia because of your experience in the diplomatic Corps, but also your experience as a world leader and, uh, uh, an investor, uh, give us your, uh, synopsis of where we are with Russia. And where do you see Russia in terms of its geopolitical footprint? Well, after the collapse of the Soviet union, there were great hopes that Russia could be integrated into, uh, the west. And, uh, that process unfortunately, uh, uh, has not worked, uh, successfully. And I think, uh, Putin, uh, represents, uh, in many respects, someone who bemoans the collapse of the empire that Russia had developed and through the Soviet union, and he has become over time and increasingly revisionist leader and Russia has, uh, engaged in whole range of behavior. That's increasingly troubling. And it almost seems as if their, a modus operandi is to Crow and do things that they feel are just under the threshold that we'll get a nature reaction from the United States and other countries yes, for imposed sanctions.

Kenneth Juster: (22:03)

But we don't really, uh, put a red line down and say, this is unacceptable, and we're going to reverse the behavior. And the challenge for the United States working with its European allies is not to want to, uh, create a conflict with Russia, but to make very clear that there's conduct, that's not acceptable. And that this process of, uh, probing and doing things that are increasingly, uh, uh, against the interests of the United States and Europe, including cyber attacks, including interfering with elections, including the activity, uh, in Ukraine and elsewhere, this has got to come to a stop. And that's really one of the major challenges, uh, for the Biden administration. One of the geopolitical challenges that you mentioned, because if this behavior is allowed to continue, it encourages other countries to engage in that sort of behavior as well. I, I appreciate it. Ambassador. I'm gonna, I'm gonna make sure that John gets some tough questions like about the Indian Pakistan border, you know, stuff like that.

Kenneth Juster: (23:07)

I, I want you to like me and hopefully John will say some prickly things and you'll be annoyed with him, but I have one, one last question for you. And that is about our, our democracy and the insurrection that took place on January 6th, which, uh, uh, four two was my birthday. I was watching celebrating my birthday and watching a insurrection at the nation's Capitol. And I feel that the democracy is under threat. And so not to superimpose my ideas on you. What do you feel about this situation? What are your thoughts there? How we can heal the country and possibly try to figure out ways to remit the country and unite the, I think there are several issues that you raised and I want to try to dis-aggregate them. I think at the broadest level, in terms of our democracy, I would say much like our economy.

Kenneth Juster: (23:56)

It's, it's very resilient. We have strong institutions I've seen around the world countries that don't have institutions that come anywhere close to what we have strong traditionary. And we have a strong, uh, media, uh, sector. We have strong civil society. So I don't think that democracy itself in the United States is under threat. But I do think is of concern is that it's increasingly polarized our political system and therefore dysfunctional. Now, maybe you could say that makes it under threat. I don't think the system is dying to collapse, but I don't think it's fricking nearly as effectively as it needs to, especially to address the complex challenge that we have. And unfortunately it sends a negative signal to other countries around the world that democracy is not a, an effectively functioning system. And it's utilized by countries such as China to say, we have a better alternative system, which is sort of state capitalism.

Kenneth Juster: (24:53)

So the challenge for us is how do we, uh, begin again to work, uh, as a whole, uh, with, uh, people from both sides of the aisle, trying to make compromises, to advance our interests collectively, and to stop enacting a legislation that is supported only by one side of the other, and then gets reversed a few years later when the other side, uh, is, uh, uh, controlling the Congress and executive branch. So the democracy and abroad way, I think is resilient. And still, we have stronger institutions than any country in the world, but I do think it's increasingly challenged by the political polarization that has made its implementation, uh, less functional than it should be. And well said, hopefully we can, you can get there. Um, uh, but, uh, John, let's go here. Okay. Ask the super tough questions. Okay. Because what happens to me ambassador is we leave these Saul talks. Everybody likes John, and they think I'm asking all the tough questions. So come on, John, dig in here, get some spikes and those questions,

John Darcie: (26:00)

All right, I'll start with immigration, uh, ambassador. So I believe there's something around 4 million Indian Americans in the United States. You know, many of them are the heads of our major hospital systems or tech companies. You have the heads of, of Google and Microsoft today, or Indian Americans. It's obviously been an exchange of people and ideas and commerce between the two nations that has been very fruitful for everyone involved. And I want to talk about the immigration issue a little bit. I think within the Trump administration, obviously they, they tightened up our immigration policies a little bit. Uh, you know, the Biden administration is still grappling with how to both encourage immigration, but also maintain some control and sovereignty over our borders, frankly. But what is the right immigration policy? Do we have the right policies to continue to attract the best talent from the tech world? If you were in charge, how would you adjust, uh, the current stuff?

Kenneth Juster: (26:51)

Well, first of all, I want to, uh, highlight what you said is that Indian Americans that have come to this country have made a great contribution across a whole range of sectors, whether it's been medical sector, legal sector, and certainly in the technology sector and it's, and it's really benefited those countries because it's been a two-by-two flow of, of, of ideas, uh, and, uh, people going back and forth. Uh, many of these, uh, Indian Americans have come to United States through what's called an H one B visa mature, uh, is a program that began in 1990 to really get a high quality people, to fill jobs in the technology sector that cannot otherwise be filled by Americans. There are 65,000 slots for H one BS and another 20,000 for people who have a master's degree. This is a global program. That's open to people from around the world, but the Indians have been able to garner on average about 75% of the spaces that has not changed over time.

Kenneth Juster: (27:56)

The H1B visa program is still in place. It's still 65,000 plus 20,000. It was suspended during the last half of 2020, because COVID had put so many people out of work, but there was a sense that we needed to give some priority to Americans, but the program is back in place. And while there have been certain tightening of the rules and regulations, so that it really getting high quality people, and they're not, there's not a gaming of the system is still means that about 70 to 75% of the visas go to Indian people. And many of those people then ultimately become a us citizen. So I think it's in terms of that policy, it's been a great success, uh, and, uh, I'm delighted that India sends its best people to our country to contribute to our economy. I think the challenge for India is to create conditions in its own countries, that some of these wonderful people want to stay there to develop their career and their entrepreneurship and their outpatient rather than contribute to our economy. But the immigration policy that has been relevant to Indian Americans, the H1B, I think, has been a very, a substantial success. Do

John Darcie: (29:10)

You read all about what Anthony mentioned earlier? This rise in nationalism and populism and some of the polarization that exists in the United States might turn people from somewhere like India off from coming to this country and setting up their business or coming to work in our, uh, economy. Uh, do you think that issue is,

Kenneth Juster: (29:30)

Yeah, look, I think that, as I mentioned earlier is a very important issue, especially coming out of COVID-19. The question is going to be what lessons countries learn from COVID-19 will it be one of the increased nationalism we need to close our borders. We need to try to develop everything internally. Will the pendulum swing from a very interdependent economic relationship that's existed throughout the world to one that tries to cut off, uh, dependencies. I think what you really need to do is develop dependencies, but trusted partners so that you no country can do things alone, but this sort of nationalism and we've seen in India, uh, what's called self-reliance and the Indians are quick to say that this does not mean it's going to limit their level of global interaction, but it is saying that we want to be increasingly self-reliant. We want to make sure that supply chains are not dependent on countries that have concern.

Kenneth Juster: (30:29)

And so have that will have an impact on India. How some of the concerns in the United States, uh, uh, about jobs and security will have an impact still remains to be seen. But the fact is economic interaction movement of people, flow of technology, uh, movement of currencies, and, uh, uh, capital markets is so integrated, uh, internationally that you're not going to be able to turn that back, which is even by the way, why, uh, the relationship with China is very different than what we saw during the cold war with the United States. So the Chinese economy is very much integrated with the rest of the roles. We're going to have to figure out how to manage issues that are of concern, rather than think that somehow we're going to be able to disentangle everything and separate, right? So,

John Darcie: (31:17)

Uh, several years ago, India is a very cash dominant economy. You probably know the statistics better than I do, but I know it's a very cash dominant society. The government went through an experiment several years ago, where they tried to basically repatriate a lot of the cash that was on the street and digitize a lot of the economy. How successful were they in that? What did we learn from that experiment? And what is the current state of the Indian economy in terms of modernizing and trying to root out what they perceive as I think non-payment of taxes and just an overall archaic infrastructure around their economy?

Kenneth Juster: (31:51)

Well, what you're referring to is something known as the monetization and which I'm very short notice, all sorts of forms of certain denominations of currency were outlawed. And in hindsight, it created a, uh, a real problem in India because suddenly a lot of people's law operated outside the normal economy, but that's how, uh, people who work in India often do operate on and at subsistence levels over suddenly put out of work and, uh, their businesses suffered. And so it had a substantial, uh, downsides, economically. It was meant to sort of root out corruption, uh, perhaps it had some positives in that respect, but, uh, clearly what we've seen is an increasing move, uh, to go to more of a economy. We using credit cards and other types of payment systems. And this is happening in India as well. Whole payments process industry is taking off.

Kenneth Juster: (32:49)

Obviously it's the degree, things are done that way. It does lessen the possibilities of corruption. And I think this is where the world is going. What it needs to happen now is folks who work in the regulatory area to better understand the ramifications of this, and to make sure that it can be done in a way that, uh, does not allow for laundering of money for illegal payments and for other types of issues. But Raul moving in terms of, uh, technology transforming the financial sector, I'm trying to do it in a way that will be more efficient for people and, and, uh, without fraud and corruption better enable, uh, prosperity along the way. So

John Darcie: (33:29)

I want to talk about COVID-19 for a second. We obviously over here in the United States saw a lot of horrific stories, the same noise we did inside of our own borders about things that were happening related to COVID-19 in India. They had a big wave of infections, sort of after things started to die down here in the United States are still working on increasing their vaccination rates, how dire, uh, was, and is the situation related to COVID-19 in India. And what do you think the country will have learned from, from that period about, uh, public health challenges and new healthcare models?

Kenneth Juster: (34:01)

Well, let me sort of, uh, review what have been two phases. I think of dealing with COVID-19 initially, uh, in March of last year, uh, the prime minister in post, a very severe lock than maybe the most severe of any major economy in the world, other than China, uh, for really it was six weeks and then it slowly started to be loosened up, but state of the lockdown or broadly stayed on for a few months and this sort of several purposes, the Indian health system itself is less well developed. There are less beds available per person and other medical supplies and optimally, it would be the case. And during this initial period enabled India to build up its supply of protective equipment of ventilators of hospital beds and availability. And so when people started to have COVID symptoms, the healthcare system was able to deal with it without being completely overrun.

Kenneth Juster: (34:58)

India did have, and given its population, it's a country, that's about a third, the size of the United States, the population density or within the population about four times our country. So you can imagine how dense it is. They did have a significant number of cases, but were able to manage it. And for whatever reason, there was a lower fatality rates. Some people think because India has perhaps a very young population, 65% of the people that are under the age of 35, maybe because people were exposed to SARS in 2003, and it built up immunities to this fires. And maybe because people had just been exposed to other illnesses and have immune systems for whatever reason, even with a substantial number of cases that were not as many fatalities. And by the time I left India in January of 2021 cases had really gone down and things looked like they were in good shape.

Kenneth Juster: (35:50)

Unfortunately, I think there was a overconfidence perhaps that, uh, the, the COVID problem and solved and people in the government let their guard down. There were political rallies when there were four major state elections and an election in union territory. So you had hundreds of rallies for people who are without mass and close quarters. You had a major religious, uh, pilgrimage festivity called the Q mail of it was moved up a year from 2022 to 2021 over a million people got together there. And so they suddenly had a spreading a big second way, and you still have to add new variants, uh, uh, one variant that seems to hit younger people and also spreading more rapidly and there's opposite concern. It could even come to our country. And so India has suffered greatly during the second way. It's the numbers. In fact, it may well be underreported.

Kenneth Juster: (36:42)

And while I think it's plateaued out in the major cities and it's getting better, the real concern now is that it's stretched the rural areas, where there really is a very, uh, poor health infrastructure. And that we could see, unfortunately, a more tragic deaths along the way India has, I think, learned a lot. Uh, it had initially been exporting vaccines. It's now trying to focus more on building up its own inventory and getting its own population facts. And I still think only about 3% of the population has received two vaccine shots. About 13% of the population has received one, but that's still a substantial way to go, uh, for the country. So this will continue to be a challenge.

John Darcie: (37:23)

Last question I want to ask, ask you it's about India, Pakistan. So when people go around

Kenneth Juster: (37:27)

The world and they try to identify the real hotspots where we could see the potential for armed conflict and potentially nuclear conflict, India, Pakistan seems to be one of the top ones on the list. So how concerned are you about relations between those two countries? Where do they stand today relative to sort of the historical ebbs and flows and tensions between those two countries? And again, how concerned are you about the bubbling up of tensions between India and Pakistan? Oh, the relationship between India and Pakistan has always been a difficult one beginning with partition in 1947, they've had four wars and 47 and 65 and 71, uh, and in 99. And, uh, there has been, uh, recent years increased cross border terrorism from Pakistan to India. And this is a area because you have two nuclear states that always, uh, presents, uh, risks more recently when India had a further focus on problems in the north with China, their nightmare scenario is that they have a two front conflict with China in the north and Pakistan in the west and the Indians and the Pakistan have been able to reach agreement in February of this year to honor all of the peace and sort of ceasefire arrangements on the line of control that separates the two countries, but they still need to try to work out a better modus operandi and to have economic development when prime minister Modi and become development in that region and prime minister Modi came into office.

Kenneth Juster: (39:04)

He didn't invite the Indian prime minister, the Pakistani prime minister to his inauguration. He later visit our prime minister on his birthday and they sought to try to move the relationship forward. But then there were some terrorists and Smiths and it's undercut that. And I really think they need to deal with solving the cross border terrorism issue to promote greater stability and economic opportunity in that region. But this continues to be a sort of an area of tension. They countries do have a dialogue and back channel operations to try to keep things under control, but again, something can flare up and, uh, lead to a problem. So I think the whole region, as I mentioned, all Europe, India, Pakistan, China is one that the world needs to keep a sharp eye on.

John Darcie: (39:56)

Well, ambassador Kenneth Juster. Thank you so much for

Kenneth Juster: (39:58)

Joining us here on salt socks. I think more than anyone right now, uh, in the American power structure, you've done so many things to contribute to this great partnership and friendship between the United States and India that I think will be increasingly important, uh, in the years to come. And we have you, uh, in part to thank for that, that partnership. So thank you so much for your service. Thanks for joining us on salt talks, Anthony ever final word for the ambassador before we let him go. One of our live events. So we've got our next one coming up in September DAS that are at the Javits center. So thank you very much, Anthony and Jocelyn, real pleasure speaking with you this morning. Thank you everyone for tuning into today's salt. Talk with ambassador, Ken adjuster, just a reminder. If you missed any part of this talk or any of our previous salt talks, you can access them all on demand on our website. It's salt.org backslash talks or on our YouTube channel, which is called salt too. We're also on social media. Twitter is where we're most active at salt conference, but we're also on LinkedIn, Instagram and Facebook as well. And please spread the word about these salt talks. If you find them interesting on behalf of Anthony and the entire salt team, this is John Darcie signing off from salt talk sport today. We hope to see you back here against them.