“I believe capitalism is the economic system that best goes with liberal democracy. That said… the way in which the wealth gap and inequality is going, especially the last 25 years, is downright scary and threatens the stability of our democracy.”

Congressman Brendan Boyle discusses the damage caused by 25 years of growing wealth gaps and inequality, and his proposed wealth tax legislation as a countermeasure. Congressman Boyle touches on issues around federal deficits, gun control, infrastructure and vaccinations. He expresses concern about the state of America’s democracy, noting the numerous stresses placed on institutions during Trump’s time in the White House, punctuated by the violent January 6th attack on the Capitol.

He was elected to the Pennsylvania state legislature in 2008, becoming the first Democrat to ever represent his legislative district. Now in his fourth term, Congressman Boyle represents the 2nd congressional district of Pennsylvania which is fully enclosed within the City of Philadelphia. He currently serves on the House Ways and Means Committee, and on the Select Revenue Subcommittee and Trade Subcommittee thereof. He also serves on the House Committee on the Budget. He previously served on the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the House Committee on Oversight and Government. Congressman Boyle also serves as a member of the United States Delegation to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly.

LISTEN AND SUBSCRIBE

MODERATOR

SPEAKER

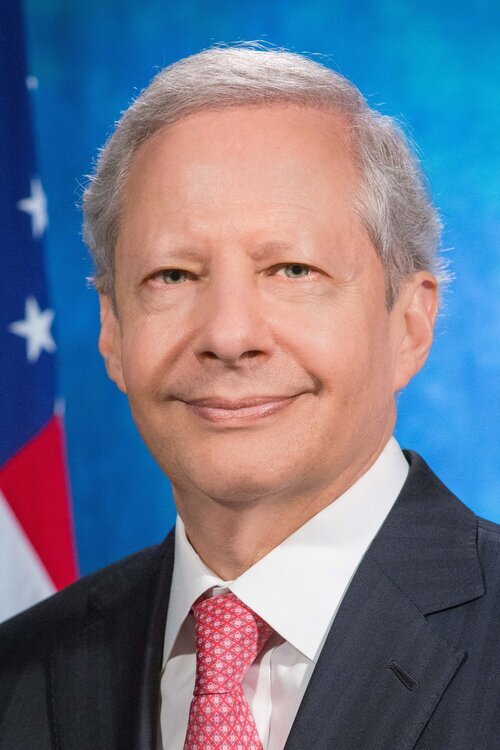

Brendan Boyle

Congressman

D-Pennsylvania, 2nd District

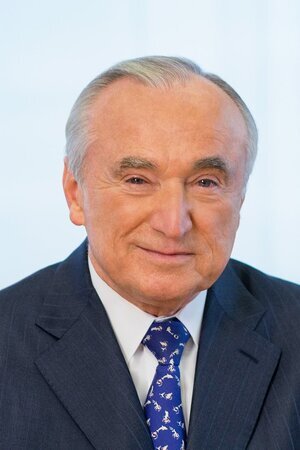

Anthony Scaramucci

Founder & Managing Partner

SkyBridge

TIMESTAMPS

0:00 – Intro

2:48 – Background and choosing public service

6:16 – Wealth tax

9:32 – American tax system

12:55 – Deficits and debt

18:42 – Implementing a wealth tax

23:36 – Gun control

27:25 – Infrastructure bill

29:26 – Vaccinations, mandates and misinformation

33:05 – Twitter, Taliban and free speech

35:15 – Bipartisan support in checking China

36:40 – 1/6 insurrection and stresses on America’s democracy

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

John Darsie: (00:07)

Hello, everyone and welcome back to SALT Talks. My name is John Darsie. I'm the managing director of salt, which is a global thought leadership forum and networking platform at the intersection of finance technology and public policy. SALT Talks are a digital interview series that we started in 2020 with leading investors, creators and thinkers. And our goal on these talks is the same as our goal at our SALT Conferences, which we're excited to resume here in September of 2021 in our home city of New York. And that goal is to provide a window into the mind of subject matter experts, as well as provide a platform for what we think are big ideas that are shaping the future. We're very excited today to welcome you to a SALT Talk with Congressman Brendan F. Boyle. Congressman Boyle was born and raised in the city of Philadelphia, is the son of an immigrant and Congressman Boyle's father was a janitor for SEPTA and his mother was a school crossing guard.

John Darsie: (01:06)

The first in his family to attend college, he attended the University of Notre Dame and later graduated from Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government with a master's degree in public policy. He was elected to the Pennsylvania state legislature in 2008, becoming the first Democrat to ever represent his legislative district. Two years later, his brother Kevin was also elected to the state legislature, making them the first brothers to serve together in the state house. In 2014, Congressman Boyle pulled off and upset and beat three better funded rivals to be elected to the United States Congress.

John Darsie: (01:43)

Now in his fourth term, Congressman Boyle represents the second congressional district of Pennsylvania, which is fully enclosed within the city of Philadelphia. He currently serves on the House Ways and Means Committee and on the Select Revenue subcommittee and Trade subcommittee thereof. He also serves as the Vice Chair of the House Committee on the Budget. He previously served on the House Foreign Affairs Committee and the House Committee on Oversight and Government. Congressman Boyle also serves as a member of the United States delegation to the NATO Parliamentary Assembly. Congressman Boyle is the founder and co-chair of the Blue Collar Caucus, which advocates for working families by addressing wage stagnation, job insecurity, and the future of work. Hosting today's talk is Anthony Scaramucci, who is the founder and managing partner of SkyBridge Capital, which is a global alternative investment firm and with that, I'll turn it over to Anthony for the interview.

Anthony Scaramucci: (02:34)

So Congressman it's a big honor to have you on. I've got so many different questions for you, but I think the most important one for right now is your background. Tell us about your background. Why did you make a decision to go into public service?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (02:48)

Yeah, well, thanks for having me on. I really appreciate it. Anyone who follows me on Twitter knows my fandom for all the Philly sports teams, knows that I am Philly guy through and through. I'm born and raised in a row home in one of Philly's typical blue collar neighborhoods. My dad came from Ireland when he was 19, spent most of his adult life working blue collar jobs in a warehouse in south Philly and then later as a janitor for our city subway system. And my mom was a stay at home mom, but also worked part time as a crossing guard. So I'm, and I know it sounds almost stereotypical, but really their American dream was work hard, have stable jobs, send their kids to college, and I've been able to be fortunate and live that. Now in terms of how running for office-

Anthony Scaramucci: (03:47)

Yeah, I'm going to stop you for a second, because it's an amazing story. It's a classic American story. I remind everybody it's an immigrant story, and you and I are products of an immigration story, but to be a public servant is tremendous amount of sacrifice. Obviously, I could only do it for 11 days before I was ejected, but here you are, you've made a great career of it and it's coming with a lot of sacrifice to your family. So go ahead. Tell us why.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (04:14)

Yeah, so from as early as I can remember, and this really does link. You might identify with a lot of this, Anthony. It really does come from growing up in a household that the American dream was gospel. I mean, we had two religions, we were Catholic and we believed in the American dream, and both were held up as almost like religious faiths. I mean, one obviously is, but then the absolute firm belief in America that you can do anything, that is work hard. You can get ahead. We're sacrificing for you. I never even stopped and questioned that. It was just accepted as a fact like two plus two equals four is a fact. So public service plays into that. I mean, it goes along with it. And then specifically for me, as early as I could remember, I love politics and I love sports.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (05:10)

And I followed them both very closely when I went to college. I then major in government. But funny enough, as I was graduating from college and this was the boom economy of the 1990s, I was questioning how realistic is me coming from where I come from, actually running for office. How do you even go about that? I didn't know anyone, literally didn't know anyone who was in politics. So I went the normal business route, did that for a couple of years, really didn't feel too fulfilled. And then right around the time of September 11th, actually the afternoon of September 11th, I decided that this was the course that I wanted to take with my life.

Anthony Scaramucci: (05:58)

Super admirable. I appreciate your service to the country. I know hard these things are. You recently co-sponsored the Ultra Millionaire Tax Act alongside of Senator Warren. Why do you think a wealth tax is the best approach to solving the inequality?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (06:16)

Yeah. So let me back up for a second because, oh well, I'll say that the morning I did that, that afternoon, I ran into a good friend of mine, a colleague who's more of a moderate Democrat and he and I worked together and agree on a lot. And he was joking or half joking, half serious. He said, "Boyle, what the hell happened to you? You've become a socialist now?" And the answer is no. I firmly believe in capitalism. I believe capitalism is the economic system that best goes with liberal democracy. That said, if you look at our tax system right now, it actually asks a lot out of wage earners, particularly upper middle class wage earners that live in very wealthy Metro areas, New York, San Francisco, Philadelphia, et cetera. So the folks who are doing well, but are by no means Warren Buffett, or maybe you're making $500,000 a year and are living right outside New York city, when you factor it all up, federal, state, local, et cetera, they're probably paying an effective tax rate of close to 50%.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (07:27)

And yet then when you talk about people worth hundreds of millions of dollars, even billions of dollars who mostly have passive income, they can game the system in such a way that their annual tax bill is literally zero or close to it. I mean, one classic example. I think Carl Icahn even talks about this, the way he simply, he makes sure every year, he doesn't necessarily realize the gain, borrows against the paper gains. And right there, you have no tax liability. In fact, you have a deduction with the low amount of interest that you're paying. So what I'm saying is, "Hey, our tax system is actually screwed up. It's too skewed." And this might be a slightly different argument than say, like an Elizabeth Warren would make. But my view, we actually need to move closer to more of a hybrid system that wait a minute, we're missing a whole bunch of in reality, is income and is wealth that isn't getting taxed.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (08:28)

And yet we're asking a lot out of middle-class people and even upper middle class people. So that's one reason for it. The other reason is the more obvious one. And I say this as someone who again firmly believes in the American dream, but believes that the way in which we're going with this wealth gap and inequality, especially over the last 20, 25 years is downright scary and threatens the stability of our democracy. And I do think there's actually a link. I want to be careful here. It's not a straight link, but there is somewhat of a link between the overall decline of the size of the middle class over the last couple of decades and the sort of political instability and division that we're seeing in our country.

Anthony Scaramucci: (09:15)

So there's a lot to chew on there. So let's break it down together. 1913, we developed an income basis to our taxation, not an asset basis. Why do you think we did an income basis as opposed to an asset basis?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (09:33)

Yeah, well I mean, I would have to go back and ask Woodrow Wilson historians on exactly why that was. Of course there was precedent for it back to the Civil War in terms of going on an income basis. But I would also point out that it's not entirely true that we don't ever tax wealth in this country. For instance, I mean I'm sitting in a small office in my house. I pay a wealth tax, except we don't call it the wealth tax. We call it a property tax. And actually, that's even sort of worse because I end up like most homeowners, end up having to pay a property tax not based on my equity in the house because my wife and I are still paying off our mortgage. We're actually paying a property tax rate based on the top line figure, what is the assessed value of the house. Some states have automobile taxes and other sorts of property or asset based taxes. So even though we started the income tax system in 1913, it's not entirely the case that we strictly only have 100% income tax based system.

Anthony Scaramucci: (10:47)

So I'm with you intellectually on a lot of things. I'm not like one of these hedge funders that's anti-tax, I'm never moving to Miami. Love Miami, interviewed Mayor Francis, Mayor Francis Suarez on our show here, love Miami. One of my children lives in Miami, but I'm a New Yorker. I'm going to be here. I'm going to pay my taxes here. I'm going to do everything I can to help our city. And I'm a big believer that blue states, this is something that I argued with President Trump about when him and I had a relationship by removing the SALT deduction, you're misunderstanding what happens in these blue states. Philadelphia is a port city. New York, Boston, these are port cities. They're teeming with immigrants. Many of them are indigent. You need a welfare safety net, a safety net for these people. You also need to create a platform of equal opportunity for these people, despite the economic variances.

Anthony Scaramucci: (11:46)

And so I understand the need for all these things intellectually but I would make the argument, these great cities, in addition to the cities on the West Coast, the port cities drive the entire economy. So if you want to cripple or hamper those cities, what ends up happening is you create a negative effect on the rest of the country. And so this whole blue state red state divide, very damaging for the country. But I also think we have a bloated government, Brendan, and I think we have a explosive deficit. This would be an indictment of both parties for that matter. Let me give you the facts, you know them, 7 trillion from George Washington to George Bush, 22 trillion from Barack Obama to Joe Biden. And obviously there was an $8 trillion four year moment in there with Donald Trump. So how do we, I get it, I get the taxation issues, but how do we stop or contain the over promising of government and the lack of taxation, because all of this stuff is just either unfunded tax liability going forward, or we're going to devalue our currency and make it harder and harder for the people that you and I grew up with.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (12:55)

Yeah. So a couple things there, first just on immigrants. I'd poured out that contrary to what the expectations were, both New York City and Philadelphia grew much more than were expected. All the naysayers were saying they're either going to lose population or a stagnant growth. Census just came out and showed both ended up growing far more than was expected. And the reason was because of immigrants and immigration, which is no surprise. That's how both cities grew up. So it shows you, and by the way, how many times has New York been counted out in the history of what essentially in many ways is the capital of the world? New York is never dead. It will always come back. And I think the census figures were just the latest evidence of that. Now in terms of a deficit and debt, this was an interesting intellectual conversation that's happening right now, because admittedly, there is no, I'll be very frank, there is no political party that has a room or has much of a base for folks focusing on reducing the deficit and reducing the debt.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (14:16)

Donald Trump changed our politics in many ways. That's actually one underappreciated way in which he changed the Republican party. Now before, the Republican party would talk a big game, they would never live up to it on deficit and debt, but now they don't even really talk about it any more. And then of course, my party believes in government, believes in taking advantage of historic opportunities to do certain things on the social safety net. So the sort of rightly or wrongly the sort of Gerry Ford type republicanism is not there. Now what's interesting to me is, and you know, there's a school of thought out there saying, "Wait a minute, deficits." I mean, even Dick Cheney actually, when he was Vice President famously said, Deficits don't matter."

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (15:03)

There's an economic school of thought out there that that is talking about that as long as people in the world continue to have such full faith in the assets in the United States and our economy and are continuing to buy our bonds as a kind of a fleet of safety, and we continue to have interest rates as low as they are, I don't think you were going to see either side really talk much about deficit and debt. What I think it will take is any sort of, and I'm not cheering for this by any means, but I think what it would take is a dramatic increase in our interest rates for then one or both parties to finally be talking about this in a meaningful way.

Anthony Scaramucci: (15:53)

And listen, I respect all of that as well. And we had Stephanie Kelton on, Modern Monetary Theory. She wrote a great book about this, and I'm worried though, I have to confess this because I'm trained as an economist and I grew up in a blue collar neighborhood and I can prove empirically to Stephanie or you, Congressman or Senator Warren that when we create deficit spending, there is a benefit to it and there's a good modulation theory. I have elements of Keynesian thought in my personality, but we've got to be very, very careful about dollar devaluation because people that own the assets, they will get richer and richer as we're devaluing, but the middle and lower class, the wages don't catch up. And so I'll give you this example. My dad was a crane operator. I priced his wages, contemporaries them. He would be down 26.5% in real economic terms.

Anthony Scaramucci: (16:54)

So even though the wages did creep up over 35 years, the purchasing power is nowhere near where we were as children. My family would have gone from what I would call blue collar aspirational economics to blue collar desperational economics. And a lot of this is a result of this sort of a money corrupting, if you will, okay, where they are, but you want to tax the wealth. And I understand that, but I really want to just get my arms around the idea. So if I have, let's say $100 million, you tax it at the market rate, you tax it the way your property's taxed, where they're guessing at what it is. And they say, "Okay, you're going to pay this as an annual surcharge for the money that you've accumulated over your life.

Anthony Scaramucci: (17:43)

One argument would be though, "Wait a minute, Brendan or Congressman, I made the money. You paid me $1. I paid 50 cents to Bill de Blasio and Andrew Cuomo and Joe Biden. I got to keep 50 cents for myself. And then I invested that 50 cents and I happened to invest it quite wisely. I could have spent it. This is sort of a Prodigal Son dilemma from the new Testament, but I decided not to spend it." I would also say to you that it's not in my, the money's not in $100 bills in my swimming pool. It's being invested to create jobs and opportunity and innovation in the society. I'm delaying my own gratification in order to do that. And you're going to penalize me now. Again, I already got taxed on the front end, income based tax, made the money, paid my tax. I've now got it in savings. You're going to tax me again. And you say, "Yes, it's appropriate to do that because."

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (18:41)

Yeah. So a couple of things on mechanics. Our system would be similar to the four European countries that currently do this. It would also be similar to the sort of system we already have now at death, what we call the estate tax, or sometimes Republicans mislabel the death tax. We already had that infrastructure in place. So we're not, again this is not something where we're talking about creating something that doesn't already by and large exist, except instead of it being a one-time event at death, we're talking about doing it in an annualized way, although at a significantly lower rate. We're talking about 2 cents on every $1 above a $50 million exemption. Frankly, I mean the kind of folks that you know, who might have wealth more than $50 million, even if this were to happen, all of them would be wealthier year after year, even if they were to pay this, there's not one of them who's making a return of lower than 2% in any given year.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (19:51)

You also, you throw in there an assumption that we're increasingly seeing is not necessarily the case. And I mean, look, the argument on double taxation, I get it. In principle, that is correct. However, let's remember per what I was saying earlier, some of this wealth has actually never been taxed the first time. So that's in there too, right? I mean, that is one of the real flaws and whether it's the ProPublica articles or other sort of public reporting that we've been seeing, there are a number of ways in which the system is being gamed to evade that taxation.

Anthony Scaramucci: (20:30)

Let me stop you for our listeners to explain that, because I think it's a very interesting point. It hasn't been taxed because it was in what? Stock or property that got started and that value was created from, is that what you're saying?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (20:45)

I mean, I'm sorry, what I'm alluding to is ProPublica has done a series of exposes over the last several months. I don't know how they've gotten this information to be clear, but they have done remarkable reporting on a number of very wealthy individuals. Jeff Bezos is one of them, but folks who have been getting away with paying a zero tax bill, and for the most part, it seems legally. We're not talking about someone making 40,000 in tips and writing down 10,000. I mean, we're talking about legally gaming the system so that they have zero tax bill. And so when I tell you, look, if you go around Northeast Philly where I'm from, or parts of Queens in New York, and you talk to folks who are like the people, like our families are that we grew up with, they have a rock solid belief, whether Democrat or Republican, they say, "You know what? I know the system is screwing me. I know the guy who's in the very, forget top 1%, the top one half of one 10th of 1%. I know he's getting away with bloody murder and not paying anything. Meanwhile, here I am paying federal income tax. It's all being withheld from my paycheck, FICA, state, local. I'm getting taxed the wazoo. And yet the really big guys are getting away with paying basically nothing."

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (22:18)

As long as that exists, not only is that unfair economically, and we're missing a lot of tax revenue, it feeds the sort of cynicism that we're seeing about government. And you kind of referenced earlier and I think is major problem that we're facing in society, the sort of cynicism that we're seeing, the declining belief in the American dream, all of that goes into what we're talking about with what seems like trust the dollars and cents conversation is not. It's actually bigger than just the money.

Anthony Scaramucci: (22:53)

Okay. We're going to move on, I could talk all day to you, Brendan, so good Congressman Boyle. I appreciate it. So we can move on. I'm just asking these questions because we both know tax policy influences behavior, which does have an effect on the economy. And again, I'm not suggesting that we don't have issues in the tax policy and that there's been rank unfairness that needs to be addressed. I just want to do it in a way that obviously promotes growth in the society. So we're going to go rapid fire on a couple of other things, if you don't mind, okay? Let's go to gun control, too many special interests to do anything on gun reform and gun control to stop this sort of, this mutilation of our children?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (23:36)

Yeah, it's sickening. Generally, over the last five years, 10 years, 20 years, you see anywhere from 70 to 90, depending on the measure that is being questioned in the poll, you generally see somewhere between 70% and 90% of the American people who support some sort of gun control, whether it's background checks, whether it's a bit more aggressive than that, like banning the AR-15. Along that spectrum though, again, very solid majority support. And yet it hasn't happened and it hasn't happened because that one third that disagrees, historically that has been their number one big issue, and they have voted on it. I mean, there's a difference between preference and intensity, right? So the two thirds to 90% of people who might want gun control care about a whole host of other issues, but that one third or even less that cares about gun rights is so hardcore.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (24:37)

They'll take that NRA list to the polls with them in a Republican primary and vote strictly on that issue. Now what's interesting is that in 2018, after mass shooting after mass shooting, it's really the first time in our lifetime that I saw the politics of that change, especially in suburban America. So in the suburbs of Philadelphia, in suburbs in New York, suburbs of Chicago, you saw Republican members losing their seats, both for Congress, but also state legislative seats. And they were getting hit on the gun issue. The gun safety side or gun control side was really bringing up this issue in an offensive way, not a defensive way. So that leaves me optimistic that we will finally join the rest of the civilized world in having some sort of stronger gun measures. I do for the first, and it's funny, we do this interview before the last few years, I would have been really pessimistic on this question about whether or not I would see things change. The last couple of years, first time you've actually seen the politics of that now flip.

Anthony Scaramucci: (25:50)

Okay. So but I guess what I'm getting at is 70% of the country, maybe more would like some type of reform, but we've got these special interests creating these blockages [inaudible 00:26:03] and the procedures in the Senate and what they end up doing as well.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (26:11)

Yeah. So I mean, when this, like a lot of issues, this gets back to the F word, filibuster, because Manchin Toomey, when he pushed that, when they both pushed that, one is a Republican senator from my state, the other a Democratic senator from neighboring West Virginia, when they pushed that, I think they got 57 votes, but because of the filibuster, the 57 lost and the low 40s carried the day. I think we passed out of the House universal background checks and some other measures. In the Senate, that would have majority support. Every Democrat and I think anywhere from five to seven Republican senator supporting it, depending on the specific measure. But again, that's one of a whole host of issues that the question is, "Okay, what are you really going to do about the filibuster?" And if you keep the filibuster exactly as it is, it's hard for me, unfortunately, to see a meaningful change in our gun laws happen between now and the end of this session of Congress.

Anthony Scaramucci: (27:18)

All right, we're going to whip through, infrastructure bill. You like it, you don't like it?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (27:25)

Love it, love it. This is something that I had been pushing for a long time. Coming from an older state, we would benefit from it more than most places, and pretty much if you're anywhere in the Northeast, that's the case. And I actually, something I was totally wrong about, I did an interview on CNN, maybe a few days after the presidential election in 2016. And yeah, I was very vocally anti-Trump. And so the interviewer said, "Well, look, you're a Democratic congressman. Sounds like you won't agree with Trump on anything. Can you name one thing then that you could see agreeing with him on and voting for?" I immediately said infrastructure. And the part that I was wrong is my prediction was given the kind of campaign he had run in 2016 because economically, he was the first Republican since before Reagan who took some very uncharacteristic positions.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (28:19)

And frankly, I think that was one of the reasons why he won in 2016, whether he was talking about on entitlements, the way he was talking about infrastructure. I mean, if you remember, you're part of the campaign, Trump brilliantly in 2016 would campaign in Pennsylvania, ripping Hillary for not being pro spending on infrastructure enough. It was a completely uncharacteristic critique from a Republican candidate. So my prediction was that he would lead off with infrastructure. I said then there were a number of Democrats who work well with organized labor who come from areas that really want those jobs. There are a number of us who despite the fact we might oppose Trump on X, Y, and Z, we would work with him and vote for it. And why in the end he didn't do that, I think was one of his worst political mistakes.

Anthony Scaramucci: (29:16)

Well, I mean, one of the reasons is Paul Ryan and Reince Preibus and those guys convinced him otherwise, but his instincts were to go in that direction. Are you vaccinated?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (29:28)

I am. Yeah, I was fortunate to be among the first. I actually got my second, I have the Pfizer shot. I got my second shot about 24 hours after the Capitol insurrection. I would not recommend doing that when you haven't had sleep for the previous 48 hours. But that said, I thank God I'm vaccinated. My wife is, and we both have a seven-year-old who of course is not vaccinated. So we're two of the parents who are just really candidly, very nervous about the start of school.

Anthony Scaramucci: (30:04)

You say, lots of misinformation out there about the vaccine. I know perhaps you may not be able to opine about this, and if you can, I'm just looking for an opinion, the FDA, should the FDA approved the vaccine? Do you think there should be vaccine mandates in the country?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (30:26)

Yeah, I do, flat out. Vaccine mandates aren't anything new. Certainly, when we went to school and the college, we had a whole host of vaccinations.

Anthony Scaramucci: (30:38)

Your seven year old has a vaccination record, and he needs that vaccination record to cross into the school he's about to enter in September.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (30:46)

Yeah, but this is, you talked way back in the beginning, you talked about Facebook. This is a way in which I grew up in the '80s and frankly, there wasn't much difference in the way I consumed media as a kid in the '80s and say, folks growing up in the '50s and '60s did, right? You had the three big networks, forget FOX News.

Anthony Scaramucci: (31:08)

I was because I grew up in the '60s. Okay. Don't pick on us, Brendan.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (31:13)

Oh, you're a good bit older than I was. So you're a little bit like me. People think you're a lot younger, I take it than maybe the chronological, [inaudible 00:31:22].

Anthony Scaramucci: (31:21)

If I've got to go full Joan Rivers on you before this interview is over, I will. I want to make sure you know that.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (31:30)

But what I was going to say is that the reason why I bring this up is because this is a great way in which the change in the way we consume media is really influencing this tragic debate about vaccinations and all these kind of crazy conspiracies. Because if you grew up in '50, '60 '70s, '80s, there were three big networks. Basically all of us, whether Democrat or Republican consumed our media the same way, three big networks, a couple of newspapers in your town, same radio stations, but beginning with cable news in the '90s, and then the internet in the latter part of the '90s once it went widespread, that enabled, and then social media in around 2005 with Facebook, now we're in this very different environment in which we have self-selected news. And so, I have a close friend who's able to go on Facebook and is reading articles with all sorts of nonsense about what's in the vaccine. Previous era, that sort of misinformation would not have been able to be spread in the same way. And that's very dangerous.

Anthony Scaramucci: (32:49)

Yeah. A couple of my close friends, Jonathan Greenblatt for the Jewish Defense League and Kevin O'Leary debated whether or not the Taliban should be allowed on Twitter. What are your thoughts about that?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (33:04)

It's interesting. Well first, I haven't specifically thought of that aspect, but my view, and this kind of is similar to some others. If you're using a social media platform to inspire violence or cause violence, you don't have some inherent right to use that platform.

Anthony Scaramucci: (33:29)

Okay, you and I are probably closer, and I'm not with you, to be candid on the wealth tax only because that money, I think is somewhat misunderstood in the society. It's in the society working to create jobs. I understand that people think there's an unfairness. We have to rectify the unfairness and there's ways to do it. I'm just not exactly sure how to do it, but you and me are in total agreement on this. I mean, we didn't have World War II Nazi propaganda videos being shown in our movie theaters. Do they have a right to have those things shown?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (34:05)

Yeah, I think people are fundamentally, in the U.S. are fundamentally misunderstanding what the First Amendment means and what civil liberties mean. And if we were having this conversation 20 years ago, I was probably then a lot more optimistic about the internet and well, God, social media didn't even exist yet. We didn't have that term, but basically everything that the internet could do and unlock. A couple of decades later, when I see the effect that's had on our society, the impact that's had on our democracy, I'm a lot less positive today than I was a couple decades ago on that.

Anthony Scaramucci: (34:50)

Okay, we're going to let you go in a second here, but I want to talk about the bipartisan legislation, which is known as the U.S. Innovation and Competition Act. It's a five-year, $250 billion plan to help America compete with China on high-tech infrastructure. I think it's one of the more fabulous bills that I've seen in the last five years. And so did you vote yes on that bill? I'm assuming you did.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (35:15)

I'm a strong supporter of that, and I'll say this positively. I do think that one of the rare areas of bipartisan consensus is all of us recognizing frankly just how evil the Chinese regime is. It is not like the rest of us, and that's not a reflection on the people, frankly. They suffer from it more than anyone else, but we really need to wake up. I mean, the idea there now, there had been a school of thought maybe 20, 30 years ago that well, once China opens up economically, once they enact market reforms, democracy will naturally follow. That has flat out not happened. In fact, in some ways it's been the opposite. You have U.S. stars, NBA stars, movie stars that are now feeling muzzled by the Chinese government and the sort of economic power that they have. So I'm glad to see both parties getting tougher on China, getting tougher when it comes to competing against them economically, recognizing that they are not our friend. And so this is one of a number of initiatives that are within that vein.

Anthony Scaramucci: (36:31)

So the democracy is my final couple of series of questions. You worried about our democracy, sir?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (36:40)

Yeah. By nature, I'm an optimist. So my gut instinct is to say no, and it is to preach positively and evangelize about America, but I got to be honest, I am. And I mean, part of it is because of what I referenced earlier about the self-selected way in which all of us are consuming our news, and not even on the same basic fact sheet. Something like January 6th, I never imagined I would ever see something like that in the United States of America. So I don't know how anyone could go through the last several years, and especially January 6th and be more optimistic about the state of our democracy. I still have faith that we will get through it. We've gotten through previous eras before that looked very bad. So I'll still maintain that faith, but it is not without worry.

Anthony Scaramucci: (37:46)

My friend, I wish you the best. I know you're born on Ronald Reagan's birthday. He started out as a Democrat, if you'll recall. He ended up as a Republican. You seem like you're somewhere in the middle, so it's fascinating and it's a lot of fun to talk to you. I hope we get a chance to meet in person. Maybe we'll get you at one of our events someday when the Congress isn't in session, or maybe I can get down to Philly and have a surprise beer with you.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (38:13)

Yeah. I would love that. And whether it's the in-person SALT Talks or an Eagles-Giants game, one way or the other, I look forward to getting together with you.

Anthony Scaramucci: (38:23)

I just got to, I'm a lifelong Jets fan.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (38:26)

That's a lot better, okay. All right.

Anthony Scaramucci: (38:28)

I'm in permanent pain. You have a Philly native by the name of HR McMaster, General McMaster and I are close personal friends. We were arguing out with Governor Christie the other night at dinner, basically Christie's a Dallas Cowboy fan from New Jersey. What the hell is that?

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (38:44)

It's incredible. I saw Christie on Amtrak once. I was commuting to DC, introduced myself to him. And I said, "You might think the reason why I so strongly oppose you is because I'm a Democrat. It's because I'm an Eagles fan. How the hell are you a Cowboys fan? And especially coming from New Jersey."

Anthony Scaramucci: (39:03)

Yeah. I mean, it's one thing. Yeah it's one thing, if you're like a Giants fan, you can respect it as a Philadelphian. I understand that, but look, I'm a Met, Jet fan. So once in a while in that Catholic church say a prayer for your friend, Anthony. It's been a brutal 50 years. Let's just put it that way.

Rep. Brendan Boyle: (39:21)

You know, as a Philly sports fan, I can feel your pain.

Anthony Scaramucci: (39:24)

You be well. I really enjoyed our conversation. I appreciate you joining SALT Talks.

John Darsie: (39:31)

Thank you, everybody for tuning in to today's SALT Talk with Congressman Brendan F. Boyle, representing the city of Philadelphia in the United States Congress. Just a reminder, if you missed any part of this talk or any of our previous SALT Talks, you can access them on our website on demand at salt.org/talks or on our YouTube channel, which is called SALTtube. On our website, we also have full transcriptions and links to our podcast version of these videos as well. Please spread the word about these SALT Talks. We love educating people on a lot of the issues that Congressman Boyle spoke about today. We think he's a great representative for our country in Congress. So please tell your friends about these SALT Talks and follow us on social media. Twitter is where we're most active @SALTconference on Twitter, but we're also on LinkedIn, Instagram and Facebook, and on behalf of Anthony and the entire SALT Team, this is John Darsie signing off from SALT Talks for today. We hope to see you back here again soon.