America’s Place in the World: National Security & Leading From the Front with General John Kelly, Retired U.S. Marine Corps General & 28th White House Chief of Staff. General H.R. Mcmaster, Retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General & 26th United States National Security Advisor. Michele Flournoy, Co-Founder & Managing Partner, WestExec Advisors. Richard Fontaine, Chief Executive Officer, Center for a New American Security.

Moderated by Zoe Weinberg, Fellow, Schmidt Futures.

SPEAKERS

Michèle Flournoy

Co-Founder & Managing Partner

WestExec Advisors

Richard Fontaine

Chief Executive Officer

Center for a New American Security (CNAS)

GeneralJohn Kelly

Retired U.S. Marine Corps General & 28th White House Chief of Staff

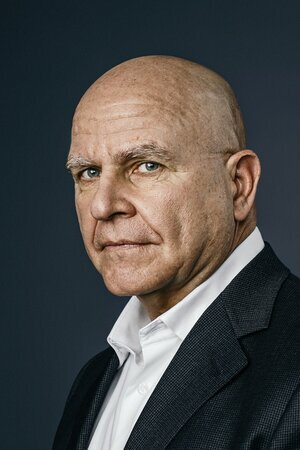

General H.R. McMaster

Retired U.S. Army Lieutenant General & 26th United States National Security Advisor

MODERATOR

Zoe Weinberg

Fellow

Schmidt Futures

TIMESTAMPS

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Zoe Weinberg: (00:07)

Morning. Thank you, SALT, for bringing us together in person no less. I'm Zoe Weinberg, and I'm pleased to kick off this morning with the discussion about America's role in the world and the future of national security. We have with us today General John Kelly, former White House Chief of Staff and former Secretary of Homeland Security. We have General H.R. McMaster-

Gen. John Kelly: (00:31)

Wait a minute now. And also a retired Marine.

Zoe Weinberg: (00:33)

And also a retired Marine. Most importantly, we have General H.R. McMaster, who's currently a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, previously National Security Advisor, and also a retired US Army lieutenant general.

Zoe Weinberg: (00:52)

We have Michele Flournoy, who is the co-founder and managing partner of WestExec Advisors and formerly Undersecretary of Defense for Policy under President Obama. We have Richard Fontaine, CEO of the Center for a New American Security and former foreign policy advisor in both the Senate and the White House. Welcome.

Zoe Weinberg: (01:16)

I'd like to start where everybody's attention is focused right now: Afghanistan. Exactly one month ago, the Taliban entered Kabul and took control of the presidential palace. Of course, historians are going to be debating for many years our role in the country, but with the events still very fresh, what are the lessons learned from both our decades-long engagement in Afghanistan and from our withdrawal? General McMaster, I'd like to start with you.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (01:45)

Well, so thanks for the question. I mean I think it is important that we learn the right lessons from, I think, what is a catastrophe in Afghanistan. I think the first step in learning the right lessons is to stop pretending. I mean what we hear from Washington today about the situation in Afghanistan and the ramifications, the costs, and consequences is exactly the opposite of reality.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (02:09)

So we have to stop pretending that we didn't surrender to a terrorist organization. We have to stop pretending that a lost war has no consequences. We have to stop pretending that the Taliban is going to share power and be concerned about the opprobrium from the international community and modify its behavior. We have to stop pretending that the Taliban is not completely interconnected with al-Qaeda, the Haqqani network, and lots of other terrorist organizations.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (02:41)

We have to stop pretending that the consequences of this surrender to a terrorist organization and our precipitous retreat from Afghanistan will not have profound consequences in three areas. First, the humanitarian catastrophe, which is just beginning, just beginning.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (03:01)

With our withdrawal, we have created not only a humiliating scene that is reminiscent but worse than the withdrawal from Vietnam in 1975, where we're now on fast forward to a hostage crisis more like 1979 in Iran, that is orders of magnitude larger and is of our own creation, not only for obviously US citizens but also for Afghans who helped us and for the citizens of our allies and partners who were part of the coalition.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (03:33)

So that catastrophe is now just beginning, but that humanitarian catastrophe is related to the security catastrophe of a massive refugee crisis that also is a source of strength for jihadist terrorists who are, by the way, the enemies of all humanity. Those refugees will become a great recruiting pool for the 20 or so US-designated terrorist organizations that are in the border area between Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (04:00)

We know from 9/11, we know from 20 years ago that when these terrorist control territory and populations and resources, they become orders of magnitude more dangerous. What's sad in the area of lessons is we didn't learn from 9/11 and we didn't learn from an even more proximate experience, which was our complete withdrawal in December 2011, when then Vice President Biden called President Obama and said, "Thank you for allowing me to end this goddamn war."

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (04:31)

Think about the conceit that underlies that approach to war. Wars do not end when one party disengages. While we have been developing policy based on the mantra of ending endless wars, we should at least acknowledge the agency and authorship over the future that our enemies have and recognize that jihadist terrorists are fighting an endless jihad against us. When we disengage from that problem set abroad, we can only deal with the consequences at an exorbitant price once that threat reaches our shores.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (05:03)

Then, finally, it's a political catastrophe, political catastrophe in connection with our credibility. Deterring conflict really, I mean, depends on capability times will. Our adversaries and enemies now think our will is zero. And so, this catastrophe is connected, I believe, and will be connected to more aggressive actions by the Chinese Communist Party. Just read the China Daily and what they're saying about Taiwan.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (05:31)

It is connected to the missile launches out of North Korea and the activity at young beyond. It'll be connected, I think, to more aggressive actions on the part of the Iranians as well. And so, we're in for a rough ride ahead, and it's going to be an even rough ride because I think we have demonstrated our inability to learn lessons from even this ongoing catastrophe.

Zoe Weinberg: (05:58)

Thank you. Richard, what's your take on lessons learned and what are the implications for our longer term role in the region?

Richard Fontaine: (06:04)

Well, I think one of them is the difficulty with which the United States has in solving some of these foreign policy challenges. Afghanistan's a good example. We constantly and continue to look for the solution. We're going to defeat the Taliban utterly, we're going to surge troops in, we're going to take them back, we're going to leave. Something is going to solve it.

Richard Fontaine: (06:31)

Iraq was a similar situation in 2011. Everything was about exit strategies, about solving a problem. Some of these problems can be mitigated. The threats of jihadist terrorism can be mitigated, but they're not going to be solved in any meaningful timeframe.

Richard Fontaine: (06:48)

That's not very conducive to our way of thinking where we're going to get in, we're going to accomplish something, and then we're going to get out. If we've been there for a long time, it must mean that we've done something very, very wrong and we need to stop it.

Richard Fontaine: (07:00)

What that tends to do in the Greater Middle East in terms of military operations is a yo-yo diet where we're on the ground with a certain number of forces, we're trying to do some things. Doesn't seem to quite work out. We go really big half-satisfying. Then we say, well, nothing's going to work so we come all the way down.

Richard Fontaine: (07:18)

Really what we need is sustainability, sustainability over a long period of time. We need staying strategies as much as we need exit strategies for some of these kinds of things. I think Afghanistan is a case in point where we had too few at the very beginning. Then we surged troops and we came down. Now we say, well, it can't be won.

Richard Fontaine: (07:37)

Well, in fact, our American presence was not going to topple ... It was not going to defeat the Taliban, but it was going to prevent the government from being defeated by the Taliban. Those are two very different outcomes from an American interest and American point of view.

Richard Fontaine: (07:55)

And so, to focus on sustainability and the mitigation of threats rather than all or nothing, in or out, solving the threats once and for all and then coming home once they're done, I think, is the main takeaway. But, in fact, I think we're probably going in the opposite direction right now.

Zoe Weinberg: (08:13)

General Kelly, both General McMaster and Richard have referred to the very real risk that Afghanistan may become a haven for terrorists. There's been reports that the Biden administration has considered, or allegedly is considering, cooperating with the Taliban to combat the ISIS affiliate on the ground. I'm curious, how should we think about the terrorism threaten the country and the trade-offs of possibly cooperating with the Taliban to reduce it?

Gen. John Kelly: (08:46)

Well, the first thing I'd say is the Taliban is a terrorist organization, as both these gentlemen have referenced. They're aligned with all of the other radical terrorists, Islamic terrorists. This war is not over in their minds. Just because we withdrew doesn't mean the war is over. We're still at war.

Gen. John Kelly: (09:07)

This war will not be over for a long, long time. It's not about our friendship with Israel. It's not about opportunity in the Middle East. It's about who we are as a people. Until we either surrender to them, and I mean more than just surrender like we did in Afghanistan, or we just simply defeat them over time.

Gen. John Kelly: (09:31)

So the war's not over. So the idea that you can deal with the Taliban, who are sworn radical terrorists, that have sworn to kill Americans and, frankly, anyone they can kill on the west, to say that you can work with them, well, maybe there are smarter people in the White House than I can imagine. I can't wait to watch it. But I just don't see it working.

Zoe Weinberg: (09:54)

On that note, Michele, where do we go from here?

Michele Flournoy: (09:59)

Well, I think the thing that makes this even more consequential is that it's happening at a time when we're really in a period of a strategic inflection point. We've had 20 years focused on the post-9/11 period fighting terrorism. The problem has not gone away. It still needs to be managed.

Michele Flournoy: (10:19)

But we have a new set of challenges, and particularly the rise of China as a great power, the continued presence of revisionist Russia under Vladimir Putin, who's constantly trying to undermine democracy in Europe and here.

Michele Flournoy: (10:37)

But we're in a new era where we are going to be in a major competition with a rising China that is very committed to changing the rules of the road, changing the rules for trade, changing the rules for use of force, imposing its will on smaller countries, changing the architecture and the whole feel and operation of the Indo-Pacific region, which, oh, by the way, is the most important part of the world when it comes to the prosperity of Americans and the security of Americans here at home.

Michele Flournoy: (11:09)

So this point where we've just mismanaged withdrawal, which these two gentlemen can confirm that one of the most dangerous parts of a military operation is coming out of it. But that's clearly been mismanaged. I think US credibility has taken a hit at exactly the moment where we need that credibility and we need that leadership to start rebuilding alliances and partnerships and to try to take on and deter any kind of conflict with China, constrain China's influence, and in certain areas like climate change and preventing the next pandemic, we've got to find ways to cooperate.

Michele Flournoy: (11:52)

So the world really needs US leadership right now. Even though I think the president sought to get out of Afghanistan wisely, or unwisely, to free up bandwidth and energy and focus and resources to put to the Indo-Pacific, the truth is this has created such a mess that it's actually draining that bandwidth and refocusing it on the Greater Middle East.

Michele Flournoy: (12:17)

So I am concerned. I think the administration has made its own job much harder going forward to really focus on the major challenges we have in Asia.

Zoe Weinberg: (12:28)

I want to stick with this for a second. I think you're right. In many ways, to a certain extent, we are closing the chapter on 20 years of very counterterrorism-focused operations and shifting our focus toward great power competition, and specifically competition with China, as you mentioned. Michele, I mean this is obviously a departure from the playbook of the early 2000s. Is the United States prepared to compete with China? If not, what needs to change?

Michele Flournoy: (13:00)

Well, I think we need a vision and a leadership engagement. I think we need to have a president to talk to the American people to say this is one of those moments that Americans need to stand up and do what we're really good at. We are good at standing up out of crisis, dusting ourselves off, coming back strong, whether it was the Great Depression or World War II or Vietnam. I mean you can go through the scenarios, the financial crisis.

Michele Flournoy: (13:28)

This is one of those moments where we've got to stand up, turn the corner on COVID, get the economy again, reinvest in the drivers of our own competitiveness, re-embrace our allies and partnerships, but with a purpose, that we are going to compete. We know how to compete when we're inspired to do that, and we need to do it economically, technologically, in terms of defending democracy, and militarily.

Michele Flournoy: (13:53)

I'll just comment on the military piece. We do have the greatest military in the world, but we can't rest on our laurels. We have to adapt, we have to transform, we have to innovate to be able to effectively show up and deter a country like China, which has spent the last two decades, while we were focused in the Middle East, investing in the capabilities to try to keep us out of the Indo-Pacific.

Michele Flournoy: (14:19)

So we have a lot of work to do. We have a lot of rebuilding of our diplomatic core and the ability to show up and shape things there. So if you ask me, "Would you rather have the Chinese hand cards to play or the American hand cards to play?" I would far prefer to have our hand cards, but we have to start playing those cards better if we're going to be successful.

Zoe Weinberg: (14:42)

Yeah. So our allies obviously play a meaningful role here. Richard, you've written about the need to unite democracies, to enhance digital cooperation through an alliance of techno democracies. Will you tell us a little bit more about that concept and the role of multilateralism more generally?

Richard Fontaine: (15:01)

Sure. So when you're talking about this grand US-China competition, it's natural to think, well, power is shifting in the Chinese's direct because they're becoming, every year, more powerful, richer, more militarily capable, more assertive, et cetera.

Richard Fontaine: (15:17)

The real way to think about it is not America on one side of the scale and China on the other, but China on one side of the scale and America and all of its allies and partners, like-minded countries on the other side of the scale. When you start to add up all the capabilities, the economy, the diplomatic weight, and everything, then you see quite what we have to work with in this grand competition of United States and China, and this contest of models, of autocracy and democracy, and things like that.

Richard Fontaine: (15:46)

Those are some of our greatest assets are our system of alliances, the like-minded nature of partners that want to work with us more than they did even in the past, frankly, some of their apprehensions about China and it's illiberal directions in which it's going.

Richard Fontaine: (16:03)

That then goes into, okay, so what are the new things that you do about this? You're starting to see whether it's on the military front, on the diplomatic front with the Quad, with the US, Australia, India, and Japan, new frameworks there that the Trump administration really revived and has now been taken up by this administration.

Richard Fontaine: (16:21)

So you're seeing these different kinds of ways of countries that are like-minded working together. One that has not really come to the fore yet, but in my mind and in minds of others really needs to, is on technology. So right now there are technology aspects to gatherings here and there of the G7 and the US and the EU and others.

Richard Fontaine: (16:44)

There's no forum, there's no group where you get like-minded democracies that are the advanced technological economies together to say what is it that we really care about in terms of our democratic practices, our economic matters? What are we worried about in terms of the use of illiberal technology, surveillance technologies, Chinese innovation, et cetera, et cetera, and how do we actually work together across lines, both private sector and government sector to do this?

Richard Fontaine: (17:16)

It's the kind of thing that when you start to think about it, I think you start to say, well, it's almost amazing we don't have something like that now, given that technology is so key to everyday life, but also to this grand competition that we're in. And so, to build a structure like that, where the like-minded techno democracies can cooperate, I think, is a pretty near-term imperative.

Zoe Weinberg: (17:38)

On the subject of technology, I want to step back for a second and consider the role of technology and the evolution of conflict over time. Some have argued that, increasingly, war is becoming less about kinetic combat on the ground and instead technological control, surveillance, cyber attacks, disinformation, stolen intellectual property. That is what's going to define the next era of war. General McMaster, do you agree with this assessment? What does that mean for militaries of the future?

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (18:11)

No, that's a pipe dream because those who say that, really, really, really the next war will be fundamentally different from all those that have gone before it because of X technology. In the '90s, it was the combination of surveillance technologies, assured communications, space-based assets, precision strike capabilities, and GPS and so forth. Remember, we're supposed to have a revolution in military affairs.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (18:38)

Future war would be fast, cheap, efficient, and waged from standoff range. But what this kind of thinking neglects is really there are two ways to fight wars, asymmetrically and stupidly. You hope your enemy picks stupidly like Saddam Hussein did in 1991. But I think a lot of countries and jihadist terrorist organizations learned vicariously from the ass-kicking of that army in 1991. That's why jihadist terrorists used box cutters and airplanes to bypass our technological military prowess and strike as asymmetrically.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (19:14)

We also keep thinking that really force on the ground, that doesn't make a difference anymore, right? Well, do you think it made a difference to the Taliban? I think it did. When people say, "Hey, there are no military solutions to these emerging problems," we know the Taliban had one in mind. What we don't think about is the need to integrate all elements of national power and efforts of like-minded partners to achieve well-defined objectives in war.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (19:43)

That's the essence of strategic competence. We are incompetent because we divorce these and we engage in strategic narcissism, essentially. We define the world as we would like it to be and assume that we can map out a linear course toward progress, the kind of wars we want to fight in the future, for example. We're going to invest in these fewer and fewer, more exquisite systems. Well, guess what? Hey, your adversaries have a say. They develop countermeasures.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (20:13)

And so, I would say that the element that is most important to thinking clearly about future war is to balance, change, technological change, with continuities in the nature of war. There are really four of those.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (20:26)

War is an extension of politics. So you fight to achieve sustainable political outcomes consistent with your interests, like a political order in Afghanistan that is fundamentally hostile to jihadist terrorism. That would've been a good outcome. Afghanistan, as Michele mentioned, didn't need to be Denmark. It just needed to be Afghanistan.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (20:45)

Second, war is human. People fight for the same reasons Thucydides identified 25, 20 years ago, fear, honor, and interest. What we hear these days is the secretary of state and others saying, "Gosh, it's not in the Taliban's interest to do X." Well, the supreme leader of the Taliban, Hibatullah Akhundzada, his 17-year-old son was a suicide bomber. What else do you really need to know? Emotions and ideology drive and constrain the other as well.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (21:12)

Third, war is uncertain. Again, the future course of events depends not just on what we do, but what on the other decides to do. Remember in 2009, 2010, when President Obama announced the reinforced security effort in Afghanistan. He announced the timeline for a withdrawal at the same time and then said to the Taliban, "Hey, let's negotiate." President Trump actually doubled down on that approach. I mean how does that work? That resulted in the capitulation agreement of February of 2020.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (21:44)

Then, finally, war is a contest of wills. What we hear a lot today, we hear, well, the Americans don't support the sustained effort in Afghanistan, even though it was at a very low level and relatively low risk as the Afghans bore the brunt of that fight and our European coalition members bore a lot of that fight as well. Well, it's not a surprise that Americans didn't support it because three presidents in a row told them it wasn't worth it.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (22:07)

So I think that we neglected our peril continuities in the nature of war. The historian Carl Becker said the memory of the past and anticipation of the future should walk hand-in-hand in a happy way. We engage in self-delusion when we think that really the next war will be fundamentally different from all those who've gone before it. Wars still resemble each other more than they resemble any other human activity.

Zoe Weinberg: (22:34)

General Kelly, I'd love to get your perspective on this. What are the ways in which defense strategy may need to evolve and what are the places where there ought to be continuity?

Gen. John Kelly: (22:45)

Well, the first thing is the United States, in its very unique role in the world, has got to be able to operate across the spectrum of warfare, from cyber and all the rest to out and out war. So that's the reality of it.

Gen. John Kelly: (22:59)

The strength of the US military, I would offer, before we even talk about technology and weapons and all that, are the people that are in it. Very unique people, very unique Americans. I would offer this in terms of continuity.

Gen. John Kelly: (23:16)

The first war I was told as a young guy that I needed to get involved in was the Vietnam War. I didn't go to Vietnam, but that's the war where we just had to get in there, had to stop communism. And so, an awful lot of people went in, 50-plus thousand killed.

Gen. John Kelly: (23:39)

Then around the late '60s, Washington lost interest in the war because, politically, it was not popular anymore. So we decided to, in my view, cut and run.

Gen. John Kelly: (23:52)

Then the next time, I was told that this was one of the most important things you could get involved in, young men, young women, was the Beirut effort. That was fine until a bomb went off and then, again, Washington lost interest in that.

Gen. John Kelly: (24:07)

Then the next one and the next one and the next one. So you go to 9/11, and this is the most important thing young men and women can do. We've got to go and we've got to fight terrorism in Iraq and Afghanistan. 20 years later, we lost interest in that.

Gen. John Kelly: (24:23)

When you start talking about conflict at the level, God forbid, with China and the potential casualties and how fast those casualties, again, I'm not so sure ... If I was a young person listening to we really have to shift to China and the Indo-Pacific and really do what we need to do out there, with the possibility of a war with someone like China, I'm not so sure ...

Gen. John Kelly: (24:49)

The consistency in terms of how we've treated wars since World War II is you've got to go in, you've got to do it, and we lose interest in it, mostly because it's politically unpopular. Then, of course, the politicians want to run for it.

Gen. John Kelly: (25:06)

So I really wonder if we ought to even consider the possibility of a conflict with China, because I just don't think we have the staying power. The troops do. They'll go and do anything that they're told to do to, to their lives. I'm not so sure, though, that that level of sacrifice can be maintained if there's a major war, clash, if you will, with China or for that matter Russia.

Zoe Weinberg: (25:46)

Any responses to that?

Michele Flournoy: (25:48)

Well, my own view is that the name of the game is deterrence, and our efforts have to be to make sure that the leaders in Beijing understand that if they launch aggression, they can't be successful, or they will face such costs from the international community that it's really not worth it, that they shouldn't take the action. They should try to work things politically and diplomatically and not through military means.

Michele Flournoy: (26:18)

But that means we've got to show up in the region, diplomatically. We have tons of embassies that are still empty, or at least ambassadorships. We've got to show up in every major forum there to reassure people that we care, we're here. We've got to find some positive agenda for engaging the region economically on trade.

Michele Flournoy: (26:41)

I think one of the biggest strategic mistakes that both Democratic and Republican administrations made was not joining the Trans-Pacific partnership, which is a trade deal that we negotiated and set the standards for, high standards. Then all of our allies joined and we didn't. I mean that's a self-inflicted wound.

Michele Flournoy: (27:03)

But we've got to show up and then we have to make the investments in the people and the technology and the concepts and demonstrate those concepts to make sure the Chinese understand that our military can inflict terrible costs if they try to move aggressively and unprovoked and against the rules of the road.

Michele Flournoy: (27:25)

So I'm not suggesting that we should charge into a war with a nuclear power, but I think it's in our interest to double down on trying to prevent that war in every way possible, but on our terms, on terms that favor the like-minded states and the democracies that Richard is talking about.

Michele Flournoy: (27:46)

This is a competition between systems. The stakes in this are are we going to have a global order that is defined by free market democracies? Are we going to have a global order that's defined by authoritarian states that are embracing a very oppressive surveillance-based model of governance? I think those stakes are pretty high.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (28:13)

Just to pick up on Michele's point, I think it's important to recognize that China has increased its defense measure by about 800% since the mid '90s. What's important is deterrence by denial, as what Michele's talking about, really. It really is convincing a potential enemy that the enemy cannot accomplish its objectives through the use of force.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (28:32)

I think it's important to invoke the early 20th century philosopher and theologian G.K. Chesterton, who said that war may not be the best way of settling differences, but it may be the only way to ensure they're not settled for you.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (28:47)

And so, it's important for us, I think, to maintain military capabilities that are essential to deterrence by denial, but also capabilities that will allow us to protect our vital interests and our security against determined enemies, from jihadist terrorists to the Chinese Communist Party, if they were going to employ military force against us.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (29:12)

I don't think the defense budget today, for example, is adequate to do that. I think Teddy Roosevelt's old adage of "speak softly and carry a big stick". On China, we're speaking super loudly right now and we're carrying a stick that's growing smaller because of real reductions in the defense budget.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (29:32)

So I think this should be more of a topic for public discourse these days as well. How do we maintain our deterrent capability, especially given the increasingly aggressive nature of the Chinese Communist Party that we've seen just in the last couple of years, bludgeoning Indian soldiers to death on the Himalayan frontier, weaponizing islands in the South China Sea, ramming and sinking Vietnamese vessels, the constant overflights and aggression toward Taiwan, this announcement the other day that they might start to patrol Taiwanese airspace with People's Liberation Army Air Force aircraft?

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (30:07)

I mean this is a period of extreme danger, I think. The only way to, I think, prevent the worst from happening is, as Michele says, to be strong in the region and to be strong with allies and partners.

Richard Fontaine: (30:19)

We also-

Gen. John Kelly: (30:20)

The other-

Richard Fontaine: (30:20)

I was going to say I think we obviously have to be intently concerned with deterrents, by bolstering deterrents, being prepared to win a war if, God forbid, everyone came, so that we can hopefully avoid it at all costs. That's with respect to China or Russia or some of these other threats. But we also have to look at the non-military threats that these countries pose that we need to defend ourselves against, and the much higher likelihood that we're going to face those.

Richard Fontaine: (30:49)

So, for example, we've got an entire NATO alliance that thinks every day about what we would do if a Russian tank column moved into Estonia and how we would beat it back. That's entirely appropriate. But NATO doesn't look at protection of our own democracies against Russia's meddling in democratic practices through cyber means, as they did in the United States in 2016 and in 2020, as they did in France before their presidential election, as they've done in Britain, as they do in other countries. And yet the possibility that that's going to happen is 100% because it's happening right now.

Richard Fontaine: (31:24)

Same thing on China. We have to think about what it would look like if China acted in an aggressive way militarily against one of our allies in the region and what we would do in response to that, entirely appropriate.

Richard Fontaine: (31:36)

But we also have to be thinking at the much higher likelihood they'll engage in the things they already do, like theft of intellectual property through cyber means at vast scale, at surveilling people well beyond their borders and trying to impose their own value system on other countries and their technological governance matters and things like that, their economic dominance and their use of economic coercion to try to get the outcomes that they like, including with countries like Australia and things like that.

Richard Fontaine: (32:06)

And so, we can't leave behind all of the non-military stuff that's happening right now while we prepare for a war that we hope never happens.

Zoe Weinberg: (32:15)

I want to shift gears and talk a little bit about our economic agenda as it relates to national security. This is obviously relevant to China, but extends beyond our engagement there. There's been a lot of activity when it comes to a defensive economic strategy, export control, CFIUS, Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, sanctions. But there's been little, it seems, on the other side of the ledger when it comes to advancing a positive economic agenda. Richard, what do you think we should expect when it comes to proactive economic measures?

Richard Fontaine: (32:49)

Not much in the near term because it's caught up in domestic politics, but it's a real missing piece. I mean Michele mentioned the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Take Asia, for example. There are two region-wide, big trade agreements in Asia. There's TPR, CPTPP now, and there's RCEP, which is the other one. The United States is party to neither of those. China's party to one and is closer to joining TPP that we are at this point.

Richard Fontaine: (33:21)

There's been talk about digital economy agreements. Well, we can't. Trade is too controversial now. We're in this protectionist mindset. But maybe we can get digital economy agreements that liberalize digital trade and show some leadership there, reduce the barriers, and things like that. But there's been no effort thus far out of the administration, and the Congress is not particularly pushing this very hard.

Richard Fontaine: (33:44)

So I think you're absolutely right. There's all kinds of defensive measures on how to deal with export controls and investment screening and all these other things. Virtually nothing on the positive side of what would economic leadership in various parts of world look like, not only for geopolitical reasons but for no-kidding economic reasons at home.

Richard Fontaine: (34:05)

But it's too domestically, politically difficult now. Maybe something after the midterms or in a second term, but we're now seeing more or less three administrations in a row that are not terribly gungho on the positive economic side. And TPP didn't pass, as we know.

Zoe Weinberg: (34:29)

Yeah, Michele?

Michele Flournoy: (34:30)

If I could just jump in. I think there is an opportunity to make some lemonade out of lemons. When you look at the incredible integration of our supply chains globally with China, there are areas where, fine, not a big worry, but there are areas that touch on national security, that touch on our digital economy, that touch on heightened awareness, public health, supply chains, and pharma supply chains.

Michele Flournoy: (35:02)

There are places where we really need to reconsider our vulnerabilities and develop much greater resilience. Some of that may be reshoring things to the United States, but in many, many cases, it's going to be redistributing supply chains in the region.

Michele Flournoy: (35:21)

That's an opportunity for us, in terms of absent the trade agreement we wish we had, to make at least some progress in bolstering the economies of some of our key partners by moving some of the supply chains that are currently in China to places like Vietnam, or pick your favorite ASEAN economy.

Michele Flournoy: (35:44)

So I do think there's an opportunity there. But in the meantime, to me, the most important thing we can do economically is actually invest in the drivers of our own competitiveness here at home, which science and technology spending, research and development spending, access to higher education, 21st century infrastructure.

Michele Flournoy: (36:04)

Smart immigration policy. I mean look at the founders of Silicon Valley. Half of them are either immigrants or first-generation Americans. We benefit from an immigration policy that welcomes and draws the best and brightest from around the world to this country and then convinces them to stay and make their businesses here and so forth. We've lost the bubble on that somehow in the last administration and the last few years.

Michele Flournoy: (36:30)

So this is, this is an agenda that I think resonates in a post-COVID America. I think it's very, very important. As we evaluate these big investment bills, the two infrastructure bills, the Chips Act, we've got to make sure that we're investing in replacing some big bets in the areas where we need to compete. We're not just investing in technology, but we're investing in the human capital that's really going to help us win the competition in the longer term.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (37:04)

I would just say that economic security is national security. I think just one area I'd like to highlight is an area of energy security, how that relates to carbon emissions and climate change.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (37:13)

I think because we don't look at the interconnected nature of energy security and national security that we make some bad decisions. I mean the Biden administration blocked the Keystone pipeline, which made a lot of sense in terms of protecting the environment and from an energy security perspective and then green-lighted a Russian pipeline that has profound implications for Russia and Russia's ability to have course of power over Europe.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (37:39)

And so, I think we have to look at the interconnected nature of these problems and make decisions based on informed judgments, and ensure in the area of energy in particular that we don't trade our dependence on Middle Eastern oil in the 1970s for a new dependence on fragile supply chains that are dominated and controlled by China as we shift to the next-generation energy sources. In particular, I'm thinking of supply chains related to rare earths and rare earths refinement, battery manufacturing, and so forth.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (38:10)

So we have a lot of work to do, I think, from an economic security perspective, resiliency of supply chains that became too fragile based on maybe unchecked globalization or a bias in favor of efficiency rather than resilience.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (38:27)

We have a lot of work to do to catch up to China's weaponizing its authoritarian, mercantilist model against us. This is in areas like the Endless Frontier Act, the Chips Act, which are elements of industrial policy, which we don't do particularly well and have to be careful about, but I think are necessary to compete with China's economic aggression.

Zoe Weinberg: (38:49)

We only have a few minutes left, but I want to touch briefly on one more topic that's generating a lot of headlines these days, and that's space. Of course, historically, space has obviously been the domain of the federal government and programs in defense and science. But now we're watching the competition between Blue Origin and SpaceX and Virgin Galactic play out in real time.

Zoe Weinberg: (39:11)

Michele, you recently joined the board of Astra Space. What do you make of the commercialization of space and where is it headed?

Michele Flournoy: (39:21)

Well, I think it is a new frontier and it's a very exciting time. Because I think there's a lot that we can do in space to actually help better manage the planet, particularly when it comes to things like climate change, resource depletion, environmental degradation, and so forth.

Michele Flournoy: (39:42)

But it's also a great example where the federal government changed the model and opened the doors to commercial industry with great benefit. I mean the credit goes here to NASA, which decided to open up the door, let commercial industry compete with the traditional defense industry in providing solutions in space.

Michele Flournoy: (40:04)

It really created a market. Now we have not only the space companies you've heard of, but some of the ones you haven't heard of yet that are coming up with very interesting new models.

Michele Flournoy: (40:17)

Since you mentioned Astra, I mean Astra's model is to get to daily launch on demand out of a container truck from anywhere in the world. They're mass producing high-quality rockets that can put payloads for commercial, defense, intelligence into bespoke orbits and beat the best competitors on price.

Michele Flournoy: (40:39)

When you talk about resilience, when you talk about space becoming a contested domain and needing to be able to put assets back into space so we're not blinded, so our GPS doesn't go down, so our communications doesn't go down, et cetera, anything that contributes to that resilience has got to be part of our future.

Michele Flournoy: (41:00)

So this is one of those areas where I think it's a very exciting time, because you've got a lot of new entrants, a lot of new ideas, and some real energy behind transforming that sector.

Zoe Weinberg: (41:09)

General Kelly, I know that you departed the administration before this Space Force was created. But I was wondering if you could tell us anything about the motivation for its creation and what we can expect from the Space Force?

Gen. John Kelly: (41:23)

Well, there were a lot of people that had been encouraging this move for some time. The United States Air Force was doing, to say the least, a good job in terms of managing assets in space and that kind of thing. But there were certainly people that came on board that argued that it's about time to break it out separately.

Gen. John Kelly: (41:46)

So it wasn't necessarily ... And I don't know, H.R., if you remember. I mean there were a lot of good ideas coming into the White House, but it was not necessarily the president or someone like that who decided we've got to do Space Force. There was a lot of discussion about, okay, well, do we really need it now or do we need it at all? Because the Air Force has a separate Space Force and why aren't they doing a good job and all of that.

Gen. John Kelly: (42:09)

But I think, at the end of the day, it's a good decision. It's not going to grow into a huge organization nor does it need to. I was just up in strategic command up in Omaha last week and the week before, frankly, and a lot of great work being done on the Space Force. They're already credible and they'll get even more so.

Zoe Weinberg: (42:33)

Any final thoughts? Yeah?

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (42:34)

Yeah. I'll just say sometimes the government puts the right person in the right job. I think General Raymond and then his deputy Bill Liquori, who was our director of defense and worked with the Vice President in the space council to develop, I think, a really sound space strategy that ought to have broad, enduring, bipartisan support going into the future. There's an unclassified version and then there's a classified version. I think it's actually quite good.

Gen. H.R. McMaster: (42:57)

I was agnostic on it, but now that it's done, I think it was the right decision to split out the Space Force, because we've got the right people working on, as Michele just mentioned, is ... We're late to the game, recognized as a contested domain. There's so much potential now thanks to really the private sector coming up with so many innovative solutions to the problems we have and the opportunities that we have in space.

Zoe Weinberg: (43:24)

I have-

Richard Fontaine: (43:25)

The-

Zoe Weinberg: (43:25)

Go ahead, Richard.

Richard Fontaine: (43:26)

The one thing I would add is I think the commercialization, the creativity that's been unleashed in this country around space is a good example of the bright side of some of the darkness that we were talking about on this panel, because when you're talking national security, you talk about threats and China and Afghanistan, and it starts to get pessimistic.

Richard Fontaine: (43:47)

I think it's a good example because everything that the United States needs to compete in this new world that we're entering, whether it's China or deal with the threats around the world, we already have. We have the strongest, most powerful, richest, most creative, most innovative country in the world with an attractive democratic system, lots of friends around the world. It's about putting those pieces together and drawing on our greatest strengths as Americans that's going to win across this whole swath of stuff.

Richard Fontaine: (44:19)

On the one hand, it's daunting when you spend most of your hour talking about all of the threats and all the problems in the world, but the encouraging side is, as Americans, we're in the lucky place of if we just are better versions of ourselves, then we'll be able to deal adequately, if not excellently, across the whole spectrum of them.

Zoe Weinberg: (44:40)

Richard, thank you for helping us to end on a positive note. I have one final question this morning. This was a special request. I won't say from whom. It's for General Kelly. You can answer in just a sentence or less. General, tell us what was it like to fire Anthony Scaramucci?

Gen. John Kelly: (44:59)

Well, of all of the things I did at the White House, it was certainly the most enjoyable thing.

Zoe Weinberg: (45:02)

Great. Well, thank you.