Raghu is the Co-founder and CEO of FalconX, one of the largest and fastest growing digital asset brokerages.

Steve Kokinos: The Future of Finance | SALT Talks #265

Afsaneh Beschloss: Where Is Inflation Heading? | SALT Talks #264

Avik Roy: Bitcoin & the U.S. Fiscal Reckoning | SALT Talks #263

Joshua Frank: The State of the Crypto Markets | SALT Talks #262

Jeremy Allaire: Internet Money | SALT Talks #261

Bitcoin for Billions: Building the Lightning Network with Elizabeth Stark | #SALTNY

Bitcoin for Billions: Building the Lightning Network with Elizabeth Stark, Chief Executive Officer & Co-Founder, Lightning Labs.

Moderated by Brett Messing, Partner, President & Chief Operating Officer, SkyBridge.

MODERATOR

SPEAKER

Elizabeth Stark

Chief Executive Officer & Co-Founder

Lightning Labs

Brett Messing

Partner, President & Chief Operating Officer

SkyBridge

TIMESTAMPS

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Brett Messing: (00:07)

Well a year ago I was working out on a Peloton because it was a pandemic. And I was studying about Bitcoin because it was a pandemic. And I was listening to a podcast by Peter McCormack about the Lightning Network and I was blown away and I got off the podcast and I called Ross Stevens of NYDIG, our sponsor. And I said, can they really do that? Because if they can really do that, this is so much bigger than I realize. And he said, they can do that. You have to speak to Elizabeth Stark. So here we are. What is the Lightning Network? No E by the way, Lightning without an E. And why is it important?

Elizabeth Stark: (00:50)

Thanks, Brett. First of all, it's so incredible to be here today as a New Yorker with this crowd here, being in the financial center of the world and one of the tech centers of the world. So, Ross is correct. This is possible. And the Lightning Network is a technology that enables instant high volume transactions over Bitcoin. You can think of it as kind of this second layer as we call it or a transaction layer operating on top of the Bitcoin blockchain. So today on the internet, and by the way, I'm a tech geek. I come from the land of magic internet money as we say in the Bitcoin world. Today on the internet, it's really easy to send a photo in any application to somebody anywhere around the world instantly, right? You can do it in text message. You can send it via Twitter, WhatsApp, in a variety of ways. But why can't you send value?

Elizabeth Stark: (01:46)

So being the internet geek that I am, in the early days of the internet I wondered why can't you actually just send money? For example, I love music, to a musician, to a band, to a DJ, to somebody that created a video and just embed it natively in the internet. So the goal with Lightning is to be able to natively embed value and payments in the internet. In fact, the early creators of the internet, Tim Berners-Lee, in the early nineties envisioned that this would be the case back then. They created an error code it's called HTTP 402 payment required, which is kind of like 404 not found, it just was too early.

Elizabeth Stark: (02:21)

So when I learned about Bitcoin, I thought, this is really cool. You know, will this actually scale? And will people be able to use it to natively embed payments on the internet? And then I learned about the possibility of this second layer operating on top of Bitcoin that can scale it to billions of people and I was sold. And this was actually back in 2014 when I first learned about this concept. So a lots happened since then, and I'm excited to chat about it today.

Brett Messing: (02:47)

So what is a use case for the Lighting Network? Because you know, I think for many people they look at Bitcoin, they see the price go up, particularly I think Americans, they don't see the utility of it. And I think the thing that's interesting about Lightning is it is bringing utility to Bitcoin. So why don't we talk about what Lightning can do? Why are we so excited?

Elizabeth Stark: (03:11)

Definitely. So Bitcoin's first killer use case or killer app is that of Bitcoin the asset. So in 2009, Satoshi, third January 2009, the [inaudible 00:03:22] creator of Bitcoin launched the Bitcoin network. And everyone's familiar I'm thinking here today with Bitcoin the asset. You buy it, the price has gone up substantially. The community has a meme. We call it number go up technology, right? The idea that the price of Bitcoin will go up and there are only 21 million that ever exist. But what got me interested in Bitcoin was less of the asset element and more of the idea that Bitcoin can really be this internet of money. So with Lightning Network we're actually building Bitcoin, the monetary network, and it's really about three years old. So Lightning initially launched as a protocol in 2018 on the main Bitcoin network. We call that main net. My company, Lightning Labs built some of the leading tools for developers to build on this technology.

Elizabeth Stark: (04:06)

And the goal there is to have internet native digital money. If Bitcoin is just the equivalent of digital gold or a digital rock, then we don't actually tap into the use cases where you can natively embed payments on the internet and have programmable money. So the goal with Lightning is really to enable this. So you asked about use cases. So the way that I think about it, in the early days of the internet, people didn't envision the use cases that are commonplace to us today. Something like a Google, a Wikipedia, Airbnb and Uber, that's the same for the internet of money. There are all sorts of use cases. For example, in game payments for video game developers, streaming SATs, or Satoshis as we call it, for streamers, for podcasters, for people, creators on the internet. We also have the ability to have cross-border payments instantly with extremely low fees, adoption and emerging markets.

Elizabeth Stark: (04:56)

So there are these use cases that weren't previously possible. And then also people that did not previously have access. Some people think, okay, why do I need Bitcoin today? I have my credit card. Well, there are billions of people around the world that do not have access to the existing credit card networks who charge something like 250, maybe even 300 basis points for a transaction. And we're actually seeing today adoption in many of these markets. El Salvador, some people may have heard recently made Bitcoin legal tender. Today, Starbucks, there's a great company called IBEX Mercado, McDonald's, one called OpenNode and a variety of major retailers are using the Lightning network today, built on the technology that my company has created. Which if you'd asked me a couple months ago if this would happen, I probably would not have believed it, but welcome to 2021. So there are huge opportunities for people globally that don't have access to the financial rails that we do here in the US.

Brett Messing: (05:53)

So you mentioned like Uber and Airbnb, sort of disruptive technologies. It seemed to me that the thing that exploded in my mind when I heard about Lightning was the remittance market. And can you just explain how that works? So let's just say I'm sending money to someone in Mexico City on Lightning. I just think people would find it interesting just how functional it is.

Elizabeth Stark: (06:18)

Definitely. So there's some great companies already out there. There's one called Strike, another one called Paxful that are enabling cross-border payments with Bitcoin and Lightning. So the way that this would work is a user using a service could convert say US dollars to Bitcoin's sent over the Lightning network and Lightning enables these instant high volume transactions. And then it could be converted back at the point of receipt to say peso. And you have Western Union and major players out there that are charging very high fees, especially for low value transactions. You might have to physically go to a location. All this can be done with a smartphone, right? And we see in emerging markets a huge amount of smartphone penetration, many people have access to those. So in these markets, people are able to leapfrog over the outmoded technologies to be able to adopt instant, high volume transactions over Bitcoin and Lightning.

Elizabeth Stark: (07:13)

And one key element is people say, okay, volatility. That can be a question. Well, when you have instant transactions and you want to go from USD to Bitcoin over Lightning to another currency, say peso, you actually aren't exposed to that volatility, which is key. In that case, of course, some people want Bitcoin. I like to say, Bitcoin is a millennial retirement account. I have a number of friends here in New York City, they are very short on dollars and they hold a lot of Bitcoin as part of their strategy.

Elizabeth Stark: (07:40)

But it depends on the individual. But in this case, Bitcoin is serving as a value transport layer, as I like to think about it. And the vast majority of users in the future likely will not know that they're using Bitcoin. They just think they're sending value on the internet and maybe denominated in their local currency. And that's the way the internet works today. For example, people that use say email may not know that SMTP is a protocol underlying email. They just use their Gmail. Email's not even that cool anymore. But that will be the same with Bitcoin and Lightning and the internet of money.

Brett Messing: (08:14)

Okay. So we mentioned El Salvador, just like I guess in the development of Bitcoin, which you've been a part of for a long time now, big deal, little deal? I think when I think about what you're doing, you're really bringing Bitcoin to the masses. It's like, what does this mean Bitcoin being legal tender in a country?

Elizabeth Stark: (08:40)

Definitely. So my company Lightning Labs, we're about 25 people these days and we have a number of brilliant developers and credit, for example, to my co-founder and our CTO, his name is Olaoluwa Osuntokun, who was born in Nigeria, came to the US when he was younger and has seen the value of all of this, especially with family back in Nigeria, brilliant engineer. And so if you had told me even six months ago we would have seen nation state level adoption of both Bitcoin and Lightning, I would not have believed that. And it happened. And even though, El Salvador being a small nation, six some odd million people, I believe it is historic and significant that this level of adoption has occurred. And a number of retailers are now using the Lightning network. So Bitcoin, the community loves Twitter, right? People are on Twitter.

Elizabeth Stark: (09:37)

I'm sure you've seen a lot of that. And there was a tweet this week because last Tuesday was the launch of this law in El Salvador and a number of these retailers were using Lightning, the technology that we had built called L and D from my company, and a fee at Starbucks for a user paying over the Lightning network was five hundredths of a cent, which I thought was just incredible. I mean, compare that to the types of fees that people would pay for the traditional card networks. So there's a joke in the community about paying for coffee with Bitcoin and in the US it is not necessarily hard to pay for coffee, but in many other emerging markets, the rails are not there and they're actually able to use this technology. So to me, I believe it is quite significant. There's also been a domino effect.

Elizabeth Stark: (10:27)

There's a great company out there called Galoy who's building an app called Bitcoin Beach. And this actually is what got the whole El Salvador movement started. They have a community in the south of El Salvador, a surfing community, where they've been using Bitcoin and Lightning for two years now in what we call a circular economy. So their vendors don't have access to card networks, but they have smartphones. So they're actually using Bitcoin and Lightning to send and receive money and vendors are able to accept it. And to me, that community is just the big beginning. That company has heard from so many other governments, communities around the world that are interested in this technology. So El Salvador is the first, it's certainly not the last. And I believe we will see a variety of other particularly emerging market nations move forward on Bitcoin adoption.

Brett Messing: (11:13)

So you mentioned Twitter, which is important in the Bitcoin community, the community sort of lives on Twitter. No one or very few people have done more for Bitcoin than Jack Dorsey, who also had the wisdom to invest in Lightning Labs. Jack Dorsey, according to public reports is about to integrate Lightning into Twitter. Can you speak about, to the extent you can, what is forthcoming? Again, I think the thing that's really interesting is the utility and what services Lightning is empowering.

Elizabeth Stark: (11:50)

Definitely. So I'm just speaking from kind of the outside here as an observer. And yes, Jack Dorsey is one of our investors and has been incredibly helpful and also just somebody who really understood Bitcoin at the outset and seeing that it can be this native protocol for value and currency of the internet. And so I believe that fits into a strategy with Twitter. So part of what got me interested in Bitcoin and Lightning in the first place is this idea of internet native digital payments and the creator economy. And what better place for this than Twitter? Yes, the Bitcoin community loves to, sometimes they have lots of fights on Twitter and debates. I've definitely been in the middle of those, but also there are a lot of people that will create tweetstorms and post videos and have all sorts of really interesting, I mean, I learn so much from Twitter and it's a way for me to find really interesting links and research and discover new people.

Elizabeth Stark: (12:45)

We've made hires for Lightning Labs of people from Twitter. And we love memes in the Bitcoin and Lightning community. So the idea there is, well, okay, Bitcoin and Lightning enable instant high volume, low fee transactions around the world globally. If we were to use existing payment rails, and I think what they would likely do is have a variety of options. Some on the existing rails, some using Bitcoin and Lightning, you can get to far more people globally than you would be able to, and it makes a lot of sense. You have a younger population as well that very much wants more Bitcoin. They want to be able to hold us. They want to be able to earn Bitcoin. Sometimes people say, well, I don't want to spend Bitcoin, but Lightning enables people, unlike say a Visa, sometimes people say, okay, Lightning's like a decentralized Visa.

Elizabeth Stark: (13:30)

And there are elements of that, but you don't really earn money on Visa, but with Lightning you can. So we see a lot of really interesting use cases like the Twitter one, which will enable content creators to earn over Lightning. There's an incredible company called Stack, which enables people globally, Latin America, Southeast Asia, to earn Bitcoin over Lightning performing small tasks like for AI and machine learning. There's another one called Zebedee for internet gaming where today gamers in Brazil are earning more over Lightning with Bitcoin than they would in a normal job for their salary by actually just doing what they love, which is playing video games. So we're able to unlock these incredible opportunities that would not have previously been possible. And that's where I see Twitter fitting in as well.

Brett Messing: (14:13)

So it's sort of like tipping, right? Is that a way to think about it, right, that if I post something you think it's cool, Lightning's going to enable you to tip me in Bitcoin?

Elizabeth Stark: (14:26)

Yeah. I mean, there are all sorts of interesting examples. People could participate say in certain campaigns as well. There was a really incredible campaign recently where a group called Bitcoin Smiles in the Bitcoin community raised money for people in El Salvador who could not afford dental or hence smiles. And just, this community, people by the way, they do this on their nights and weekends, this is not their job. They just love it and they really care. And so you could have charity contributions and things like that as well. I think there are a lot of really interesting opportunities.

Brett Messing: (14:58)

So I want to just scope out a little bit, as I'm sure everyone can tell you're super enthusiastic about this. And the thing that brought you to it is sort of a passion for open source decentralized networks. I can speak for myself, I don't think I fully appreciated the significance of a decentralized network until recently. And I would say the China ban on mining hammered it home for me, but I'm probably still not as far along on it as I should be. Can you just speak to that? And I mean, I want to hear your answer, I'm sure other people do too as well.

Elizabeth Stark: (15:33)

Definitely. So the way that I like to think about it, being the internet geek that I am, in the early days of the internet folks may remember AOL, CompuServe, Prodigy, and the like, right? Those are proprietary networks. To have an AOL keyword, you had to go to AOL and get permission. And then there was a worldwide web and anybody could build on the web. And ultimately it was the web that won out in terms of all of the incredible sites and businesses that have been built on the web today. And I see the same for Bitcoin as this internet of money in that the ability for anybody to build on top of Bitcoin, you don't have to ask permission, you're able to do so and Lightning makes it easier for developers to build on top of it because you have these instant transactions as opposed to the 10 minute block time of Bitcoin. You have the scalability as opposed to the five to 10 transactions for a second.

Elizabeth Stark: (16:22)

And then you have the fees that can spike on the base layer of the Bitcoin blockchain. So the open nature of Bitcoin and Lightning means that it's available to people around the world. For example, there's an incredible entrepreneur named Bernard Parah out of Nigeria who just built an application called Bitnob. And he just spun up a group of developers, and now they have this business and they're building for Bitcoin and Lightning, and he didn't have to go and get permission. It's just open. And now you can use the Strike app to actually send remittances to Nigeria because Bernard was able to tap into this technology and the Lightning network. And to me, that's what's extremely powerful. And then some people might ask, okay, well, there are all these other cryptocurrencies, why focus on Bitcoin, as my company Lightning Labs and as our community in the Lightning Network community? And the answer is ultimately network effects.

Elizabeth Stark: (17:15)

Right now, Bitcoin is the most secure cryptocurrency. It has the most hash power for miners backing it up. And folks are probably well aware, it is the most valuable cryptocurrency with the most adoption around the world. And in emerging markets, it's even more so by the way. In Nigeria, 32% of Nigerians use cryptocurrency, the vast majority of which is Bitcoin. And then something like 50% of Nigerians are 18 and under. So there's a very young population that is very excited about this technology. And we see that in other places, in emerging markets and around the world. And of course here in the US, lots of incredible developers and builders on this technology. So my answer there is the idea that you have all these existing users, you have people that are building upon the technology. There's something called Metcalfe's law. And one of my favorite researchers, Lyn Alden has written a lot about that.

Elizabeth Stark: (18:08)

Check out her macro research and her Bitcoin research. And she has a piece on network effects. And she talks about how breaking a network effect means if something is not 10 times better, it will not break it. If it's slightly better, it's very difficult. So Bitcoin already has a substantial network effect. And there's a concept of Metcalfe's law, Robert Metcalfe, who created this for networks in the internet, as each individual user joins a network, the value of that network goes up exponentially. So to me, the open decentralized nature of Bitcoin combine with the network effects, and then you have Bitcoin, the monetary network, which is Lightning combined with Bitcoin the asset, that creates this virtuous cycle. And we call it a flywheel effect, which just keeps growing and growing. And we've seen a lot of network growth. A lot of people running these nodes on the network that are like servers, and a lot of developers building in the technology and an increasing amount of capital that is deployed onto Lightning as well.

Brett Messing: (19:02)

So we have a minute left, there are about a hundred something million people that own Bitcoin. And there are projections that in four years, that number will be billion, billion plus. What gets us from here to there? That's S curve stuff. That's an acceleration of adoption. What do you see as the driving forces for that?

Elizabeth Stark: (19:29)

At the end of the day, real use cases for real people in those categories of enabling use cases that weren't previously possible and enabling access for those that previously did not have it. And there's something in the broader, I'm in this cryptocurrency world in the industry, and in some cases I think people are working on solutions in search of a problem. And I really care about solving real problems for real people and making this technology accessible. In the early days of Bitcoin and Lightning, even three years ago, it was hard to use.

Elizabeth Stark: (20:02)

It was like command line based, it was like the early days of the internet. Now we're seeing it become more and more accessible, more and more usable. And I think in the early days, people underestimated the power of the internet. There's this great quote by an economist, by 2005 the internet's impact on the economy will be no greater than the fax machines. Clearly that person was wrong. And similarly, I think a lot of people underestimate Bitcoin and Lightning, but at the end of the day, I would highly recommend not to sleep on this technology as my friend Max Webster wrote because we're really at the beginning and there's so much left in store.

Brett Messing: (20:33)

All right. Fantastic. Well, thank you very much.

Elizabeth Stark: (20:36)

Thank you.

The Future of Private Markets with David Rubenstein & Jeff Blau | #SALTNY

The Future of Private Markets with David Rubenstein, Co-Founder & Co-Chairman, The Carlyle Group. Jeff Blau, Chief Executive Officer & Partner, Related Companies.

Moderated by Matt Brown, Founder, Chief Executive Officer & Chairman, CAIS.

SPEAKERS

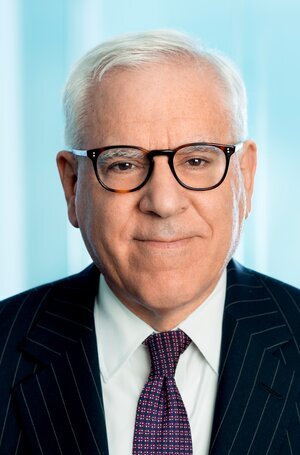

David Rubenstein

Co-Founder & Co-Chairman

The Carlyle Group

Jeff Blau

Chief Executive Officer & Partner

Related Companies

MODERATOR

Matt Brown

Founder, Chief Executive Officer & Chairman

CAIS

TIMESTAMPS

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Matt Brown: (00:07)

David, Jeff, welcome.

David Rubenstein: (00:10)

Thank you for having us.

Jeff Blau: (00:11)

[crosstalk 00:00:11].

Matt Brown: (00:12)

My name is Matt Brown. I'm the founder and CEO of Case. I'm really honored to be with two great business leaders in the private market space. David Rubenstein, Jeff Blau. We have a somewhat limited window here, 35 minutes, but I don't think either need a big introduction, but I think we would love just to have you each to spend a second introduce yourselves and we'll dive right in.

Jeff Blau: (00:39)

So thank you for having us today. So I'm Jeff Blau, I'm the CEO of Related Companies. For those of you that don't know, we're a large real estate development company based here in New York City, right across the street. You might know the Hudson Yards that we built and own as well as Columbus Circle, which is now called Deutsche Bank Center, used to be Time Warner Center. Across the country, we develop in most of the major markets throughout the US, and then London outside. We employ about 4,000 people. Today one of the largest real estate development companies in the United States.

David Rubenstein: (01:15)

Okay. I'm David Rubenstein. I'm the co-founder and co-chairman of the Carlyle Group which is a global private equity firm operating in 35 different cities around the world. And we manage about $276 billion currently. And we are actively investing in this environment and we think it's a pretty attractive environment in many ways.

Matt Brown: (01:37)

Great, welcome. Today's panel creating value and democratizing access in a post pandemic world is our title. I think with David and Jeff, we could take this in a lot of different directions. So let's just kick off. The last decade has been just astronomical in terms of private markets growth, both on the real estate side, Jeff and David on the private equity side. Let's just talk about some of those drivers. What's going on in the environment that's propelling your areas for just such extreme growth?

David Rubenstein: (02:08)

Well, the charm and good looks of the founders of global private equity firms has probably been the principle driving factor would be my guess, but if you don't believe that, the returns have just been better than any other asset class. Private equity over the last 10 years, 15 years, 20 years, 30 years and so forth, and almost every year outperforms public equities by 300 to 500 basis points depending on the year and the [inaudible 00:02:31] and so forth. So people have consistently said, well, if I can get better rates of return, I should do that. Now I have a higher risk factor, but over the years, people have included that private equity and its various forms buyouts, venture capital, growth capital, infrastructure is not as risky as was thought to be the case 30 or 40 years ago. So if you don't have the high risk that people thought you had in these so-called alternative investments, and you're going to get a higher rate of return, people are willing to pay the higher fees involved and willing to have the longer holding period.

David Rubenstein: (03:01)

So that's basically what's driven is that the rates of return have just been more consistent and the industry is much more mature in the sense that the people in the industry are more sophisticated about avoiding bad deals and even though we're paying reasonably high prices by normal standards, the industry has so much more talent to make these companies work than it did 20 or 30 years ago. And I think people feel much more comfortable than they did 20 years ago in investing in this area.

David Rubenstein: (03:26)

20 years ago and obviously 20 years ago was a tragic occurrence right near in this site where we are today, 20 years ago, you had less than a trillion dollars invested in overall private equity, all assets [inaudible 00:03:41]. It was less than a trillion. Then you're all over private equity is probably eight to 9 trillion. So it's gone up dramatically in this 20 year period of time. And I think the rates of return have been very, very consistent and people believe they will be consistent in the future. And because interest rates have been low, it's been driving people to get out of traditional, fixed income kind of investments. And they go into things that are going to yield better than the low things you get on treasury bills or other corporate bonds.

Matt Brown: (04:07)

Jeff, what about the real estate world?

Jeff Blau: (04:08)

So I would say similar to private equity, if you think back 20, 30 years ago, real estate was never really considered an institutional asset class. And so spreads were wide and it was a lot of inefficiencies in the market over this period of time. People have institutionalized private investment in real estate assets, whether it's opportunistic investments through development acquisition, or even more recently, some of the very, very large core funds that have been created really as interest rates have come down so low, the spread that you can make owning real estate is greater than almost any other point in time.

Jeff Blau: (04:45)

And so there's been huge inflows into core ownership of real estate, providing steady recurring income, cash flow, and tax benefits to investors. And so if you look at it today, it's a much more institutionalized product and capital flows are really greater than they've ever been into the real estate sector.

Matt Brown: (05:04)

Just staying on that, we've been through a pretty dramatic 18 months. Different businesses have succeeded. Others have turned the lights off. They always do this when I start talking, by the way, I should have told you that. The COVID-

David Rubenstein: (05:21)

Actually, maybe our time is up already, I don't know.

Jeff Blau: (05:24)

Now we can see everybody.

Matt Brown: (05:26)

Anthony Scaramucci just wants to see what we're made of, I think.

David Rubenstein: (05:28)

Okay.

Matt Brown: (05:29)

See? I can see him with a little light switch. Jeff, the pandemic, the global pandemic has negatively impacted so many companies on the flip side. So many have been beneficiaries, specifically around the real estate industry and directly related. Walk us through kind of what the last 18 months have been for you, how you reposition the firm.

Jeff Blau: (05:54)

So I would say COVID has really thrown everything for a loop. It's been the wildest swings I could possibly imagine in the past 30 years in real estate. You almost saw this vacuum of people leaving cities, the core urban markets, apartment buildings emptying out, retail stores going out of business. People really even today aren't back as much in their offices.

Jeff Blau: (06:20)

And yet you look at the last 60, 90 days, you're seeing a complete reversal of that trend. So to give you some high level numbers, we own one of the largest apartment portfolios here in New York. So at its absolute peak, that portfolio went from 98% occupied to 83% occupied. In order to get people to sign leases, we were giving away three months rent. That portfolio is back to 99% occupied with no free rent. So basically we're kind of even plus 1-2% to pre COVID numbers. So that's been a remarkable swing and really, I think that's been around this timeframe, Labor Day, September, back to school, I think the Delta variant has put a little bit of a damper on return to office, but still, I think there's been a huge inflow of population back to the cities.

Jeff Blau: (07:12)

Now, condo sales have picked up again. We've had actually the last 60 days have been the most robust condo sales since 2013 here in New York. S we have seen a tremendous swing. It's been a pretty wild ride. I would say the other thing that's happened is people have further rediscovered what we would typically have called secondary cities. So our offices are in New York, Chicago, LA, San Francisco, Boston, DC. And that's where we've been most active, but there are great cities and we've always been small investors, but now have become much larger in Austin, Charlotte, Denver, West Palm beach. These were markets that we had typically called secondary, and I think there's been a lot more interest in those cities and think they'll really become primary markets for many people.

Matt Brown: (08:03)

Same question to you. I just want to ask one more question, but Jeff, a lot of people say, when will Manhattan be back? Being here in Manhattan. And of course back is a bit in air quotes. When is Manhattan back?

Jeff Blau: (08:14)

I do think a lot of Manhattan is back. If you just walk around... First of all, you can't get a reservation, you can't go out to dinner. The restaurants are packed and the West Village is packed. The meatpacking district is crowded on a Saturday. So New York is feeling like it's coming back. I would say the only thing that is not really back here are people's return to the office. And I think that's something we can talk about, but I think that's going to change a little bit over time and that's going to be a slower return.

David Rubenstein: (08:47)

For the country as a whole, the pandemic has been a tale of two cities. If you are uneducated, you work with your hands, you can't afford childcare, you don't have broadband, this has been a terrible time for you. And you've fallen further and further behind than where you were before. If you're in the financial service world and everybody here presumably is, this has been a pretty good time. The private equity world has done more deals, exited more deals, raised more money than any other time in its history. So if you'd flown in from Mars and said, okay, a pandemic is going to strike the entire world and particularly the United States where we've lost 650,000 people, how can the private equity world do so well? Well, there's lots of reasons for it, but technology enabled us to basically raise money, invest money, and exit deals and do road shows for IPOs and things like that without having to actually physically go anywhere.

David Rubenstein: (09:41)

So it's been amazing. And the question will be going forward, will people want to physically go travel around the world to raise money? Will people want to physically go on road shows again, the way they used to on IPOs, as opposed to doing virtually? Nobody knows the answer to that for sure. I suspect it'll be some homogenized kind of view of what will happen, but the private equity world could not be honestly in better shape. The hardest things in private equity right now are if you're a first fund. People don't like to put money into a first fund, unless they meet you in person, appropriately so. There's a due diligence standard. You have to meet the person.

David Rubenstein: (10:14)

So if you're raising a first fund, it has been more challenging now in this environment. But if you're raising a third fund, a fifth fund, an eighth fund, you can get your re-ups done if you have a reasonably good track record very, very quickly. And if you're doing deals, it saves a lot of wear and tear. You don't have to travel as much. So it's been a blessing in disguise for people who are in the financial service world. For people who are not in that world, the people I referred to earlier, this has been a terrible situation, and it's not going to get any better anytime soon, because we still have less than 35% of the people are not vaccinated yet. And that isn't probably going to change anytime soon.

Matt Brown: (10:51)

David, why would this great change in behavior to our benefit, virtual communication, the change in behavior, virtual communication now is stepping in-

David Rubenstein: (10:59)

You mean going forward?

Matt Brown: (11:00)

Yeah. Going forward.

David Rubenstein: (11:02)

Well, going forward, people are used to, let's say doing Zoom meetings now, but I think there's a feeling that once you can travel, probably you should reconnect with people. There's nothing quite like a personal connection which you can get when you're having lunch or a dinner with somebody or meet them in person. I think there'll be a feeling you should go out. But I don't think people will fly around the world to get a re-up on a fund when they can do it virtually. I think you won't have people traveling quite as much for business travel. I think that's pretty obvious to all of us, but the private equity world's biggest challenge going forward is probably whether prices are going to be so unattractive because they're so high that people feel compelled to do deals because they have a lot of money.

David Rubenstein: (11:46)

And then when the inevitable interest rate rise occurs at some point, presumably after the midterm election, you then see evaluations going down, whether people will run for the exits and say, okay, the great recession is here again. And so people are getting nervous. I don't see that on a rise anytime soon. I don't think interest rates are going to be raised, certainly not before the midterm election. And I don't think we're going to see any big tapering anytime soon, but clearly if we go to a normalized interest rate situation, there'll be some correction for sure.

Matt Brown: (12:13)

Jeff, what behavior has been changed do you think by the pandemic that you see in the real estate world that most likely will not change back?

Jeff Blau: (12:22)

Well as I was mentioning, I definitely think that there's a change in the way people use their office. I think companies, certainly larger companies will continue to have pretty much just as much office space as they have today. But I think there's going to be a lot more flexibility around how it's used. And I think whether it's four days a week or three days a week, I think companies are going to have to offer as a concession amenity to attract employees that flexibility in the workplace. Yet, when I talk to the heads of some of the big tech companies that say, oh, we can go remote, they will privately acknowledge that they really can't have culture creation, productivity, and innovation at home on Zoom.

Jeff Blau: (13:06)

And so what they're really trying to do is figure out how they coordinate this flexibility in the office. So maybe a whole group has to come in all the same four days or three days so that when they are in the office, it's much more of a collaboration effort that's happening. And that may help. That may force us to redesign how spaces are built out. There might be more meeting spaces, more gathering spaces, fewer private offices, but ultimately people are going to need to get back to the office and we're seeing it now in corporations actually taking more space in anticipation of all the growth that you just talked about, even though there's going to be that flexibility in the workplace.

Jeff Blau: (13:48)

And then the other thing David touched on, I do think that there will be some permanent changes in business travel. I think leisure travel people absolutely want to get back and leisure travel business has been unprecedented over the last 90 days as people felt a little bit freer to get out of the house, but we haven't seen the same levels of business travel yet when we had 2,500 people here today. So I think that's a great test to people gathering and getting together and staying at our Equinox hotel at Hudson Yards. Thank you for those of you staying there. And so it will be back, but I think business travel will be a slower recovery than the balance.

David Rubenstein: (14:30)

Great events in history tend to take a long time to have an impact in the way people live and work. So the industrial revolution took roughly a hundred years before people really changed the way they lived and work and became more of an industrial economy, an urban economy than an agricultural economy. The things we've lived through, it took maybe 25 years for the internet to really change our lives. It took smart phones, maybe four or five years to change our lives, social media, two or three years. In basically 18 months, we have changed the way we have we're going to live and work considerably. Yes, people are going to come back to the offices, but probably not five days a week and quite the way they did before. And people aren't going to travel quite the way they did before. So we've changed the way we live and work.

David Rubenstein: (15:11)

And those people that adapted this well are going to be quite successful. Private equity people tend to adapt pretty quickly. I think real estate people probably adapted pretty quickly. People in the financial service world adapted quickly, but all of us are fortunate because we have certain skills. We have certain technologies available to us. I think for the country itself, it's going to be a bit of problem before the country can really get back to where it was before for people who are at the bottom of the social and economic strata.

Matt Brown: (15:37)

David, many investors in the audience. We hear the word bubble when we think about private equity now, real estate. Most people don't believe there is a bubble. Where do you come on the private equity bubble that everyone seems to be hinting at?

David Rubenstein: (15:55)

Sir Isaac Newton, one of the smartest men who ever lived, he invested in the South Sea Corporation and he got out before it peaked. And he was upset with himself. He said, I'm a genius, but how come I got out and stocks still going up? So he went back in and ultimately was a bubble collapse. So people have a temptation to feel that they're missing something great. And so that's why people are still investing pretty heavily. They're afraid that they're going to miss something great. And maybe they will miss something. I think people have to be cautious, but you never know you're in a bubble until it's over. And as soon as we go into the next bubble and there's a bubble in some area and I'll think all of a sudden people will come out of the woodwork with their memos saying, well, I told you this. Of course, these memos were filed away.

David Rubenstein: (16:40)

They weren't given to people at the time or they weren't made public. People always were saying they predicted a bubble. Right now, I don't think we're in a bubble. Clearly, we're not in the kind of bubble where we had the 1999, 2000 internet bubble. They were kind companies with no earnings, no revenue, virtually nothing and that they had high valuations. I don't think that's quite the case today. The valuations are a bit high in some cases for some growth companies. But I do think that they are transforming the way we live and work in ways that I think we will grow into those valuations. So I don't think we're in a bubble, I'd say Palm Beach, real estate might be in a bubble in some cases, and maybe South Hampton and East Hampton real estate might be in a bubble. But generally I wouldn't think we're in a bubble of the type we have to worry about the way I felt we had to worry about things in 1999 or 2000.

Matt Brown: (17:27)

How would Carlyle reposition right now if you actually believed you were in a bubble? What are some of the immediate at things that you would be doing?

David Rubenstein: (17:35)

Well, it's difficult to talk about that because I'm afraid I'll be misquoted in saying that we are in a bubble. I don't think we are in a bubble, but if you were in a bubble, you would obviously slow down the amount of money you're putting out and people are putting out records amounts of money. People are afraid they're going to miss the next great thing. So anybody who thinks they're in a bubble should obviously slow things down, but go back to the companies you've already invested in and see whether they have debt that can tolerate some kind of slow down in repayment. Obviously most of the buyout deals today are done with covenant light debt, so it's tougher to default than it was 20 years ago. And so I think that people are much more experienced in dealing with downsides than they were 10 years ago or 20 years ago.

David Rubenstein: (18:19)

So I don't think we're in a bubble. There might be in certain sectors some people are too anxious to put money in some things. So some people would say cryptocurrency is a bubble. I don't subscribe to that view necessarily. I don't own any cryptocurrencies, but I know there are some people and people I've interviewed recently have said, yes, this thing is all going to zero. But of course, when am I going to go to zero? Who knows how long it's going to take. I would say cryptocurrencies clearly have a market. And I would not bet against it because I think that would be difficult, but at some point probably some of the air will come out some of the cryptocurrencies, I just don't know which ones.

Matt Brown: (18:55)

Jeff, speaking of West Palm beach and Palm beach, where I know you view that as a secondary city. I was there recently and I think I saw a property smaller than my first Manhattan apartment asking some of the neighborhood of 10 or 12 million dollars. What's going on down there? And same question to you. I know you don't believe we're in a real estate bubble right now, but tell us what's going on that space.

Jeff Blau: (19:20)

Right. Well, I think you have to separate out some of the very unusual special spots like Palm Beach, Hamptons, Aspen in terms of single family home prices that have really escalated during this period of time and then the institutional investment world in which many of us operate. So if you talk about the institutional investment world, I don't think that there's a bubble there in real estate either.

Jeff Blau: (19:45)

I think people are investing in real estate, essentially one of two ways where one is an opportunistic invest where we've been very successful over the past year investing in situations that have found themselves in trouble because of COVID. And we've been able to put out a lot of capital in that space through opportunistic investing, but really where the tremendous capital flows are now is a result of low interest rates. All right. And so you have to have a view on interest rates to determine if you think we're in a bubble or not, but people have been looking for alternatives to essentially 0% returns. And so investing in stabilized core assets and getting that spread in core real estate has been a great investment over the past several years. And I think you'll see that continue into the future. With regard to West Palm beach in particular, we have been very, very active in that market for a long time before COVID and I'll say unfortunately, maybe for New York, but it's good to be on the receiving end.

Jeff Blau: (20:53)

We've seen a lot of people move businesses, mostly smaller financial service firms, family offices, to Palm Beach. People have moved, put their kids in school down there and have taken office space and today we really control almost the entire class A office market in West Palm beach. And that has completely filled up over the last 12 months, as I said, mostly people from here. And so we are monitoring that shift back and forth. People typically aren't moving their businesses completely, but opening secondary satellite offices. And interesting in many cases also expanding here in New York at the same time. But West Palm has been, has been terrific.

Matt Brown: (21:40)

Qualified opportunity zones are somewhat the opposite of Palm Beach in many ways. That's an area of focus for related, maybe a quick brief description on the QOZ opportunity itself. And then how are you focusing on it at Related?

Jeff Blau: (21:56)

Sure. A qualified opportunity zone is an area designated by the federal government to encourage development in those areas or to encourage businesses to move to financially depressed neighborhoods by zip code. And essentially what it does is it allows you to sell an asset, whether it's a corporation, shares of a company, or a real estate asset, and reinvest that gain into something, real estate development, a new business in a qualified opportunity zone area, and you can defer the taxes on that gain until end of 2026. And then even when that tax comes due, you only owe 85% of what would have been due back then. And then the money sits invested for 10 years and all the earnings during that 10 year period is not taxed at all, has no tax on it. So it's been a great opportunity for people to move money from gains that are sold into qualified investment opportunity.

Jeff Blau: (23:02)

And we have made a business of investing in real estate assets, typically new construction development assets in qualified opportunity zones. So raising money from individuals, placing that money into qualified opportunity zone real estate developments, and then we hold and manage those assets to maturity at the end of the 10 years, at which point we'll sell those assets and return the capital on a tax deferred basis for the investors. So it's really been a great product and really has created a lot of investment in those areas throughout the country.

David Rubenstein: (23:37)

I personally invested in a large one associated with the Boston Housing Authority.

Jeff Blau: (23:41)

Should have gone into our.

David Rubenstein: (23:42)

[crosstalk 00:23:42].

Jeff Blau: (23:42)

You didn't come into our funds?

David Rubenstein: (23:44)

I didn't go into a fund, I did it directly, but-

Matt Brown: (23:47)

You can access his fund in our platform if you want.

David Rubenstein: (23:49)

But I do think that it has potential to be very attractive, but I didn't do it because it was the tax consideration because to qualify for the task consideration, sir, it's complicated. And obviously as you know, it doesn't work for everybody. On the other hand, there are some good investments in these areas, whether or not you take advantage of the tax zones or tax opportunity or not. But the lesson I wanted to talk to people about is this, very few people knew about this in the Trump tax cut. It was lobbied through by Sean Parker among others, and it was done, I would say relatively quietly, at least for the general public, when the bill was passed, people saw it was in there. You're going to see the same thing in this current tax bill.

David Rubenstein: (24:34)

We're not going to know what's in the tax bill until it passes. The tax bill probably won't pass until the last day in Congress or so. And at that point I suspect there'll be a lot of things in there. So look for lots of investment opportunities or tax advantaged investments opportunities in the new tax bill. I don't know, who's lobbying them through at the moment. I'm not, but there will be some in there because every tax bill has surprises just as this one was a surprise to many people in the investment world.

Matt Brown: (25:01)

David, speaking of the US government regulation, there's always been that delicate dance between the private equity titans and the SCC and the US government trying to regulate. What's the state of play right now? Is the government helping grow the businesses? Are they worried about oversight?

David Rubenstein: (25:21)

I think the government of the United States has a lot of challenges right now and I don't think their biggest challenge is trying to figure out how to make private equity do things that it's not otherwise doing because of market forces. So we have not been anybody's sites relatively speaking. And so there might be some changes in the tax bill that might affect private equity, but generally people in Washington are more worried about regulating cryptocurrencies or other things and not private equity in part because we haven't had a lot of things that attract attention.

David Rubenstein: (25:49)

When you have a lot of bankruptcies, that attracts attention. People lost a lot of money, that attracts attention. That hasn't happened in private equity for a very, very long time. And as a result, I think private equity is not something that the administration is focused on or Congress is focused on. There may be some modest changes, but generally I don't expect big changes coming out of Washington in the regulatory or legislative area that's going to affect adversely the private equity world.

Matt Brown: (26:13)

One area that the US government is being quite proactive in is trying to allow more and more individual investors to gain access so they're actually on the side of the individual investor.

David Rubenstein: (26:21)

This is an important point. If you are a graduate of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, any great school, and you majored in finance and you're brilliant, but you decide to go to work for Teach for America and you make a modest salary. You're not an accredited investor. If your father is really rich and you flunked out of a couple colleges, but he gave you a hundred million dollars, you're accredited investor. So you can then do whatever you want with that money. It does seem a little ass backwards that the person who needs the higher rate of return that private equity might give you can't get it because he or she is not accredited.

David Rubenstein: (26:55)

Whereas the idiot who has a lot of money, he can go do what he wants or she can do what you wants. So it does seem strange. And finally, I think Washington is raking up to this and they are going to do things that are going to make it easier to democratize private equity for people that probably can benefit from some of these higher returns that are available in this industry. And I think you'll see 401k checkoff plans and other kinds of things that people will be able to do regularly get into various private equity areas. There's some challenges, but I do think five years from now, 10 years from now, almost everybody that wants to be in some type of alternative investment can do so even if you're not wealthy.

Matt Brown: (27:30)

I think that's right. I think at least the background there is that they wanted you to have enough money that you could lose the capital and not be impacted. So they're effectively saying that these asset classes are overly risky. That narrative has completely changed. And now they're opening it up. Jeff, when you think about product development and new funds that you're launching, do you think about the wealth management community or the individual investor and fund structures and strategies that make more sense for them?

Jeff Blau: (28:01)

So this has been one of the big shifts over the last couple years into real estate, where most of our investors have been historically institutional investors. You're now seeing more and more individuals come in through aggregators and some of the big real estate private equity firms, Blackstone, Starwood have taken the lead on this. We're doing this now at Related in terms of going to start raising capital through wealth management channels for debt. And these more core type investments that we've talked about. Your firm has been very active on aggregating capital from investors, individual investors, and investing into funds that were typically only open to institutional investors. And so I do think there has been, as you said, democratization in real estate and that has attracted tremendous capital flows.

Matt Brown: (28:50)

What's driving the demand, David?

David Rubenstein: (28:52)

Well, interest rates are so low. So people don't get the kind of rate of return that they normally would want from their fixed income investments. People see other people making money and so they get jealous and they say other people money, they're not smarter than me, why can't I make money as well? And the returns have been pretty consistent and the RIA market is gigantic. I spoke this weekend on Saturday to a group in Kansas City, several thousand people in an RIA group. And it was one firm. And every time I go to make a speech in front of large audiences these days, it's generally terms of groups of large RIA groups that have aggregated are one firm. There's an enormous amount of money in the RIA world. And the RIAs are increasingly feeling that their clients are going to be well served by putting money into some private equity firms.

Matt Brown: (29:41)

Well, Carlyle has done a great job on that. And just some numbers behind that, the RA channel advises between 10 and 12 trillion dollars in assets. That's excluding of course the larger wealth management firms like Morgan Stanley and Goldman, JP Morgan, just the RIA channel. Average allocation rates in the RIA space to alternatives are about 2%, so if you just project out what a 15, 20% allocation to alternative investments, whether it's real estate or private equity, we're now looking at a multi-trillion dollar jump all for the firms that want to be there.

David Rubenstein: (30:14)

Well, when private equity... It was in 1978 when the US government and, and Department of Labor said that ERISA funds could finally go into private equity or alternatives, and then Oregon and state of Washington, others went in and then they began having big allocations. And now you see typically for endowments, pension funds and so forth allocations somewhere between 15 and 20, 25%, in some cases, even 30, 35% to alternatives. The RIA channel isn't as high as that right now, people aren't putting as much in as higher percentage, but it will drift up to a higher number to reflect what I think the institutional market is recognized that the risks aren't as great as people thought, and the returns are much better than people thought.

Matt Brown: (30:54)

Jeff, there's this rise of the do it yourself investor. We're seeing it with Robinhood and Betterment and so forth. Now we're bringing serious institutional products, investment strategies into that market for the first time, which we all think is a positive. Who has responsibility for education or oversight to make sure that there's the right suitability in place? Is that now going to be put... If the SCC in Washington is loosening, that going to be pushed onto firms like you if we open up the channel for every individual to come in?

David Rubenstein: (31:30)

Well, my hope is that that people will feel they can write things in language that's understandable. Unfortunately, we now have a lot of legal documents that are very difficult for people to understand. I hope, and as we move forward, the things that educate people are going to be written in relatively simple English so that people can understand what they're really investing in, but particularly what the fees are and what the risks are. Sometimes if you read a prospectus, you really have a hard time figuring out what you're really getting into. So if the government of the United States does anything, I hope they will do a better job in educating people about the risk in simple English and the firms like ours have a responsibility to do that too. So I do hope that both sides, the firm that's doing the investing and the government will require people to really read something that's understandable before they go into some of these investments.

Jeff Blau: (32:24)

I also think it's you do have the wealth managers now in the middle of that. So there's one more group that's actually selling the product to the investors, whether it's a company like yours, or Morgan Stanley that is basically interacting between our documents and the individuals. And I think it's part of their responsibility to make sure that everything is explained properly.

Matt Brown: (32:47)

Do you think it's unusual that we can all board an airplane with an identification code that says you're a TSA, you're not a bad guy, but we still have to photocopy a picture of our driver's license to invest in a Blackstone fund and every other fund? When is innovation going to catch up here and just make this a little easier for people, because if you hope to attract the individual investor, it has to be simple and easy, understandable, but technology and speed and seamlessness has need to come into play here.

David Rubenstein: (33:18)

Well, I think that that is happening. And I think the technology world is such that now people are inventing things that'll do things like that and make it much easier so that you can invest in these kind of funds without having to fill out so many forms that you really can't understand or that take forever to get done that discourage people from doing it, but in the end, there's no such thing as a risk-free investment. Everything has some risk. I just think that people should be allowed to take a little bit more risk than maybe they're allowed to take today if they want to get higher rates of return other than what they've been doing and just putting things in treasury bills or something like that.

David Rubenstein: (33:51)

And the world's moving in that direction. And it's not just in the United States. Today, I would say roughly 60% of all private equity investments is still in the United States. So as the world moves forward and gets wealthier, you're going to see much more private equity and alternative investments in Europe and so-called emerging markets. It's going to take a while, but I do think at some point, you'll see the United States, not quite as dominant in the private equity world in the alternative world, as we currently are.

Matt Brown: (34:16)

Jeff, if you had to allocate a hundred dollars of your personal capital and limited to three buckets of investment strategy, either within the related umbrella or not within real estate, how are you waiting that right now, going for the current market and going forward?

Jeff Blau: (34:34)

I think about that all day, because that's where my money is allocated. But I would say you want to have a fair amount in opportunistic real estate assets because that's where you're going to get higher returns. But you also want to make sure that you have a bit of a nest egg and get current income and that's core. So I don't know, maybe I would probably be 60 to 70% and opportunistic in the balance [crosstalk 00:34:58]

Matt Brown: (34:58)

And what percent of an individual or an institutional portfolio should have real estate overall?

Jeff Blau: (35:04)

I think the pension funds today, you try to target between eight and 12% in real estate.

Matt Brown: (35:12)

David?

David Rubenstein: (35:12)

I would say that the greatest pleasure that you're going to get from investing is investing so you can give some of that money away. So I encourage all of you to think about your own philanthropic interests. All of us have thought recently in the last couple weeks and certainly in the last couple days about this country and some of the tragic times we've been through. And I think if people who think about what they can do to make this country better and give some of their money that they make from investing in real estate or private equity to things that I think makes the country better, I think you're going to feel much better about that.

David Rubenstein: (35:44)

And so I hope everybody here can just ask themselves, what are you doing to make the country a better place? What are you doing to give back to this country that made it possible for you to be as reasonably wealthy as you are? And I think when you find that thing and you give some money to it and give some time to it, you'll feel much better than even if you get a triple or quadruple on one of your investments.

Matt Brown: (36:03)

We're almost at time. I just want to ask you one last question each. You've both built and run great businesses. A lot of young people coming to work for you, with you, learning. If you were mentoring a young employee or an entrepreneur, what's the one piece of advice you'd give them?

David Rubenstein: (36:22)

Have intellectual curiosity, ask questions, read. You can't read too much. Learn how to write, learn how to speak, learn how to get along with people and have some humility about what you do if you accomplish something, because you'll get much further if you're humble. You'll get much further if you actually have intellectual curiosity and try to make yourself valuable to any organization you're in. Make certain that you're actually adding value. Specialize in something, know it well, and then help other people with their projects. As Ronald Reagan famously said, there's no limit to what humans can accomplish if they're willing to share the credit as well.

Matt Brown: (36:57)

Share the credit. Jeff?

Jeff Blau: (37:00)

I would say you have to pursue an area that you're passionate about. You have to enjoy what you do every day. And going back to what David said about philanthropy, a good portion of what we do all the time is focus our efforts on affordable housing development, because we think it's one of the most important things that we can do for cities and this country needs. And so being able to pursue a passion of mine, which is real estate development and being able to do that in an area where we're also doing good for society, I think that's really, that's the perfect career. And if you can position yourself that way, that's the best outcome.

Matt Brown: (37:35)

David, Jeff, thanks so much really enjoy it. Really appreciate it.

How COVID-19 Reshaped the Advice Industry | #SALTNY

How COVID-19 Reshaped the Advice Industry with David Bahnsen, Founder, Managing Partner & Chief Investment Officer, The Bahnsen Group. Karen Firestone, Chairman, Chief Executive Officer & Co-Founder, Aureus Asset Management. Josh Brown, Chief Executive Officer, Ritholtz Wealth Management.

Moderated by Sean Allocca, Deputy Managing Editor, InvestmentNews.

SPEAKERS

David L. Bahnsen

Founder, Managing Partner & Chief Investment Officer

The Bahnsen Group

Karen Firestone

Co-Founder, Chairman & Chief Executive Officer

Aureus Asset Management

Josh Brown

Chief Executive Officer

Ritholtz Wealth Management

MODERATOR

Sean Allocca

Deputy Managing Editor

InvestmentNews

TIMESTAMPS

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

David Bahnsen: (00:07)

New York was slightly different story, we reopened last summer, but we have a smaller presence in New York. We've doubled in size out here since, but it was easier to get away with kind of what was going on in New York than it was California, particularly Newport Beach where there was much less of a hysteria about things versus LA County. But I agree with Josh completely that all the technology apparatus pre-COVID was a very natural segue into what ended up taking place. We were big Salesforce users, we're big WhatsApp users, so there was the ability to use cloud and use digital communications internally where we didn't skip a beat.

David Bahnsen: (00:48)

The difference for us is... And I think there's a huge advantage for us right now versus all the wirehouses that aren't reopened and don't appear to have any intention of reopening their branches anytime soon... the client-facing aspect of the business. We have clients in 40 something states. We always have. There's a lot of remote communications, just like what Josh was talking about, when you have a national footprint, but to the extent that we have local presence, we really want the face-to-face. And we think it was a huge advantage for us last year that we were able to get in front of prospects and clients both through the second half of last year and all of this year, and we've reaped a lot of dividends from that.

David Bahnsen: (01:31)

This is something I remember when I was in training, coming out of dotcom, I was at a firm called PaineWebber, they got bought by UBS, and the then CEO, Jo Grano was giving us a speech about why we didn't need to be afraid of the e-trades and Schwabs and all this. And he said, there will never be a time in your life ever, where the really truly high net worth are... that you're going to be dis-intermediated. There's always going to be an industry for advice. And people were worried about that at the time, what they thought was cheap trading. I think it was like 20 bucks a trade or something. I remember throughout COVID thinking the same thing, the idea that we'll get to a point where this very well-established desire from high net worth people to have communion with their advisor, to have a face-to-face communication, to have events.

David Bahnsen: (02:22)

Events are a big part of our business too, like Josh was saying. We've started out doing them again. We had 250 people at a client dinner a few months ago in California, so we're back up and running our first event here in New York, it will be in another month. Larry Kudlow is an advisor on my team and he and I are going to speak together and that'll be packed out. And so those are the things that make you feel like you're getting back to normal. But the key issue for us is the face-to-face with the client where it's possible. I do not believe that can go away, I think people desire that personal relationship.

Sean Allocca: (02:57)

And so what have been... I mean, we'll give this one to you, Kari... some of the pain points that you've seen in the last 18 months in terms of the pandemic and how we overcome them at your firm? Have you seen similar things to Josh and David, or was your experience a little different?

Karen Firestone: (03:11)

Yeah. It's interesting to refer to it as pain points because I definitely feel that on March 17th in Boston, happened to be my birthday, when they closed the city because it was St Patrick's day and they said, "Everybody now, no restaurants, no bars, go home." It was painful to suddenly realize that we weren't going to be able to see each other. My office had not been virtual in the sense that Josh's, we worked together in the financial district in Boston, and that comradery was a big element to the company. And what we felt was sort of our cohesiveness and our clients often would come in... We have clients all around the country. We have clients in other countries, but we saw them frequently and we would talk to them sometimes. But coming into the office was something that they seemed to enjoy, or going to visit them. And suddenly having none of that and people working virtually was something to adapt to. We had the technology for it. We were all ready to do it. We had been using Zoom a little bit. We began obviously to use it all the time.

Karen Firestone: (04:22)

I found that... I have two very active dogs who were scratching on my office door at home. I said it's very hard for me to work here. And I began to ride my bike into downtown Boston every day, and there was nobody on the streets. There were no cars and there were no people when I got downtown. So I was in the office, I said, I'll open the mail. I can do wires. I mean, hadn't done anything like that for years. But I was there... Everybody was at home and we just progressed and we had to learn how to connect in a different way. That I think has been hard. Some people prefer to be in an office, prefer to talk to each other face-to-face, the clients or my colleagues.

Karen Firestone: (05:05)

I don't know if there are people who really work better in a sort of close knit relationship type environment, work better when they're not in the office. Yeah, there are some people who might, but it's hard to have that type of camaraderie, spontaneous discussion about investing as much when you can't sort of grab people, "Come on over into my office or into this conference room and let's chat about an idea." So that has been a part of what we've missed and part of the pain, but we've done well. We persevered. We started to come back. July six when everyone was vaccinated, that's when everybody was welcome to come back. And there are many days that everyone is back and some of the people or partners with small children have been home more, and some clients have asked if they would be able to come into the office. I think it's more a social thing, they're not seeing anybody so we're somebody to see, which we like. We hope it's fun for them.

Karen Firestone: (06:12)

But it's been a big adjustment. We can do it virtually. I don't think it's as much fun and this will change, of course, the way in which we do business forever, I think.

Sean Allocca: (06:27)

Sure. Interesting. So I think that's a good segue into another question that David kind of pointed to as well, which is when do we bring back employees into the office? Wall Street has postponed their plans, although they're pretty adamant that they want to get butts back in seats. Some of the other firms have been a little more lax about it and have a little more ability to work from home. What are your thoughts? What are the pros and cons? Do you want to start off, David? I knew you had a interesting take.

David Bahnsen: (06:53)

Yeah. But look, I have really strong opinions on it. I wrote an article in the New York Post last summer, and I sent a letter to the CEO of 25 firms in New York. A couple of them responded to me. I feel-

Josh Brown: (07:06)

I've been meaning to. I will.

David Bahnsen: (07:06)

Yeah. Josh and I had a great interchange on it, and there was some cussing and... No, look, the fact of the matter is, I think every firm has their own problems to solve. It's a lot easier... My firm now has 35 employees. When you're talking about JP and Goldman, so forth and they have hundreds of offices, let alone tens of thousands of employees. I think JP's case, it might be a million employees. I'm kind of more old school in the way that apparently Mr. Diamond and David Solomon are about this. But to the extent there's some that feel differently. I get it. It's just, I do believe I've built the firm around a certain culture and so that brand matters. And I think Karen's alluding to some of this, the inner action in the office is important for us.

David Bahnsen: (07:53)

I've also spent a long time in my career in branches. I was a managing director of Morgan Stanley for many years, and I never talked to anyone in the branch. First of all, they were all gone by two o'clock every day, I never saw them. And I got to know the people at our Chairman's Club trips more than I got to know the people in my own office. So the branches not reopening, might be a different story in the wirehouse world, but for us, it's an important thing. So my strong opinions are specific around what I believe about my company, but then also what I believe about supporting the cities. I couldn't stand seeing Manhattan last year with the coffee shops, and the dry cleaners, the laundromats, the bars, that type of thing, what it was doing economically to the city, I thought it was awful. And I wanted to see the big employers bring people back to support the infrastructure of the city. And I hope that, that will be expedited now here, post-vaccine. That's my take on it.

David Bahnsen: (08:45)

If I keep talking, I'll say something I'll regret.

Sean Allocca: (08:50)

How about you, Josh? I mean, you guys have been across the country already, right? So you have to take on mandatorily bringing back people to office, or...

Josh Brown: (08:56)

No, we're not mandatory. We kept the office open last summer like David did, but for a different reason. I was not there, but I have many millennial employees living in Manhattan and Long Island City in Brooklyn, and they don't want to be confined to a 1200-square foot a room all day. And so we had a clean, air conditioned, 5,000 square foot space on Bryant Park. They could get in, they could get out. They could be there with three other people and just hear someone else breathing, right? Like that stuff is meaningful, I think, just to have somewhere to go. A lot of these people... It's a 100 degrees outside in Manhattan in the summer, so you can only spend so much time out the element. You need a second space that's not your house, and all the Starbucks are closed.

Josh Brown: (09:48)

So I said, let's just reopen. I'm not worried about the liability. I don't think we're going to have a super spreader event with three kids sitting at laptops. So that's why we reopened and I've kept it that way. And what I've noticed.... Every week I go in on Thursday, we do a podcast, YouTube video there, we have guests, we made it vaccine mandatory to visit the office, whether you work here or not. But every week I see more people that work for us, and I even see people that work for us in other states, visiting New York just to spend a few days at the headquarters and just see each other. So I agree with what everyone said about, there is something important culturally about getting together in person. I just think we have to be realistic, the genie's out of the bottle and nobody is thinking, "I'm going back to exactly the way things were", especially people taking the Long Island railroad like myself every day.

Josh Brown: (10:51)

So here's one of the lesson I want to say, and this-

Karen Firestone: (10:54)

No, impossible.

Josh Brown: (10:55)

Yeah. Probably not.

Josh Brown: (10:56)

... this applies to client meetings too. It's not that no one's ever going to want to be together or meet, it's just that when we do do it, it's going to be really meaningful. People are really going to appreciate it. When you go see a client, now it's not obligatory. Now it's an event let's do lunch and we'll spend the first 30 minutes, "What vaccine did you get? I got Pfizer. Oh, I got..." We'll all do that, but so what? It's going to be like a powerful moment that you actually put on pants and left the house for me.

Karen Firestone: (11:27)

[crosstalk 00:11:27].

Josh Brown: (11:27)

So I think, on the whole, it's going to be a positive thing because now we're going to appreciate each other and each other's time more than we used to when it was just taken for granted and obligatory.

Josh Brown: (11:40)

Little applause for that. What's up? I appreciate you guys.

Sean Allocca: (11:42)

I felt it. I was feeling that.

Josh Brown: (11:42)

Happy you do feel.

Sean Allocca: (11:46)

You said Long Island railroad... New Jersey transit's probably way worse, but similar situation, so.

Josh Brown: (11:50)

It all sucks. Right.

Sean Allocca: (11:52)

Yeah, in both states, subsidized.

Sean Allocca: (11:55)

How about we switch gears a little bit and talk about maybe portfolio management and see if there's any trends or things that we saw there. It's been a-

Josh Brown: (12:06)

Did anyone mention crypto with this conference yet?

David Bahnsen: (12:07)

I haven't.

Josh Brown: (12:08)

Has that come up?

Sean Allocca: (12:08)

We're trying to stay away from it.

David Bahnsen: (12:10)

They have a breakout on it tomorrow.

Josh Brown: (12:11)

Okay.

Karen Firestone: (12:12)

Yeah. But I'm wearing something, so.

Josh Brown: (12:13)

I won't spoil it then.

Sean Allocca: (12:16)