The Future of Private Markets with David Rubenstein, Co-Founder & Co-Chairman, The Carlyle Group. Jeff Blau, Chief Executive Officer & Partner, Related Companies.

Moderated by Matt Brown, Founder, Chief Executive Officer & Chairman, CAIS.

SPEAKERS

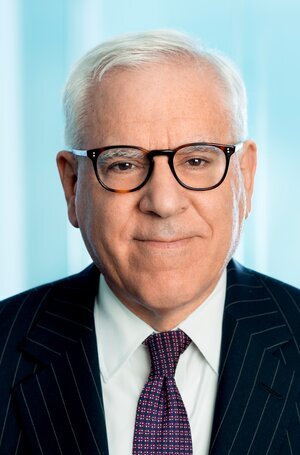

David Rubenstein

Co-Founder & Co-Chairman

The Carlyle Group

Jeff Blau

Chief Executive Officer & Partner

Related Companies

MODERATOR

Matt Brown

Founder, Chief Executive Officer & Chairman

CAIS

TIMESTAMPS

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

Matt Brown: (00:07)

David, Jeff, welcome.

David Rubenstein: (00:10)

Thank you for having us.

Jeff Blau: (00:11)

[crosstalk 00:00:11].

Matt Brown: (00:12)

My name is Matt Brown. I'm the founder and CEO of Case. I'm really honored to be with two great business leaders in the private market space. David Rubenstein, Jeff Blau. We have a somewhat limited window here, 35 minutes, but I don't think either need a big introduction, but I think we would love just to have you each to spend a second introduce yourselves and we'll dive right in.

Jeff Blau: (00:39)

So thank you for having us today. So I'm Jeff Blau, I'm the CEO of Related Companies. For those of you that don't know, we're a large real estate development company based here in New York City, right across the street. You might know the Hudson Yards that we built and own as well as Columbus Circle, which is now called Deutsche Bank Center, used to be Time Warner Center. Across the country, we develop in most of the major markets throughout the US, and then London outside. We employ about 4,000 people. Today one of the largest real estate development companies in the United States.

David Rubenstein: (01:15)

Okay. I'm David Rubenstein. I'm the co-founder and co-chairman of the Carlyle Group which is a global private equity firm operating in 35 different cities around the world. And we manage about $276 billion currently. And we are actively investing in this environment and we think it's a pretty attractive environment in many ways.

Matt Brown: (01:37)

Great, welcome. Today's panel creating value and democratizing access in a post pandemic world is our title. I think with David and Jeff, we could take this in a lot of different directions. So let's just kick off. The last decade has been just astronomical in terms of private markets growth, both on the real estate side, Jeff and David on the private equity side. Let's just talk about some of those drivers. What's going on in the environment that's propelling your areas for just such extreme growth?

David Rubenstein: (02:08)

Well, the charm and good looks of the founders of global private equity firms has probably been the principle driving factor would be my guess, but if you don't believe that, the returns have just been better than any other asset class. Private equity over the last 10 years, 15 years, 20 years, 30 years and so forth, and almost every year outperforms public equities by 300 to 500 basis points depending on the year and the [inaudible 00:02:31] and so forth. So people have consistently said, well, if I can get better rates of return, I should do that. Now I have a higher risk factor, but over the years, people have included that private equity and its various forms buyouts, venture capital, growth capital, infrastructure is not as risky as was thought to be the case 30 or 40 years ago. So if you don't have the high risk that people thought you had in these so-called alternative investments, and you're going to get a higher rate of return, people are willing to pay the higher fees involved and willing to have the longer holding period.

David Rubenstein: (03:01)

So that's basically what's driven is that the rates of return have just been more consistent and the industry is much more mature in the sense that the people in the industry are more sophisticated about avoiding bad deals and even though we're paying reasonably high prices by normal standards, the industry has so much more talent to make these companies work than it did 20 or 30 years ago. And I think people feel much more comfortable than they did 20 years ago in investing in this area.

David Rubenstein: (03:26)

20 years ago and obviously 20 years ago was a tragic occurrence right near in this site where we are today, 20 years ago, you had less than a trillion dollars invested in overall private equity, all assets [inaudible 00:03:41]. It was less than a trillion. Then you're all over private equity is probably eight to 9 trillion. So it's gone up dramatically in this 20 year period of time. And I think the rates of return have been very, very consistent and people believe they will be consistent in the future. And because interest rates have been low, it's been driving people to get out of traditional, fixed income kind of investments. And they go into things that are going to yield better than the low things you get on treasury bills or other corporate bonds.

Matt Brown: (04:07)

Jeff, what about the real estate world?

Jeff Blau: (04:08)

So I would say similar to private equity, if you think back 20, 30 years ago, real estate was never really considered an institutional asset class. And so spreads were wide and it was a lot of inefficiencies in the market over this period of time. People have institutionalized private investment in real estate assets, whether it's opportunistic investments through development acquisition, or even more recently, some of the very, very large core funds that have been created really as interest rates have come down so low, the spread that you can make owning real estate is greater than almost any other point in time.

Jeff Blau: (04:45)

And so there's been huge inflows into core ownership of real estate, providing steady recurring income, cash flow, and tax benefits to investors. And so if you look at it today, it's a much more institutionalized product and capital flows are really greater than they've ever been into the real estate sector.

Matt Brown: (05:04)

Just staying on that, we've been through a pretty dramatic 18 months. Different businesses have succeeded. Others have turned the lights off. They always do this when I start talking, by the way, I should have told you that. The COVID-

David Rubenstein: (05:21)

Actually, maybe our time is up already, I don't know.

Jeff Blau: (05:24)

Now we can see everybody.

Matt Brown: (05:26)

Anthony Scaramucci just wants to see what we're made of, I think.

David Rubenstein: (05:28)

Okay.

Matt Brown: (05:29)

See? I can see him with a little light switch. Jeff, the pandemic, the global pandemic has negatively impacted so many companies on the flip side. So many have been beneficiaries, specifically around the real estate industry and directly related. Walk us through kind of what the last 18 months have been for you, how you reposition the firm.

Jeff Blau: (05:54)

So I would say COVID has really thrown everything for a loop. It's been the wildest swings I could possibly imagine in the past 30 years in real estate. You almost saw this vacuum of people leaving cities, the core urban markets, apartment buildings emptying out, retail stores going out of business. People really even today aren't back as much in their offices.

Jeff Blau: (06:20)

And yet you look at the last 60, 90 days, you're seeing a complete reversal of that trend. So to give you some high level numbers, we own one of the largest apartment portfolios here in New York. So at its absolute peak, that portfolio went from 98% occupied to 83% occupied. In order to get people to sign leases, we were giving away three months rent. That portfolio is back to 99% occupied with no free rent. So basically we're kind of even plus 1-2% to pre COVID numbers. So that's been a remarkable swing and really, I think that's been around this timeframe, Labor Day, September, back to school, I think the Delta variant has put a little bit of a damper on return to office, but still, I think there's been a huge inflow of population back to the cities.

Jeff Blau: (07:12)

Now, condo sales have picked up again. We've had actually the last 60 days have been the most robust condo sales since 2013 here in New York. S we have seen a tremendous swing. It's been a pretty wild ride. I would say the other thing that's happened is people have further rediscovered what we would typically have called secondary cities. So our offices are in New York, Chicago, LA, San Francisco, Boston, DC. And that's where we've been most active, but there are great cities and we've always been small investors, but now have become much larger in Austin, Charlotte, Denver, West Palm beach. These were markets that we had typically called secondary, and I think there's been a lot more interest in those cities and think they'll really become primary markets for many people.

Matt Brown: (08:03)

Same question to you. I just want to ask one more question, but Jeff, a lot of people say, when will Manhattan be back? Being here in Manhattan. And of course back is a bit in air quotes. When is Manhattan back?

Jeff Blau: (08:14)

I do think a lot of Manhattan is back. If you just walk around... First of all, you can't get a reservation, you can't go out to dinner. The restaurants are packed and the West Village is packed. The meatpacking district is crowded on a Saturday. So New York is feeling like it's coming back. I would say the only thing that is not really back here are people's return to the office. And I think that's something we can talk about, but I think that's going to change a little bit over time and that's going to be a slower return.

David Rubenstein: (08:47)

For the country as a whole, the pandemic has been a tale of two cities. If you are uneducated, you work with your hands, you can't afford childcare, you don't have broadband, this has been a terrible time for you. And you've fallen further and further behind than where you were before. If you're in the financial service world and everybody here presumably is, this has been a pretty good time. The private equity world has done more deals, exited more deals, raised more money than any other time in its history. So if you'd flown in from Mars and said, okay, a pandemic is going to strike the entire world and particularly the United States where we've lost 650,000 people, how can the private equity world do so well? Well, there's lots of reasons for it, but technology enabled us to basically raise money, invest money, and exit deals and do road shows for IPOs and things like that without having to actually physically go anywhere.

David Rubenstein: (09:41)

So it's been amazing. And the question will be going forward, will people want to physically go travel around the world to raise money? Will people want to physically go on road shows again, the way they used to on IPOs, as opposed to doing virtually? Nobody knows the answer to that for sure. I suspect it'll be some homogenized kind of view of what will happen, but the private equity world could not be honestly in better shape. The hardest things in private equity right now are if you're a first fund. People don't like to put money into a first fund, unless they meet you in person, appropriately so. There's a due diligence standard. You have to meet the person.

David Rubenstein: (10:14)

So if you're raising a first fund, it has been more challenging now in this environment. But if you're raising a third fund, a fifth fund, an eighth fund, you can get your re-ups done if you have a reasonably good track record very, very quickly. And if you're doing deals, it saves a lot of wear and tear. You don't have to travel as much. So it's been a blessing in disguise for people who are in the financial service world. For people who are not in that world, the people I referred to earlier, this has been a terrible situation, and it's not going to get any better anytime soon, because we still have less than 35% of the people are not vaccinated yet. And that isn't probably going to change anytime soon.

Matt Brown: (10:51)

David, why would this great change in behavior to our benefit, virtual communication, the change in behavior, virtual communication now is stepping in-

David Rubenstein: (10:59)

You mean going forward?

Matt Brown: (11:00)

Yeah. Going forward.

David Rubenstein: (11:02)

Well, going forward, people are used to, let's say doing Zoom meetings now, but I think there's a feeling that once you can travel, probably you should reconnect with people. There's nothing quite like a personal connection which you can get when you're having lunch or a dinner with somebody or meet them in person. I think there'll be a feeling you should go out. But I don't think people will fly around the world to get a re-up on a fund when they can do it virtually. I think you won't have people traveling quite as much for business travel. I think that's pretty obvious to all of us, but the private equity world's biggest challenge going forward is probably whether prices are going to be so unattractive because they're so high that people feel compelled to do deals because they have a lot of money.

David Rubenstein: (11:46)

And then when the inevitable interest rate rise occurs at some point, presumably after the midterm election, you then see evaluations going down, whether people will run for the exits and say, okay, the great recession is here again. And so people are getting nervous. I don't see that on a rise anytime soon. I don't think interest rates are going to be raised, certainly not before the midterm election. And I don't think we're going to see any big tapering anytime soon, but clearly if we go to a normalized interest rate situation, there'll be some correction for sure.

Matt Brown: (12:13)

Jeff, what behavior has been changed do you think by the pandemic that you see in the real estate world that most likely will not change back?

Jeff Blau: (12:22)

Well as I was mentioning, I definitely think that there's a change in the way people use their office. I think companies, certainly larger companies will continue to have pretty much just as much office space as they have today. But I think there's going to be a lot more flexibility around how it's used. And I think whether it's four days a week or three days a week, I think companies are going to have to offer as a concession amenity to attract employees that flexibility in the workplace. Yet, when I talk to the heads of some of the big tech companies that say, oh, we can go remote, they will privately acknowledge that they really can't have culture creation, productivity, and innovation at home on Zoom.

Jeff Blau: (13:06)

And so what they're really trying to do is figure out how they coordinate this flexibility in the office. So maybe a whole group has to come in all the same four days or three days so that when they are in the office, it's much more of a collaboration effort that's happening. And that may help. That may force us to redesign how spaces are built out. There might be more meeting spaces, more gathering spaces, fewer private offices, but ultimately people are going to need to get back to the office and we're seeing it now in corporations actually taking more space in anticipation of all the growth that you just talked about, even though there's going to be that flexibility in the workplace.

Jeff Blau: (13:48)

And then the other thing David touched on, I do think that there will be some permanent changes in business travel. I think leisure travel people absolutely want to get back and leisure travel business has been unprecedented over the last 90 days as people felt a little bit freer to get out of the house, but we haven't seen the same levels of business travel yet when we had 2,500 people here today. So I think that's a great test to people gathering and getting together and staying at our Equinox hotel at Hudson Yards. Thank you for those of you staying there. And so it will be back, but I think business travel will be a slower recovery than the balance.

David Rubenstein: (14:30)

Great events in history tend to take a long time to have an impact in the way people live and work. So the industrial revolution took roughly a hundred years before people really changed the way they lived and work and became more of an industrial economy, an urban economy than an agricultural economy. The things we've lived through, it took maybe 25 years for the internet to really change our lives. It took smart phones, maybe four or five years to change our lives, social media, two or three years. In basically 18 months, we have changed the way we have we're going to live and work considerably. Yes, people are going to come back to the offices, but probably not five days a week and quite the way they did before. And people aren't going to travel quite the way they did before. So we've changed the way we live and work.

David Rubenstein: (15:11)

And those people that adapted this well are going to be quite successful. Private equity people tend to adapt pretty quickly. I think real estate people probably adapted pretty quickly. People in the financial service world adapted quickly, but all of us are fortunate because we have certain skills. We have certain technologies available to us. I think for the country itself, it's going to be a bit of problem before the country can really get back to where it was before for people who are at the bottom of the social and economic strata.

Matt Brown: (15:37)

David, many investors in the audience. We hear the word bubble when we think about private equity now, real estate. Most people don't believe there is a bubble. Where do you come on the private equity bubble that everyone seems to be hinting at?

David Rubenstein: (15:55)

Sir Isaac Newton, one of the smartest men who ever lived, he invested in the South Sea Corporation and he got out before it peaked. And he was upset with himself. He said, I'm a genius, but how come I got out and stocks still going up? So he went back in and ultimately was a bubble collapse. So people have a temptation to feel that they're missing something great. And so that's why people are still investing pretty heavily. They're afraid that they're going to miss something great. And maybe they will miss something. I think people have to be cautious, but you never know you're in a bubble until it's over. And as soon as we go into the next bubble and there's a bubble in some area and I'll think all of a sudden people will come out of the woodwork with their memos saying, well, I told you this. Of course, these memos were filed away.

David Rubenstein: (16:40)

They weren't given to people at the time or they weren't made public. People always were saying they predicted a bubble. Right now, I don't think we're in a bubble. Clearly, we're not in the kind of bubble where we had the 1999, 2000 internet bubble. They were kind companies with no earnings, no revenue, virtually nothing and that they had high valuations. I don't think that's quite the case today. The valuations are a bit high in some cases for some growth companies. But I do think that they are transforming the way we live and work in ways that I think we will grow into those valuations. So I don't think we're in a bubble, I'd say Palm Beach, real estate might be in a bubble in some cases, and maybe South Hampton and East Hampton real estate might be in a bubble. But generally I wouldn't think we're in a bubble of the type we have to worry about the way I felt we had to worry about things in 1999 or 2000.

Matt Brown: (17:27)

How would Carlyle reposition right now if you actually believed you were in a bubble? What are some of the immediate at things that you would be doing?

David Rubenstein: (17:35)

Well, it's difficult to talk about that because I'm afraid I'll be misquoted in saying that we are in a bubble. I don't think we are in a bubble, but if you were in a bubble, you would obviously slow down the amount of money you're putting out and people are putting out records amounts of money. People are afraid they're going to miss the next great thing. So anybody who thinks they're in a bubble should obviously slow things down, but go back to the companies you've already invested in and see whether they have debt that can tolerate some kind of slow down in repayment. Obviously most of the buyout deals today are done with covenant light debt, so it's tougher to default than it was 20 years ago. And so I think that people are much more experienced in dealing with downsides than they were 10 years ago or 20 years ago.

David Rubenstein: (18:19)

So I don't think we're in a bubble. There might be in certain sectors some people are too anxious to put money in some things. So some people would say cryptocurrency is a bubble. I don't subscribe to that view necessarily. I don't own any cryptocurrencies, but I know there are some people and people I've interviewed recently have said, yes, this thing is all going to zero. But of course, when am I going to go to zero? Who knows how long it's going to take. I would say cryptocurrencies clearly have a market. And I would not bet against it because I think that would be difficult, but at some point probably some of the air will come out some of the cryptocurrencies, I just don't know which ones.

Matt Brown: (18:55)

Jeff, speaking of West Palm beach and Palm beach, where I know you view that as a secondary city. I was there recently and I think I saw a property smaller than my first Manhattan apartment asking some of the neighborhood of 10 or 12 million dollars. What's going on down there? And same question to you. I know you don't believe we're in a real estate bubble right now, but tell us what's going on that space.

Jeff Blau: (19:20)

Right. Well, I think you have to separate out some of the very unusual special spots like Palm Beach, Hamptons, Aspen in terms of single family home prices that have really escalated during this period of time and then the institutional investment world in which many of us operate. So if you talk about the institutional investment world, I don't think that there's a bubble there in real estate either.

Jeff Blau: (19:45)

I think people are investing in real estate, essentially one of two ways where one is an opportunistic invest where we've been very successful over the past year investing in situations that have found themselves in trouble because of COVID. And we've been able to put out a lot of capital in that space through opportunistic investing, but really where the tremendous capital flows are now is a result of low interest rates. All right. And so you have to have a view on interest rates to determine if you think we're in a bubble or not, but people have been looking for alternatives to essentially 0% returns. And so investing in stabilized core assets and getting that spread in core real estate has been a great investment over the past several years. And I think you'll see that continue into the future. With regard to West Palm beach in particular, we have been very, very active in that market for a long time before COVID and I'll say unfortunately, maybe for New York, but it's good to be on the receiving end.

Jeff Blau: (20:53)

We've seen a lot of people move businesses, mostly smaller financial service firms, family offices, to Palm Beach. People have moved, put their kids in school down there and have taken office space and today we really control almost the entire class A office market in West Palm beach. And that has completely filled up over the last 12 months, as I said, mostly people from here. And so we are monitoring that shift back and forth. People typically aren't moving their businesses completely, but opening secondary satellite offices. And interesting in many cases also expanding here in New York at the same time. But West Palm has been, has been terrific.

Matt Brown: (21:40)

Qualified opportunity zones are somewhat the opposite of Palm Beach in many ways. That's an area of focus for related, maybe a quick brief description on the QOZ opportunity itself. And then how are you focusing on it at Related?

Jeff Blau: (21:56)

Sure. A qualified opportunity zone is an area designated by the federal government to encourage development in those areas or to encourage businesses to move to financially depressed neighborhoods by zip code. And essentially what it does is it allows you to sell an asset, whether it's a corporation, shares of a company, or a real estate asset, and reinvest that gain into something, real estate development, a new business in a qualified opportunity zone area, and you can defer the taxes on that gain until end of 2026. And then even when that tax comes due, you only owe 85% of what would have been due back then. And then the money sits invested for 10 years and all the earnings during that 10 year period is not taxed at all, has no tax on it. So it's been a great opportunity for people to move money from gains that are sold into qualified investment opportunity.

Jeff Blau: (23:02)

And we have made a business of investing in real estate assets, typically new construction development assets in qualified opportunity zones. So raising money from individuals, placing that money into qualified opportunity zone real estate developments, and then we hold and manage those assets to maturity at the end of the 10 years, at which point we'll sell those assets and return the capital on a tax deferred basis for the investors. So it's really been a great product and really has created a lot of investment in those areas throughout the country.

David Rubenstein: (23:37)

I personally invested in a large one associated with the Boston Housing Authority.

Jeff Blau: (23:41)

Should have gone into our.

David Rubenstein: (23:42)

[crosstalk 00:23:42].

Jeff Blau: (23:42)

You didn't come into our funds?

David Rubenstein: (23:44)

I didn't go into a fund, I did it directly, but-

Matt Brown: (23:47)

You can access his fund in our platform if you want.

David Rubenstein: (23:49)

But I do think that it has potential to be very attractive, but I didn't do it because it was the tax consideration because to qualify for the task consideration, sir, it's complicated. And obviously as you know, it doesn't work for everybody. On the other hand, there are some good investments in these areas, whether or not you take advantage of the tax zones or tax opportunity or not. But the lesson I wanted to talk to people about is this, very few people knew about this in the Trump tax cut. It was lobbied through by Sean Parker among others, and it was done, I would say relatively quietly, at least for the general public, when the bill was passed, people saw it was in there. You're going to see the same thing in this current tax bill.

David Rubenstein: (24:34)

We're not going to know what's in the tax bill until it passes. The tax bill probably won't pass until the last day in Congress or so. And at that point I suspect there'll be a lot of things in there. So look for lots of investment opportunities or tax advantaged investments opportunities in the new tax bill. I don't know, who's lobbying them through at the moment. I'm not, but there will be some in there because every tax bill has surprises just as this one was a surprise to many people in the investment world.

Matt Brown: (25:01)

David, speaking of the US government regulation, there's always been that delicate dance between the private equity titans and the SCC and the US government trying to regulate. What's the state of play right now? Is the government helping grow the businesses? Are they worried about oversight?

David Rubenstein: (25:21)

I think the government of the United States has a lot of challenges right now and I don't think their biggest challenge is trying to figure out how to make private equity do things that it's not otherwise doing because of market forces. So we have not been anybody's sites relatively speaking. And so there might be some changes in the tax bill that might affect private equity, but generally people in Washington are more worried about regulating cryptocurrencies or other things and not private equity in part because we haven't had a lot of things that attract attention.

David Rubenstein: (25:49)

When you have a lot of bankruptcies, that attracts attention. People lost a lot of money, that attracts attention. That hasn't happened in private equity for a very, very long time. And as a result, I think private equity is not something that the administration is focused on or Congress is focused on. There may be some modest changes, but generally I don't expect big changes coming out of Washington in the regulatory or legislative area that's going to affect adversely the private equity world.

Matt Brown: (26:13)

One area that the US government is being quite proactive in is trying to allow more and more individual investors to gain access so they're actually on the side of the individual investor.

David Rubenstein: (26:21)

This is an important point. If you are a graduate of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, any great school, and you majored in finance and you're brilliant, but you decide to go to work for Teach for America and you make a modest salary. You're not an accredited investor. If your father is really rich and you flunked out of a couple colleges, but he gave you a hundred million dollars, you're accredited investor. So you can then do whatever you want with that money. It does seem a little ass backwards that the person who needs the higher rate of return that private equity might give you can't get it because he or she is not accredited.

David Rubenstein: (26:55)

Whereas the idiot who has a lot of money, he can go do what he wants or she can do what you wants. So it does seem strange. And finally, I think Washington is raking up to this and they are going to do things that are going to make it easier to democratize private equity for people that probably can benefit from some of these higher returns that are available in this industry. And I think you'll see 401k checkoff plans and other kinds of things that people will be able to do regularly get into various private equity areas. There's some challenges, but I do think five years from now, 10 years from now, almost everybody that wants to be in some type of alternative investment can do so even if you're not wealthy.

Matt Brown: (27:30)

I think that's right. I think at least the background there is that they wanted you to have enough money that you could lose the capital and not be impacted. So they're effectively saying that these asset classes are overly risky. That narrative has completely changed. And now they're opening it up. Jeff, when you think about product development and new funds that you're launching, do you think about the wealth management community or the individual investor and fund structures and strategies that make more sense for them?

Jeff Blau: (28:01)

So this has been one of the big shifts over the last couple years into real estate, where most of our investors have been historically institutional investors. You're now seeing more and more individuals come in through aggregators and some of the big real estate private equity firms, Blackstone, Starwood have taken the lead on this. We're doing this now at Related in terms of going to start raising capital through wealth management channels for debt. And these more core type investments that we've talked about. Your firm has been very active on aggregating capital from investors, individual investors, and investing into funds that were typically only open to institutional investors. And so I do think there has been, as you said, democratization in real estate and that has attracted tremendous capital flows.

Matt Brown: (28:50)

What's driving the demand, David?

David Rubenstein: (28:52)

Well, interest rates are so low. So people don't get the kind of rate of return that they normally would want from their fixed income investments. People see other people making money and so they get jealous and they say other people money, they're not smarter than me, why can't I make money as well? And the returns have been pretty consistent and the RIA market is gigantic. I spoke this weekend on Saturday to a group in Kansas City, several thousand people in an RIA group. And it was one firm. And every time I go to make a speech in front of large audiences these days, it's generally terms of groups of large RIA groups that have aggregated are one firm. There's an enormous amount of money in the RIA world. And the RIAs are increasingly feeling that their clients are going to be well served by putting money into some private equity firms.

Matt Brown: (29:41)

Well, Carlyle has done a great job on that. And just some numbers behind that, the RA channel advises between 10 and 12 trillion dollars in assets. That's excluding of course the larger wealth management firms like Morgan Stanley and Goldman, JP Morgan, just the RIA channel. Average allocation rates in the RIA space to alternatives are about 2%, so if you just project out what a 15, 20% allocation to alternative investments, whether it's real estate or private equity, we're now looking at a multi-trillion dollar jump all for the firms that want to be there.

David Rubenstein: (30:14)

Well, when private equity... It was in 1978 when the US government and, and Department of Labor said that ERISA funds could finally go into private equity or alternatives, and then Oregon and state of Washington, others went in and then they began having big allocations. And now you see typically for endowments, pension funds and so forth allocations somewhere between 15 and 20, 25%, in some cases, even 30, 35% to alternatives. The RIA channel isn't as high as that right now, people aren't putting as much in as higher percentage, but it will drift up to a higher number to reflect what I think the institutional market is recognized that the risks aren't as great as people thought, and the returns are much better than people thought.

Matt Brown: (30:54)

Jeff, there's this rise of the do it yourself investor. We're seeing it with Robinhood and Betterment and so forth. Now we're bringing serious institutional products, investment strategies into that market for the first time, which we all think is a positive. Who has responsibility for education or oversight to make sure that there's the right suitability in place? Is that now going to be put... If the SCC in Washington is loosening, that going to be pushed onto firms like you if we open up the channel for every individual to come in?

David Rubenstein: (31:30)

Well, my hope is that that people will feel they can write things in language that's understandable. Unfortunately, we now have a lot of legal documents that are very difficult for people to understand. I hope, and as we move forward, the things that educate people are going to be written in relatively simple English so that people can understand what they're really investing in, but particularly what the fees are and what the risks are. Sometimes if you read a prospectus, you really have a hard time figuring out what you're really getting into. So if the government of the United States does anything, I hope they will do a better job in educating people about the risk in simple English and the firms like ours have a responsibility to do that too. So I do hope that both sides, the firm that's doing the investing and the government will require people to really read something that's understandable before they go into some of these investments.

Jeff Blau: (32:24)

I also think it's you do have the wealth managers now in the middle of that. So there's one more group that's actually selling the product to the investors, whether it's a company like yours, or Morgan Stanley that is basically interacting between our documents and the individuals. And I think it's part of their responsibility to make sure that everything is explained properly.

Matt Brown: (32:47)

Do you think it's unusual that we can all board an airplane with an identification code that says you're a TSA, you're not a bad guy, but we still have to photocopy a picture of our driver's license to invest in a Blackstone fund and every other fund? When is innovation going to catch up here and just make this a little easier for people, because if you hope to attract the individual investor, it has to be simple and easy, understandable, but technology and speed and seamlessness has need to come into play here.

David Rubenstein: (33:18)

Well, I think that that is happening. And I think the technology world is such that now people are inventing things that'll do things like that and make it much easier so that you can invest in these kind of funds without having to fill out so many forms that you really can't understand or that take forever to get done that discourage people from doing it, but in the end, there's no such thing as a risk-free investment. Everything has some risk. I just think that people should be allowed to take a little bit more risk than maybe they're allowed to take today if they want to get higher rates of return other than what they've been doing and just putting things in treasury bills or something like that.

David Rubenstein: (33:51)

And the world's moving in that direction. And it's not just in the United States. Today, I would say roughly 60% of all private equity investments is still in the United States. So as the world moves forward and gets wealthier, you're going to see much more private equity and alternative investments in Europe and so-called emerging markets. It's going to take a while, but I do think at some point, you'll see the United States, not quite as dominant in the private equity world in the alternative world, as we currently are.

Matt Brown: (34:16)

Jeff, if you had to allocate a hundred dollars of your personal capital and limited to three buckets of investment strategy, either within the related umbrella or not within real estate, how are you waiting that right now, going for the current market and going forward?

Jeff Blau: (34:34)

I think about that all day, because that's where my money is allocated. But I would say you want to have a fair amount in opportunistic real estate assets because that's where you're going to get higher returns. But you also want to make sure that you have a bit of a nest egg and get current income and that's core. So I don't know, maybe I would probably be 60 to 70% and opportunistic in the balance [crosstalk 00:34:58]

Matt Brown: (34:58)

And what percent of an individual or an institutional portfolio should have real estate overall?

Jeff Blau: (35:04)

I think the pension funds today, you try to target between eight and 12% in real estate.

Matt Brown: (35:12)

David?

David Rubenstein: (35:12)

I would say that the greatest pleasure that you're going to get from investing is investing so you can give some of that money away. So I encourage all of you to think about your own philanthropic interests. All of us have thought recently in the last couple weeks and certainly in the last couple days about this country and some of the tragic times we've been through. And I think if people who think about what they can do to make this country better and give some of their money that they make from investing in real estate or private equity to things that I think makes the country better, I think you're going to feel much better about that.

David Rubenstein: (35:44)

And so I hope everybody here can just ask themselves, what are you doing to make the country a better place? What are you doing to give back to this country that made it possible for you to be as reasonably wealthy as you are? And I think when you find that thing and you give some money to it and give some time to it, you'll feel much better than even if you get a triple or quadruple on one of your investments.

Matt Brown: (36:03)

We're almost at time. I just want to ask you one last question each. You've both built and run great businesses. A lot of young people coming to work for you, with you, learning. If you were mentoring a young employee or an entrepreneur, what's the one piece of advice you'd give them?

David Rubenstein: (36:22)

Have intellectual curiosity, ask questions, read. You can't read too much. Learn how to write, learn how to speak, learn how to get along with people and have some humility about what you do if you accomplish something, because you'll get much further if you're humble. You'll get much further if you actually have intellectual curiosity and try to make yourself valuable to any organization you're in. Make certain that you're actually adding value. Specialize in something, know it well, and then help other people with their projects. As Ronald Reagan famously said, there's no limit to what humans can accomplish if they're willing to share the credit as well.

Matt Brown: (36:57)

Share the credit. Jeff?

Jeff Blau: (37:00)

I would say you have to pursue an area that you're passionate about. You have to enjoy what you do every day. And going back to what David said about philanthropy, a good portion of what we do all the time is focus our efforts on affordable housing development, because we think it's one of the most important things that we can do for cities and this country needs. And so being able to pursue a passion of mine, which is real estate development and being able to do that in an area where we're also doing good for society, I think that's really, that's the perfect career. And if you can position yourself that way, that's the best outcome.

Matt Brown: (37:35)

David, Jeff, thanks so much really enjoy it. Really appreciate it.