“You’ve got to give them a sense of respect when we talk about essential workers, about farmers, about people in construction, about people who are working in mines.”

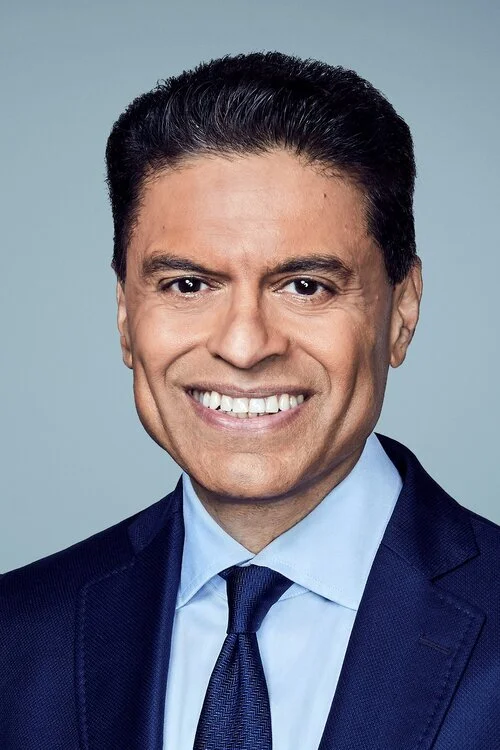

Fareed Zakaria hosts Fareed Zakaria GPS for CNN Worldwide and is a columnist for The Washington Post, a contributing editor for The Atlantic, and a bestselling author. Fareed Zakaria GPS is a weekly international and domestic affairs program that airs on CNN/U.S. and around the world on CNN International. Since its debut in 2008, it has become a prominent television forum for global newsmakers and thought leaders.

Globalization over the last 100+ years has been responsible for the many of the most important advances in western civilization. Though, in the last 25 years, globalization fueled by an information/technological revolution has created greater inequality with a priority placed on more skilled work. “What's happening is the higher and higher value stuff is being made digitally and operates in a digital world, and the lower and lower value stuff is the physical world… It's more technological than it is globalization and the pandemic has massively exacerbated it.”

We’ve seen the consequences play out in politics and culture where an anti-establishment backlash has emerged. A global economic system designed to move fast was built with few safeguards to protect the working class from the economic seizures we’ve seen nearly once a decade. The key is developing an economic system that balances growth with social and economic security for our more vulnerable populations across the country and globe.

LISTEN AND SUBSCRIBE

SPEAKER

Fareed Zakaria

Host, Fareed Zakaria GPS

CNN Worldwide

MODERATOR

Anthony Scaramucci

Founder & Managing Partner

SkyBridge

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

John Darsie: (00:07)

Hello everyone and welcome back to SALT Talks. My name is John Darsie, I'm the Managing Director of SALT, which is a global thought leadership forum at the intersection of finance, technology and public policy. SALT Talks are a digital interview series that we launched during this work from home period with leading investors, creators and thinkers.

John Darsie: (00:28)

And what we're trying to do during these SALT Talks is to replicate the experience that we provide in our global conferences, the Salt Conference, which we host annually in the United States and we also host an annual international conference most recently in Abu Dhabi in December of 2019, and we're looking forward to getting those conferences resumed here in the near future as soon as it's safe for all of our participants.

John Darsie: (00:49)

At SALT Talks, what we're trying to do is really provide a window into the mind of subject matter experts, as well as provide a platform for what we think are big ideas that are shaping the future. And our guest today wrote recently a great book about these big ideas and these big trends that are shaping our future, some good and some not so good. And our guest today is Fareed Zakaria, and we're very excited to welcome him to SALT Talks.

John Darsie: (01:12)

Fareed is the host of Fareed Zakaria GPS, which is a weekly international and domestic affairs program for CNN Worldwide. He's also a columnist for the Washington Post, a contributing editor for the Atlantic and a best-selling author. Interviews on Fareed Zakaria GPS have included US President Barack Obama, French President, Emmanuel Macron, Chinese Premier, Wen Jiabao, Russian President, Vladimir Putin, Israeli Prime Minister, Bibi Netanyahu and Turkish President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

John Darsie: (01:44)

Zakaria is the author of three highly regarded and New York times bestselling books, In Defense of a Liberal Education, The Post-American Worlds and The Future of Freedom. And then at his most recent book is Ten Lessons for the Post-Pandemic World, which is what we're going to focus on today. Prior to his tenure at CNN Worldwide, Zakaria was the editor of Newsweek International, the Managing Editor of Foreign Affairs, a columnist for Time, an analyst for ABC News and the host of Foreign Exchange with Fareed Zakaria, which was on PBS.

John Darsie: (02:18)

In 2017, Zakaria was awarded the Arthur Ross Media Award by the American Academy of Diplomacy. He was named a top 10 global thinker of the last 10 years by Foreign Policy Magazine in 2019, and EsQuire once called him the most influential foreign policy advisor of his generation. Zakaria serves on the boards of the council on foreign relations of which Anthony is also a member and of New America. He earned a bachelor's degree from Yale University, a doctorate in political science from Harvard University and has received numerous honorary degrees.

John Darsie: (02:52)

Just a reminder, if you have any questions for Fareed during today's talk, you can enter them in the Q and A box at the bottom of your video screen on Zoom. And hosting today's talk is Anthony Scaramucci, the founder and managing partner of SkyBridge Capital, a global alternative investment firm. Anthony is also the chairman of SALTs and he was also President Trump's Communications Director, I believe it was for 11 days. And we're now inside of one Scaramucci until the general election, so that's a big milestone.

Anthony Scaramucci: (03:19)

You're going to get fired, okay? I'm just telling you, keep it up, you're going to get fired, okay?

John Darsie: (03:23)

But Anthony, I'll turn it over to you for the interview while we still [inaudible 00:03:26].

Anthony Scaramucci: (03:26)

Everybody knows Darsie, so be careful, Darsie, be careful. Now Fareed, I'm telling you, we've read that exactly the way your mom wrote that, okay? How impressive is that resume and that background? God bless you. And it's a real honor to be able to call you a friend. And I thought that your book was tremendous. And so, as I'm wanting to do, I'm going to hold up the book, amazing book. Obviously, will go on to be a best seller, but I encourage people to read this.

Anthony Scaramucci: (03:52)

And Fareed said this while we were in the green room, he's written these books so that they can be read in one or two sittings. It'll take five or six hours to read. Probably seven or so hours to listen to in Fareed's voice. And I want to get into it with you Fareed. But before we do that, I asked this question of everybody and I've got to ask it of you. There's something about you that we couldn't learn from Wikipedia or from your television show, and I was wondering if you could share something with us about your life that caused your life to go on the arc that it's gone on in this amazing trajectory that you've had.

Fareed Zakaria: (04:29)

First of all, thank you so much. It's a huge pleasure and I so appreciate the fulsome introduction and the holding of the book. You might've heard this once or twice before, Anthony, but you are a good salesman. You are a very good salesman. To answer your question, look, I think the part that people don't talk about enough, people like you and me who have happened to have had some success in our lives, luck plays a huge part in one's life. And I think we should always remember that. And we should remember that when thinking about people less fortunate than us. There are a lot of smart people out there and there I think that, I meant some important areas, I got lucky.

Fareed Zakaria: (05:13)

But probably when I look back, I'll say the thing that I notice that I think when I look back helped me a lot, was this. My parents, my father was a politician. My mother was a journalist. And in some ways my dad was particularly a traditional dad. I don't think he ever went to my school, for example, in that 12 years that I was in school. But they took us seriously as kids and they shared with us at the dinner table, all the conversations that they would have any way.

Fareed Zakaria: (05:47)

Their friends would come and sit with us at the dinner table. And we would talk about my dad's career, my mom's work, what was going on in India, what was going on in the world. And I got very comfortable with adults, adult conversation and navigating adult life. And I noticed that when I got to college, I got a scholarship to Yale and I got there. And in some ways I was under-prepared. I went to a good school in India, but nothing like the Andovers and Exeters of the world.

Fareed Zakaria: (06:18)

But I think I was better prepared in that one respect. I had a very good feel for how to handle adults and the adult world. And nothing about it faced me, nothing about it intimidated me, because I'd been talking to these people and navigating that life for a long, long time. So I probably feel like that was a crucial advantage.

Anthony Scaramucci: (06:43)

Well, we agree. We agree on providence or the universe offering us luck. There's no question about that. And I think that's apropos to what I'm going to ask you about, because we're an interesting situation. I know you're a student of history. You write a little bit about this in the book and I want you to address your philosophical thinkings about this threading history. The gap is widening Fareed. We can look at the empirical data between the haves and the have nots, or the eventuality of a plutocratic world and then a world that's below the plutocrats which may be suffering.

Anthony Scaramucci: (07:19)

And those people, unfortunately, I'll speak for myself, growing up in a blue collar neighborhood with blue collar parents, we were aspirational, but those very same people are now desperational. And so my question to you is, is this an effect of globalism? Is this is a by-product of globalism? If it's not a by-product of globalism, what do we do to help these people? Because whenever you think of Mr. Trump or the rise of nationalism or populism that exists and systemically it's putting pressure to be reflected into our political leadership. And so I'm just wondering your thoughts on this and how do you think this unfolds over the next decade?

Fareed Zakaria: (07:59)

Wow, that's a great question. It is in some ways the big question, which is particularly in the Western world, how do we sustain this western marvel that transformed the work over the last 200 years, given the very pressures you're talking about? So the way I would describe first of all, to describe the problem correctly, I think that this is fundamentally a combination of globalization and the information revolution. It's not just globalization, because globalization has been going on for a while as you know.

Fareed Zakaria: (08:29)

I mean, we basically begun the big burst of globalization in the 1880s, then the 1920s, then the 1950s. But what has happened in the last 20, 25 years is that you've had globalization, and obviously that means some work goes to lower cost countries. But generally speaking that worked out because that was work people didn't want to do in rich countries. People don't want to make t-shirts for a dollar a piece in the United States anymore. They don't want to make sneakers for $25 a piece. That work migrates and then what happens is what's left in the US and in Germany is the higher value work.

Fareed Zakaria: (09:08)

Some of that has been thrown off by the fact that a lot of the world globalized simultaneously, particularly China and India. And so the effect was faster and more accelerated. But the biggest issue has been the information revolution. Work is now digital, and this is the sense in which the pandemic, as you described correctly, has massively exacerbated this problem. Look, you and I are doing fine because we can work digital. It's a bit of an inconvenience we're doing it this way, we would normally have done it in a conference hall, but that's an inconvenience.

Fareed Zakaria: (09:47)

But think about everybody who works in restaurants, retail, shopping malls, theme parks, hotels, that world has just been devastated. And so what's happening is the higher and higher value stuff is being made digitally and operates in a digital world, and the lower and lower value stuff is the physical world. And of course, that correlates with, do you have a college degree? Do you have technical training? So that's the problem. It's more technological than it is globalization and the pandemic has massively exacerbated it.

Fareed Zakaria: (10:22)

The solution I think has to be two fold. We've got to spend a lot more money on these people to put it very simply. I think we are not even beginning to understand the amount of money we need to spend on things like retraining on the earned income tax credit, so that ... What the earned income tax credit does, it says, if you work full-time in the United States, you will not live in poverty. Whatever the market does, the government will top up your wages so that you do not have to be living in poverty. By the way, it's a great social program. Milton Friedman was in favor of it, so it's a free market program because it encourages work and these people spend that money. So it's actually good for the economy.

Fareed Zakaria: (11:05)

The retraining part is harder, but I'll tell you this, because I've got senior government officials, people who you have to know very well in the Trump Administration came and talked to me about retraining because I've written a lot about it. And they said, "What is your sense of how we learn from the true Germans?" I said, "You want to want the best way to learn from them is, they spend 20 times as much per capita on apprenticeship programs as the United States does." So yeah, there's some clever aspects to the programs, but the number one thing is, they commit real resources to it.

Fareed Zakaria: (11:38)

So I think a lot of the answer is that Anthony, but finally, I would say this and you know this better than I do and this is what Trump gets, you got to give this people dignity. You got to give them a sense of respect. When we talk about essential workers, when we talk about ... that's the right kind of language for us to use, not just about essential workers, but about farmers, about people in construction, about people who are working in mines. I mean, I think that even talking about this transition, it's not the right way to think about it. It's you first begin by honoring these people.

Fareed Zakaria: (12:12)

And then you say, what we are trying to do is to make sure that your children can have the same kind of dignity and work and study. And we are therefore going to find great jobs in the future for those people, but you, we honor, we respect and we want to help make sure that your family has the same kind of life that you've been able to have. Something like that. But I think we shouldn't minimize the dignity part because a lot of what the right is better at doing than the left is the dignity, even though they don't spend any money on these people.

Anthony Scaramucci: (12:43)

Well, I would say that it's the right coincidence with President Trump. I think it was prior to President Trump, probably not as much. In fact-

Fareed Zakaria: (12:51)

Correct.

Anthony Scaramucci: (12:52)

... what I once wrote is that there was a vacuum of advocacy for these people on both sides in the establishment for three decades, which gave Mr. Trump the opportunity to exploit that in 2016. You bring up in your book, which I found fascinating, you more or less say that the way the world is now organized, it seems like we're having a seizure or an economic crisis, or now it being a healthcare crisis once every 10 or so years. And if you think about it, the 1998 crisis, which led to the Fed intervention, long-term capital management crisis, the 2008 crisis, the COVID-19 crisis, we could go back. And I'm just wondering why you think that is? Why do you feel like the way we've set up the mechanisms and architecture of globalization is causing these once or so, once a decade or so seizures?

Fareed Zakaria: (13:45)

Yeah, it's a great question because I puzzled about it myself. And I think that fundamentally, if you look at the system we've created and obviously nobody sat down and created it, but that we have allowed to build up. The system is very fast, very open and very unstable. It's very fast. It moves at lightning speed, accelerated by information technology. It's very open. Every country can participate and that is multiplied by the information revolution.

Fareed Zakaria: (14:14)

But we've never wanted to put in safeguards, guardrails, seat belts. We've never wanted to buy insurance because you don't want to slow it down. But the danger of a system like that is that it can careen out of control. So I mean, at some level you can think of 911 as the kind of reckless expansion of Western liberalism and democracy everywhere in the world without much attention to the parts of the world that we're really showing a backlash against it. And with a minority of people in the Middle East, but we saw pretty violent backlash to that idea.

Fareed Zakaria: (14:49)

If you think about the global financial crisis, right? I mean, ever since we have massively deregulated the financial space, is basically since the 1990s or late '80s, you've seen a lot of these crises. I mean, the SNL crisis, the Latin American debt crisis, the Tequila crisis, the Asian crisis, the Russian default, the global financial crisis. And if you look between 1938, roughly when FDR regulates to 1985, not a lot of crises, but a much slower system. So I'm not saying we know what the balance is, but clearly it is out of control right now, because we are seeing, it's not just the pandemic. We're seeing forest fires in California that, I mean, we've burned five million acres of land. That's the entire state of Massachusetts up in flames because between global warming and the way we have actually incentivized people to live at the edges of forests, it's an invitation from one of these accidents to careen out of control.

Fareed Zakaria: (15:52)

Factory farming, the way we do, it's an invitation for another pandemic. So I want us to think more about resilience and security, maybe sacrifice a little bit of dynamism because the thing you don't know, Anthony, is one of these could be the last, or at least could be so severe that it becomes ... just imagine if we had been able to sacrifice some dynamism and not had the global financial crisis. The world probably spent $20 trillion recovering from that. Imagine if we could have bought a little insurance and been a little careful about human development, so we don't have these constant contacts between animals like bats and human beings. We're going to spend, I don't know, 30, $40 trillion on this pandemic by the time we're done with it. It would so much be worth a few billion dollars, a few tens of billions of dollars in prevention rather than the cure.

Anthony Scaramucci: (16:53)

Very well said, and hopefully we'll get there. Your lesson 10. I mean, I loved all of the lessons frankly, but the lesson 10, I found fascinating because you really do understand the Post-World War II architecture. You mentioned a little known fact by most Americans that FDR really started the process in '43 into '44 with the notion of the Post-World War II architecture starting, even though the outcome of that war was uncertain. He knew that and he was a Wilsonian in many ways because he was the undersecretary of the Navy for Rob Woodrow Wilson.

Anthony Scaramucci: (17:31)

And when I was reading that and reflecting upon it, I was actually listening to it on audio tape. And then I went back and looked at it in the book, when I was reflecting upon it, it's 75 years out. It's been by and large successful. We've had peace and prosperity as a result of the Post-World War II alliances and the architecture. But I'm wondering now, because a lifetime has gone by, 75 to 80 years, is it time for a reset? And if it is time for a reset, Fareed, what would that reset in your mind look like? What would it need to look like to continue peace and prosperity and the lifting of the rest of the world into middle-class living standards?

Fareed Zakaria: (18:10)

God, you're asking all the big questions. I mean, I think that's in a way the central international question and you're right. There's no question. I mean, FDR was a total visionary. And you really have to imagine in that situation isolationist America, 43, as you say, one and a half years after Port Harbor and he's already thinking that we are going to create a new world order. We're going to create a new system. We're going to create an architecture that gives the great powers and incentive to be in there.

Fareed Zakaria: (18:38)

He was at Versailles visiting as under assistant secretary of the Navy. And he said, "Wilson's ideals," roughly speaking what he said was, "Wilson's ideals were the right ones, but the guy doesn't understand, it's not going to work if you just say these are the laws and these are the rules. You got to give the major countries an incentive to be there." That's why we ended up with the security council. That's why we ended up with the great powers Veto which invests the strongest countries in the world, in the system.

Fareed Zakaria: (19:09)

So that is in some ways at the core of my answer to your question, we will not be able to sustain this system if the most powerful countries in the world today, not in 1945 are not invested in. If you think about the architecture now, I mean, the five countries that dominate are the five countries that won the war in World War II. Was actually four countries, we pretend that France won the war when it really didn't.

Anthony Scaramucci: (19:38)

Oh, not to interpret but I will. It's sort of like the Dow or the S&P, Fareed. We recirculate, again to show you that the Dow 30 in 1945 are not the same as the Dow 30 today or even 10 years ago for that matter. I think it's a very interesting point.

Fareed Zakaria: (19:54)

No, exactly. Now another analogy though, which is a little less hopeful is the American constitution. I happen to be, as an immigrant, a huge fan of the American constitution. I think it got more things right than any constitution has ever gotten right. But it is an 18th Century document. Parts of it are badly worded. I mean, the second amendment, frankly, is just a grammatical mess. Nobody even knows what it means when you talk about a well-regulated militia. So there are parts of it that clearly need updating, but it's very hard to do.

Fareed Zakaria: (20:28)

So the real challenge here is going to be to do a kind of software update, a soft update. You're not going to be able to say, we're going to bring the system down and we're going to start from ground zero. But we have to find a way to incentivize the most powerful countries in the world that could otherwise be the spoilers to in some way be part of it. It doesn't mean that they're all going to be beautiful, liberal democracies and the world is going to be at peace. No.

Fareed Zakaria: (20:54)

China is going to be a competitor. We're going to have to play hardball with it. We're going to have to find ways to out-compete it. We're going to have to find ways to push back against it on many issues, but we both have a very strong overriding interest that there'd be an open system, a rule-based system in which mostly things are resolved by dialogue and not by force in which everyone can trade with everyone. So if we can come up with a set of rules and try to incentivize people, and what does that mean? It means we blew it in the Obama Administration on something called the Asian Development Bank.

Fareed Zakaria: (21:31)

The Chinese came to us and said, we want more influence in the Asian Development Bank, which is basically a public financing mechanism in Asia, and we'll put in a lot more capital. Obama Administration said, no. The Brits actually advised us to exceed to the Chinese demand. And we're like, no, we like the fact that we dominate the Asian Development Bank. So the Chinese say, okay, we're going to go off and take our marbles, and we'll start our own thing called the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank, which I think got five times as much paid up capital as the ADB. So they went out and freelanced, created their own alternate system. It's working better than the ... and the Asian Development Bank is dying. We've got to think that example through a hundredfold.

Anthony Scaramucci: (22:14)

A hundred percent. They did the same thing with the Export Import Bank for China versus our EXIM Bank in the United States.

Fareed Zakaria: (22:20)

Exactly.

Anthony Scaramucci: (22:20)

Fareed, you wrote an amazing book. I have to turn it over to John Darsie because we have huge audience participation and we've got tons of questions coming in. And so I'm not that promotional, right? Fareed, so look, I'm like using the book as a windshield wiper, see that, but it's an amazing book. I encourage everybody to read it and wish you great success with the book. And I'm looking forward to your future writing on this topic, because I think you're right on point in where the world needs to go. So congratulations Fareed, I'm going to turn it over to John and all that blonde hair, Fareed. Look at all that American blonde hair.

John Darsie: (22:58)

All right, I'll-

Fareed Zakaria: (22:59)

Thank you Anthony.

John Darsie: (23:01)

It's my pleasure to take the baton. So Fareed, I want to elaborate more on what you talked about in terms of humans encroaching on animal habitat. So it was a great book that we've talked about before on previous SALT Talks called Spillover written in 2012, that more or less predicted elements of this pandemic. And you write as one of your lessons in the book about how the pandemic and likely future pandemics is sort of nature's revenge for overpopulation, human environmental encroachments. And you also worry about the implications of a meat-based diet. Could you elaborate on all the different implications of more people around the world moving into consuming meat and the implications that has for our planet?

Fareed Zakaria: (23:42)

Sure. So first thing to remember is the more meat we're eating, the more unhealthy we get. Small amounts of meat are perfectly fine, but larger and larger amounts of meat correlate with all kinds of terrible dietary issues. One of the reasons, by the way, that we don't talk about why America has been hit so badly by COVID is we're all obese. The United States has a massive obesity problem. And as a result, and that is essentially a disease multiplier. But the problem with a meat-based diet is fundamentally, it is terrible for the environment in terms of global warming. The amount of farmland you need to produce the amount of calories we consume from meat is massive. I can't remember the exact numbers, but it's something like 40 or 50% of the farmland for 15% of the calories.

Fareed Zakaria: (24:32)

So secondly, there's a huge amount of methane that is released into the air. And thirdly factory farms, which is by the way, how 99% of meat is produced. So if you think you're having organic meat in Europe solving the problem, you're not. You're 1%, 99% of meat is produced through factory farms. Your hoarding animals together in incredibly unsanitary conditions, and you've chosen animals that are genetically selected to be similar, because that's the whole point of factories, you're producing exactly the same product.

Fareed Zakaria: (25:06)

And that means that these animals have no defenses against viruses. So the virus just keeps hopping from animal to animal, getting more and more powerful. You've injected the animals with antibiotics. So the viruses are now becoming antibiotic resistant and this is a Petri dish for a pandemic. And my great fear is that COVID-19 is the dress rehearsal for what is going to be a more Virial inversion of a respiratory virus born out of this factory farming.

Fareed Zakaria: (25:41)

So you've got global warming issues. You've got environmental issues and you've got pandemic issues. And most importantly, your personal health will be substantially alleviated by reductions of animal protein. Now, to be clear, I'm not a vegan, I'm just careful. I think it's very important to ... my sort of approach in life is our Aristotelian, everything in moderation. But I'm very careful about how much meat I eat, because it's bad for me. It's bad for the country. It's bad for the planet.

John Darsie: (26:16)

So we've seen certain countries and your point about this current pandemic being a wake up call from a potentially more deli future pandemic is well taken. And we've seen certain countries and certain cities be much more resilient and effective in fighting the spread and the morbidity of COVID-19. What cities and countries have stood out, and what can we learn from their success in preventing the spread and in treating the virus?

Fareed Zakaria: (26:41)

Sure. It's a really good question because we really have a wide variation. It's exactly what a social scientist would want, and almost that kind of natural experiment. So probably the gold medal goes to Taiwan. Taiwan is about 24 million people. It's right next to China. It gets huge amounts of traffic from China, tourists, business travel, millions and millions of people. And despite all that, Taiwan has had, I believe, seven COVID deaths. So to give you a sense, New York state, which has 19 million people, 5 million fewer than Taiwan has had 35,000 COVID deaths, roughly 34,000, I think.

Fareed Zakaria: (27:22)

But Taiwan's death rate is 1:2000 that of the United States. So you ask what they've done right? First thing they did was they acted early. They decided having gone through SARS and MERS, they realized, you know what? Better to take no chances and they got smart early on. Secondly, they were aggressive. They put in place some travel bans. They put in place some immediately, if you came off the plane, you were coming from China, they took your temperature. They made you do certain kinds of checks. They kept your information. And then they started banning a certain amount of the travel.

Fareed Zakaria: (27:58)

Most importantly, they immediately ramped up mass testing and tracing and isolation. We don't talk about that because it's the inconvenient part. You have to quarantine the people who are potentially infected. The whole thesis behind the Taiwan strategy is, a lockdown is a bad idea because it shuts down the economy. A lockdown is a sign you've already failed. So what you're trying to do is say, this doesn't just spread randomly through the public, it spreads in clusters. So the minute you find one person who has it, you are trying to capture that cluster of potential infectees. Isolate them, separate them from the population, and they did this in Taiwan.

Fareed Zakaria: (28:43)

In total, they separated 250,000 people for 14 days at a time obviously, not all at the same time. But that's 1% of the population of Taiwan. So they were able to keep 99% of the country, the population fully operational by just selectively and strategically, and immediately pulling out those people who might be infected. So it's only aggressive and intelligent. We were late, passive and stupid.

John Darsie: (29:14)

So Mark Meadows, the White House Chief of Staff told your colleague Jake Tapper this weekend that we basically just need to give up on trying to contain the virus. It's not going to happen in America. People value their freedom of movement and the right to wear a mask or not wear a mask too much. We need to focus on therapeutics and getting a vaccine. Is our inability to fight the virus a lack of political will to put these systems in place to fight it, or is there a lack of testing capability that's more of a product of lack of scientific development and manufacturing development? Can we do this if we decide that we have the political will to contain it, the spread, not just the death rate?

Fareed Zakaria: (29:57)

We absolutely could do it. We could still do it. First of all, to explain why we don't have a mass testing and tracing system in place, it is purely a political decision. The testing piece is trivial. Do you know why we don't have real good testing in America? Because the federal government has not made a distinction between tests that are returned within 24 hours, within 48 hours, within three days. But tests that with the results you get three days later is essentially worthless. You're trying to figure out when people are infectious and separate them. So you're infectious for about three or four days, maximum, during the course of this disease. If you get the tests back three days later, you've already passed the point where you're infectious. So at that point, there's really no point in isolating somebody.

Fareed Zakaria: (30:48)

So the whole point of isolating is once you find out that somebody is positive, you put them in a place where they can't infect anyone else. So if the federal government will not make a distinction in reimbursing, why would a private company, you guy, most of your viewers are business people. Why would a private company be stupid enough to incur heavier costs, to turn around the test in 24 hours as an act of public virtue? They're not going to do that.

Fareed Zakaria: (31:15)

The feds have a very simple solution, which is you reimburse double for a test that you get back in 24 hours, normal rates for 48 hours, and maybe 10% for anything that comes back afterwards. You would see the testing regime change in a minute. I mean, these companies could do it easily, but while they have 95% margins, why are they going to do it now?

Fareed Zakaria: (31:38)

The tracing piece, yeah, there's a little bit of a challenge there. But other Western countries have been able to do it. Germany has a very good tracing system in place. Some of the Northern European countries have a very good system in place. No, we are just being defeatist. And the Trump Administration has decided that their election strategy is to say, look, this was not something one could handle, so any change to the system would imply that they made a mistake and Trump hates to admit he's made a mistake. The real truth is what we should be doing is saying we failed, happens in life, whatever, that's history. We can learn from the failure and we can still set it right.

John Darsie: (32:18)

So I want to shift gears a little bit to a couple other themes that you've written about a lot in the past and you talk about in this book as well, which is the growing digitization of the world and our migration that's been accelerated by COVID to life on the internet, remote work, the rise of robots and robotics, artificial intelligence. Long-term, what do you think the implications of the pandemic are to the speed of the development of those technologies? And what do you think those technologies look like in our society in say 10 to 15 years from now?

Fareed Zakaria: (32:52)

Yeah, it's a great question, and it's a big question. The way I think about it is what the pandemic did was it massively accelerated an ongoing trend, which is, we were clearly transitioning to a greater and greater digital life, but it's massively accelerated it. Look at telehealth. It was very hard to get people to go to their doctors. People like to go and physically meet with the doctor. The doctor like to meet with you because the doctor got paid more when they met with you.

Fareed Zakaria: (33:21)

Suddenly COVID has eliminated all those human obstacles, and you're going to have one billion tele visits or health visits by the end of 2020. Most people had predicted that would take about 10 years to happen. So you're massively accelerating it. Now in doing that, my fear, there are a lot of hopeful things about that because it massively increases productivity. It massively increases the scale at which you can operate.

Fareed Zakaria: (33:48)

Think about education. One of the things that will come out of this is we're doing it badly right now, but online education will be totally transformed because by having this huge, massive stress test to the system, we're going to figure out what pieces work, what pieces don't work so well. I've got a son in college who already, they're all piecing it together. They're realizing, if it's a lecture, Zoom works fine. In fact, you don't even need to Zoom, you can listen to the lecture as a podcast while you're doing something else. You're biking or you're running or you're walking.

Fareed Zakaria: (34:24)

But for a discussion section, Zoom is not that great because you don't ... so you're finding some areas where the technology is actually great. You're finding in some areas where it needs a lot of work, you need to supplement it. I find that with dealing with my teams for the show. Building social capital on Zoom is very hard, spending it is easy. If you already have good relations with people, you already have a good working environment, you can execute. But what about the new person? What about the new process? What about the new ... what about the little stuff that you haven't thought about?

Fareed Zakaria: (34:57)

So all that is the challenge, the dark side, and I end with this is it's happening really fast. So if you think about globalization, one of the reasons we're in the situation we are with the anti-globalization mood is that China and perhaps to a lesser extent India, were just such large shocks to the system. Before that, when we had expanded globalization, what did it mean? Japan came online, 50 million people, South Korea came online, 30 million people. Singapore, Taiwan, 10, 15 million people in total. And then you get China, one billion people. Then you get India at the time, 800 million people. And so the scale was just so much larger than anything we had dealt with before that it did cause an impact both economically and politically. I worry that the speed with which we are now going to make this digital transition is going to just be devastating.

Fareed Zakaria: (35:57)

So let's say it transforms the restaurant industry, which I think it will. And you will have a much greater degree of online web based delivery systems at a smaller number of high-end restaurants, where you go for the real experience of a kind of really cool bars where you're going for the atmosphere. So there will be some kind of sort. Normally, maybe it would have taken 20 years for this to happen. If it happens in the next two years, what happens to all those people who were waiters and busboys and the bellhop at hotels? So change is good, but when change accelerates that fast and almost unnaturally, are we ready for it? And that's one of the reasons that I come back to the importance of government as a stabilizing force to try to help us get through what is in a crazily accelerated transition to digital.

John Darsie: (36:53)

So what are those solutions? That's a great segue to a couple of audience questions. There was one that was focused on India. India is obviously undergoing massive economic development and digital development. You're seeing the growth of the technology industry is very fast right now in a place like India. It's the same type of phenomenon we've seen across the world in China and the United States. What type of government policies do we need?

John Darsie: (37:16)

Obviously, you talked about technology providing a more level playing field in terms of access to telemedicine and health care, better access to at least the bare minimum quality of education in the form of lectures and things like that. What type of government policy specifically would you like to see in the United States or elsewhere to make sure that people on the bottom rungs of the ladder at least have the means to live not an impoverished life?

Fareed Zakaria: (37:42)

It's a great question. Look, it's quite different I would say honestly. A place like India, you're still facing the fundamental challenge that about 600 million people in India still live on less than $2 a day. And one of the reasons is that the Indian economy remains very closed, very regulated, very socialistic. And so in India, the answer is open up, open up, open up, you need growth. You cannot get those people out of poverty without growth.

Fareed Zakaria: (38:13)

China is the perfect example of that. You have to focus first and foremost on growth. And you have to focus on employment friendly industries. The places that employ large numbers of people. And for India, that means you've got to do everything. You've got to do factories. You got to do retail. You got to do large-scale agro. You've got to find ways to open up the labor markets, bring in foreign investment. It's all the traditional mechanisms that have allowed countries to grow by embracing markets, by embracing development, by embracing trade.

Fareed Zakaria: (38:47)

For India, you've got to a long way to go before you start having the problems of too much growth, too much development. So in India, I would say, really think of just opening up, and all the technology is good because it leapfrogs all kinds of ruin-ness and dysfunctional technology. So there's a 4G system in India that's been put in place, amazing for increasing productivity for farmers, for laborers, for anybody.

Fareed Zakaria: (39:16)

The US and the Western world faces a different problem, which is the traditional working class of these countries. The non-educated working class, by which I mean people without college degrees or even much technical training, and it's important to make that distinction. Workers with technical training, for example, electricians, plumbers, are doing fine, and they can adapt very well to the new economy. They can adapt to working on wind turbines or solar panels or whatever it is.

Fareed Zakaria: (39:46)

But it is a more traditional working class, the less skilled, what would have been called semi-skilled jobs that is much harder hit. For these people I think you just, as I was saying to Anthony, you got to spend more money. I mean, we've been very ... Obama gave a great speech once or some remarks where he talked about the signing of, I think it was the South Korean free trade deal. And he said, "We all know that the trade is good and more trade is good. It opens up, it grows the buy, but we always say, we understand that it dislocates some people and we should spend money on them, and then we never spend any money on them and then that resentment grows."

Fareed Zakaria: (40:25)

It was prophetic in a way, because that has been our principle problem. We know that there is going to be a period of dislocation, and there are going to be parts of the country that are dislocated. And in other words, this is not spread evenly throughout the country that you get all the benefits evenly and all the costs to people. The benefits are spread roughly evenly. The costs are highly concentrated in particular towns, in Pennsylvania, in Wisconsin, in Michigan, in Ohio. And you have to have a strategy that addresses that. And frankly, that helps these people.

Fareed Zakaria: (41:00)

Some of it is just cash. Some of it is retraining. Some of it is figuring out new apprenticeship programs. Well, we need something on the scale of the GI bill. The great thing about the GI bill was it was a very American and ingenious solution, which was, the federal government will pay, but it will not administer anything. The private sector, as it were, colleges, both state, religiously oriented, private would provide the service. So the deal was, if you'd been a GI and you presented your proof of it, you could go to any college for any degree of any kind and the federal government would pay.

Fareed Zakaria: (41:40)

I think that the federal government does very well writing checks. They know how to do that very well, but administrating stuff they're less good at. So try and find a similar, where maybe the private sector identifies the needs. Here's what we have. We need welders, we need whatever. The federal government provides the resources and the community colleges maybe, or state colleges do the training, some kind of triangle like that. And what stops you just to be clear is, it's not that we couldn't come up with the genius programs, What stops us is the resources. You'd have to spend a lot of money. I'm talking about tens of billions of dollars on this.

John Darsie: (42:19)

So you talk about, we're going to leave with one last question. You talk a lot about these trends, and in a lot of ways, the book is very depressing or concerning because you see so many things happening that are moving us in the wrong direction as a world. But let's imagine five, 10 years in the future. Let's say we have a change in administration in the United States. Vice president Biden wins the election as the poll seemed to indicate that he will.

John Darsie: (42:44)

Do you think this rise in nationalism and this attack on globalism is a permanent phenomenon that's going to continue, or if not permanent, at least a cyclical phenomenon that's going to continue for 10 to 20 years, and it's really going to erode our ability to fight things like climate change and global poverty? Or do you think that we can do a course correction right now at this moment in time and move back into a direction that is more stable in terms of global peace, global prosperity?

Fareed Zakaria: (43:13)

Look, I hope we can. I'll tell you why.

John Darsie: (43:15)

No problem.

Fareed Zakaria: (43:16)

You talk to any venture capitalists in Silicon Valley and you ask them, what do you want? What's the first kind of person you want? The first kind of person you want is like Elon Musk who succeeded at two or three different things. But let's say you can't get Elon Musk. You want somebody who failed, but who learned from that failure. I think that the key here is do we have the capacity to learn? We're going through some very tough stuff, but you only change when you fail. As a company, as an individual, as a country, it's easy to do nothing when times are good. But it's when times are hard, when you face dislocation already, when you're looking at failure, you now have the chance and the opportunity to change.

Fareed Zakaria: (44:03)

So I think we should view this and not sugarcoat it and say, look, we failed in our response to this pandemic. And by the way, a lot of countries failed, what can we learn? How do we do it better? We have the opportunity to embrace a different future because stuff is already so dislocated. People are open to the idea that we need to figure this out better. I look at the European Union, they started off their response to the pandemic was very much like ours, close, narrow, selfish, turn inward. The Italian started blaming the Germans. The Germans started blaming the Italians. And then there was a kind of come to Jesus moment where they thought to themselves, wait a minute, what are we doing here?

Fareed Zakaria: (44:43)

We're screwing up the entire European experiment. And instead what they did was they reversed course. And the Germans for the first time along with the French, essentially agreed to those, what was always called Euro bonds, basically to guarantee the debt of the poorer countries so that they could all get out of this. And doing that, they're also creating stronger bonds among the Europeans than they had before. So I predict that the European Union will come out of this crisis actually stronger than it was going into the crisis.

Fareed Zakaria: (45:16)

So in a way, why can't the world do the same? Because the truth is we've all been drawn inward, but we are all coming to realize you can only solve this together. It's a global pandemic by definition. We're not safe unless everybody is safe. We're not going to be safe either with climate change if we don't do it together. We're not going to be safe with space wars if we don't do it together. There're so many of these challenges that really require not global government, which that's a kind of bugaboo that people do to scare, but global governance. Agreements made by sovereign governments to cooperate.

Fareed Zakaria: (45:52)

And by the way, that's how human beings have survived. I mean, we've survived because of a strange mix of competition and cooperation, but the evolutionary biologists will tell you, the dominant trait was that we know how to cooperate. We know how to therefore operate at scale, and we know how to get to win wins. And what we need to do now for the world is get to a win-win.

John Darsie: (46:14)

All right. Well, that's a perfect place to leave it, an optimistic message. Thank you Fareed so much for joining us. It's an absolute pleasure. We would encourage everyone to go out and read your book. It's sitting right behind Fareed right now. Thanks again, everybody for joining us and thanks again Fareed for taking the time to sit down with us on SALT Talks.

Fareed Zakaria: (46:31)

A real pleasure. Take care, guys.