“[When starting my company,] I figured you wanted to own equity, be a partner. You wanted to wake up in the morning and it be your business… To have that culture where people own equity is critical.”

Eric Gleacher is a man with a compelling story. He has always been determined to excel in all that he attempts and has never failed to exceed the very high expectations he sets for himself. His autobiography is the story of a tournament-winning amateur golfer; an officer in the Marine Corps; an investment banker who became one of the half-dozen who dominated the M&A and takeover business that changed Wall Street and American business in the latter part of the last century; and a man who had the courage to leave a position as a senior partner at a famous and immensely successful investment bank to establish his own firm. It's as stirring and interesting as when we lived it. You won't want to stop reading until the last page.

Eric discusses his winding and eclectic career with time in amateur golf, the Marines, Lehman Brothers and Morgan Stanley where he transformed the M&A industry, before starting his own firm. He describes the formative impact amateur golf played in his life and how lessons learned helped in business. When starting his own firm Gleacher & Company, he explains the importance of offering equity to employees in developing a thriving culture.

LISTEN AND SUBSCRIBE

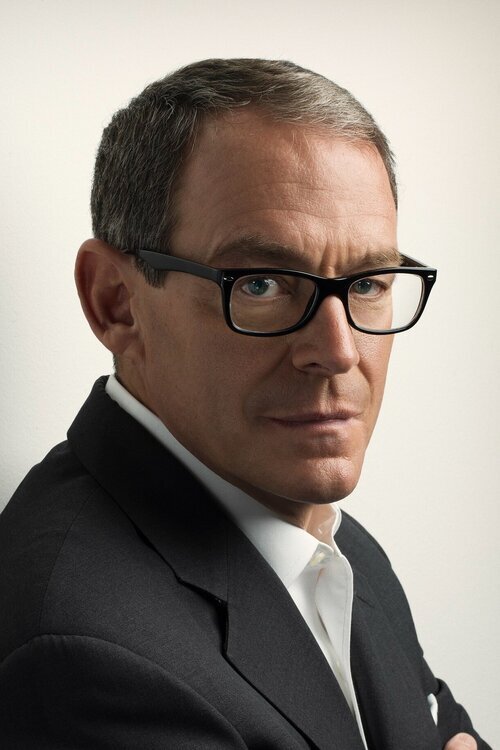

MODERATOR

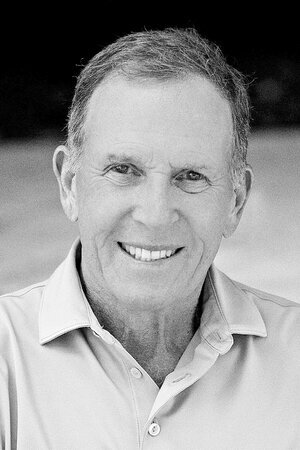

SPEAKER

Eric Gleacher

Author

Risk. Reward. Repeat.

Anthony Scaramucci

Founder & Managing Partner

SkyBridge

TIMESTAMPS

0:00 - Intro

3:54 - Supporting women on Wall Street

6:00 - Winding career path and taking smart risks

13:50 - Time at Lehman Brothers and Morgan Stanley

19:16 - Revlon M&A

24:20 - Impact and lessons from golf

35:22 - Building a culture at Gleacher & Company

38:21 - Writing his book

42:29 - Favorite golf courses

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

John Darsie: (00:06)

Hello everyone, and welcome back to SALT Talks. My name is John Darsie. I'm the Managing Director of SALT, which is a global thought leadership forum and networking platform at the intersection of finance, technology, and public policy. SALT Talks are a digital interview series with leading investors, creators, and thinkers. And our goal on these talks is the same as our goal at our SALT conferences, which is to provide a window into the mind of subject matter experts, as well as provide a platform for what we think are big ideas that are shaping the future.

John Darsie: (00:39)

We're very excited today to welcome Eric Gleacher to SALT Talks. And Eric is a man with a extremely compelling story. He's always been determined to excel in all the attempts and has never failed to exceed the very high expectations that he sets for himself.

John Darsie: (00:55)

His autobiography, which we're going to talk about today, is the story of a tournament winning amateur golfer, an officer in the Marine Corps, an investment banker who became one of the half dozen who dominated the M&A and takeover business that changed Wall Street and American business in the latter part of the last century, and a man who had the courage to leave a position as a senior partner at a famous and immensely successful investment bank to establish his own firm that he ran for almost 25 years.

John Darsie: (01:24)

Hosting today's talk is Anthony Scaramucci, who is the Founder and Managing Partner of SkyBridge Capital, a global alternative investment firm. Anthony is also the chairman of SALT. Anthony is successful in business, but he can't golf a link, but we won't hold that against him, Eric. But I'll turn it over to Anthony for the interview.

Anthony Scaramucci: (01:40)

Why don't you tell Eric I got fired from the White House while you're at it? You might as well [crosstalk 00:01:44].

John Darsie: (01:43)

There's only one slight-

Anthony Scaramucci: (01:43)

It's not like he doesn't know that, but go ahead, John.

John Darsie: (01:47)

There's only one slight per introduction, it's either the fact that you're terrible at golf or the fact you got fired from the White House.

Anthony Scaramucci: (01:53)

That could be a compliment to my buddies that don't play golf. You don't know that.

Eric Gleacher: (01:56)

It's a badge of honor.

Anthony Scaramucci: (01:58)

Well, listen, Eric, first of all, it is a pleasure to do this with you. And you wrote a legendary book. I read a lot, John will tell you that. I've tried to read 60 books a year. This book came to me from my lawyer, Ed Herlihy, who worked on our M&A deal for SkyBridge, another phenomenal world class person. But, I mean, the book is just chock full of great stories and lessons and principles.

Anthony Scaramucci: (02:29)

And so, it's called Risk. Reward. Repeat.: How I Succeeded and You Can Too. John always prints out a script for me for these things, because he's keen to at least give me a few questions that he thinks are thoughtful, Eric, because he gets all the praise for asking the thoughtful questions. But I read your book, and one of the things that came out of the book for me is you're a cutting edge thinker. You're somebody that saw the future in our industry and a number of different trends. But I think you've done an amazing amount for a lot of different types of people.

Anthony Scaramucci: (03:08)

There are women in our industry that say that you were the great equalizer, that you brought them to the table, and that many places there were glass ceilings for them but you broke... You didn't write that in your book, by the way, you wouldn't give yourself that self praise. But this is actually coming from friends of mine that worked for you, that you mentored, and that you trained, but you also pushed them through the glass ceiling. I want to start there, sir, and then I'm going to go back to other things.

Anthony Scaramucci: (03:38)

What was it about these women that you saw? What was it about these women that were drawn to you as they were breaking into what you and I both know, at those times on Wall Street it was a little bit different culture than it is even today?

Eric Gleacher: (03:53)

What it was about these women is that they were very smart. They were tireless, and they wanted it, but they didn't know how to get there. And to me that was a challenge because I...

Eric Gleacher: (04:13)

One thing I learned at the beginning of my life experience, and what I mean by that was, when I was done with college and I chose to enlist in the Marine Corps that's when I really started learning things. And one of the things I learned very quickly is the power of delegating. And so with these women what I did was I put them in situations that were really ahead of where they were in terms of their development in the business. And, of course, they excelled. And that led to other things and other successes.

Eric Gleacher: (04:54)

And there's a lot of them I could pick out. For example, there's one who was a Chinese studies major at Radcliffe or Wellesley. And she was from the West Coast up in Seattle. And she spent her junior year in China. And she knew nothing about business, and yet she picked it up so fast that within a year she was the top analyst that I had in the M&A department at Morgan Stanley. So that just impressed me. And I enjoyed it. There weren't that many women there, but to give a few of them an opportunity to excel and hear feedback like you got, that's a home run as far as I'm concerned.

Anthony Scaramucci: (05:45)

Look, it's a tribute to you, because it was a different culture and a different time, sir. So tell us about the journey though. Tell us about the journey from high school into the Marine Corps out to Wall Street. Why was that your career arc?

Eric Gleacher: (06:00)

Well, I had an unusual journey because I was born in 1940. My father, obviously, I met him when I was an infant, but before you knew it he was off in the war. He was gone. And he was a CB, which are the Navy construction battalions. And he was working in the Marianas out in the Pacific building the airfields for the bombers to go to Tokyo and back without having to refuel.

Eric Gleacher: (06:29)

And when the war ended he didn't come home for a couple of years. He got jobs outside the country. And the reason I tell you that is because when he did come home I was seven years old, so I was just getting to know him. And he never once would talk to me about what went on. So, it was a very unusual experience for a young kid. But then we found that we started playing golf together when I was 12, and lucky enough I could get up and I could hit the ball and I kind of had an aptitude for it. And we became very close. And so I ended up with a real happy ending in my childhood.

Eric Gleacher: (07:18)

But my dad was a construction engineer. That's what he was doing in the Navy, and that's what he did for the rest of his career. And we moved around. I went to 10 different schools. There'd be a job, and it would end, and he'd find another one, and it didn't matter where it is, and we went there. So when I got to college really I didn't know a lot, it opened my eyes about people and how other people live and things I didn't know. And I didn't know anything about business.

Eric Gleacher: (07:54)

And when I graduated from college back in those days you either had to keep going to school or you had to do military service, and so I decided to do that, and I decided to go into Marine Corps because it seemed to me it would be the most challenging thing I could do and that's what I wanted to do. And that was a great decision, because right away there were all kinds of challenges, and the book goes through them.

Eric Gleacher: (08:23)

And to successfully navigate my way through that was the first thing I ever did in my life, except win a golf tournament, that was really a success, and that's really got me going. I acquired self confidence and went on from there. And I learned a tremendous amount being in the Marine Corps.

Eric Gleacher: (08:46)

You talk about women, I was a rifle platoon commander in the infantry, so I had 45 men. Most of them did not have a high school education, but I found out that plenty of them were smart as hell. And that's where I learned to delegate and to give people an opportunity. And you'd be amazed in terms of what they can do. And so I enjoyed it a lot. I was in for three and a half years and ready to go to school when I get out.

Eric Gleacher: (09:23)

I decided to go to business school because I didn't know anything about business. The one thing I wanted to do, which was a function of what I went through growing up, was I wanted to make money because my family never had any extra money. And so I decided to go to business school because I didn't know anything about business, and fortunately, I got interested in finance at the University of Chicago, which is a great financially oriented school. And I found my way to Lehman Brothers. So that's-

Anthony Scaramucci: (09:56)

Well-

Eric Gleacher: (09:56)

... how it evolved.

Anthony Scaramucci: (09:57)

... I want to get to Lehman in a second, but you place a particular emphasis in the book on taking smart risks. So I want you to analyze that decision. You're coming out of business school, you're going to work on Wall Street, you choose Lehman. Take us through that thought process.

Eric Gleacher: (10:13)

Well, the first smart risk I took was since I was going to go into the military I was going to do something that was real, that had some significance. And back in those days there were lots of six months reserver's programs, you could go into Air Force reserve and so forth, and I didn't want to do that, so I said, okay, I'm going to go into Marine Corps and really see what it's all about. And I learned so much. It affected my life so much, and that wouldn't have happened if I wasn't willing to take that risk and sign up for three and a half years instead of some six month reserver's program. And it started there.

Eric Gleacher: (10:57)

And I've said it in the book and I really believe it to the core of my being, is that the world belongs to the aggressive, and you can't just sit back. I have trouble politically with what's going on now because the politicians want to give people things, and most people I know don't want to be given things, they want to earn things, they want to have a job, they want to have self respect, they want to have a home, they want to have a kid, they want to send the kid to school.

Eric Gleacher: (11:31)

And so those values, all those things, I think, I accumulated by how I started. And like I said, deciding to do it right in terms of going into military rather than take the easy way out. And by the way, I can understand why it all changed after Vietnam and why the military establishment wanted to have a volunteer force. But boy, we left a lot on the table doing that. I think that we'd have a very different situation in Chicago, just to pick an example, with what's going on here how if you had compulsory military service at least for men when they turned 18. So, the way I look at it I was lucky to be able to go through it.

Anthony Scaramucci: (12:26)

Well, let me take it one step further though, the compulsory service, you would have taken a lot of kids off the street, they would have gotten trained, they would have learned some discipline, but they would also have been in esprit de corps and some civic virtue to all of that that would have probably binded the country more closely together. Is that fair to say?

Eric Gleacher: (12:44)

Not only that, it's absolutely fair, but a lot of them would acquire an occupation. I talked to a young guy this week who's going into Marine Corps, he's going to train as an aircraft mechanic, and when he gets out he's going to have that trade. And that was true way back when I was in it. There were opportunities like that. And you're right, if you have an 18 year old kid who all of a sudden he's part of a group, and there is esprit de corps and so forth, and he's bright and motivated, he can take advantage of things like that, whereas now that opportunity does not exist.

Anthony Scaramucci: (13:29)

So let, and you and I agree on that, let's shift gears for second, let's talk about Lehman. [inaudible 00:13:35] book many, many years ago, there was a battle there between Lew Glucksman and Pete Peterson. And there was a lot of very smart people in that room, yourself, Steve Schwarzman, etc. Tell us about Lehman Brothers while you were there.

Eric Gleacher: (13:51)

Lehman Brothers was full of really talented people, but in those days it lacked a cultural backbone. And the people, the senior people at Lehman, the partners, were basically competing with each other rather than pulling together. And so you had various fiefdoms and the firm had its ups and downs. It was a place that did well, it went on for many, many years, but everybody knows what the ending was.

Eric Gleacher: (14:33)

And, to some degree, the end was a function of the beginning. But there was just tremendous infighting at Lehman, you had Peterson and people that were with him and Glucksman and Jim Glanville and others that were another group. And it was good for somebody like me because you could move at your own speed there. It wasn't stratified. When I got there I was the 15th guy in the, what they call the industrial department, which would have been the corporate finance department.

Eric Gleacher: (15:10)

There was no M&A. M&A really didn't exist then. And you could move at your own speed. There wasn't a lot of management. When I got there I was 27 years old, and I had a wife and a kid, and I felt the world was leaving me behind because I'd been in the military and I've been to business school, and I could really move, and I did. So there was good and bad, the place survived.

Eric Gleacher: (15:45)

Peterson was good to some degree, he was very smart, he was a great salesman, and Glucksman was a tremendous fixed income guy. He built up a very profitable fixed income business there. But then the whole thing fell apart and they were acquired by American Express. And that didn't work, and then they were spun out. And then Dick Fuld ran it and did a creditable job until the end when somehow he didn't figure out how to get a merger done and let the place survive, and then it caused a lot of problems and was very tough on him and his reputation.

Anthony Scaramucci: (16:26)

Yeah, I had sold my business to Neuberger Berman, and then it got bought by Lehman, so I knew Dick. I worked for him for three years. I still have a, I would say a close relationship with him.

Anthony Scaramucci: (16:38)

But when I was at Goldman, I spent the first seven years of my life at Goldman, and the legendary John Weinberg, who had such great aphorisms, one of them was some people grow, Eric, but other people swell, make sure you're not a person that swells and that you're growing, keep your head on straight. But he said something about Goldman's culture, and I want to transition over to Morgan Stanley for a second, he said, "So my job is to train you to take your six shooters and point them out and shoot out. I don't want you turning these six shooters on each other and shooting at each other and turning yourselves on each other. I want there to be esprit de corps."

Anthony Scaramucci: (17:19)

And you describe Lehman differently than that, what about Morgan Stanley? What was the culture like at Morgan Stanley, as you reference in the book?

Eric Gleacher: (17:28)

It was a great culture. It was teamwork from top to bottom, and it was more homogeneous than Lehman. Lehman was eclectic, it had lots of different kinds of people, which also is a big advantage if you can use it correctly, which Lehman really didn't. But they had a tremendous talent pool.

Eric Gleacher: (17:52)

And Morgan Stanley was a little homogeneous. I was the third person that came in from the outside as a partner back in those days. And you can imagine that you had this firm and we're only three people that came in from the outside. And one of the reasons why I think I succeeded there was because I wasn't a captive of the homogeneity. I didn't grow up there. I'd been in Lehman almost 16 years, and I was, by that time, I was who I was. And I came into Morgan Stanley and I did things a little differently.

Eric Gleacher: (18:36)

And Bob Greenhill, who's running an investment bank was a tremendous influence on the M&A business at Morgan Stanley. And after I was there for a few months he told me he wanted me to run M&A, and so I did, and I did it differently, and I did it aggressively. And did things like I brought Ronald Perelman in as the client for the Revlon deal.

Anthony Scaramucci: (19:05)

You mention that in the book. And that was a unorthodox client for Morgan Stanley at the time, so tell us why that was and tell us why you recruited him in.

Eric Gleacher: (19:16)

Well, I had gotten to know him on other transactions, and Revlon was basically a conglomerate. It had the cosmetics business and then it had three or four healthcare businesses. And the CEO at the time, Michel Bergerac, he was unhappy with the lack of enthusiasm in the stock price and he decided that he wanted to do a management buyout, but unfortunately for him he didn't know what he was doing and he started to approach various companies and see if they're interested in purchasing the healthcare subsidiaries. And two or three of them came to Morgan Stanley and told us what was going on, and I knew right away that there'd be a transaction here and that it was not going to be the one that he had in mind.

Eric Gleacher: (20:12)

So I decided that Ronald Perelman would be a guy who would stick in there and be aggressive enough to try to get this done because he would be interested in cosmetics business. And we did the numbers, and we told him that we thought if it all worked out that he could buy the company, sell the healthcare businesses, and end up with the cosmetics business for nothing. And, in fact, that's exactly what happened.

Eric Gleacher: (20:45)

But I do have it in the book, it was a scary thing for Morgan Stanley. He was definitely unlike any other client that they'd ever been involved in something that was big and highly publicized. And when the executive committee was thinking about whether they wanted to do this, Parker Gilbert, who was the chairman, called me in, and he said, "Eric, we're going to go along with you because I trust you, " he said, "but please don't embarrass the firm." And my life went past my eyes and I said, "All right. I'm a risk taker, and I'm in, but I'm betting my career."

Eric Gleacher: (21:29)

And it turned out that I was right about Perelman. The deal was very tough. He hung in there. Everybody finally gave up, he bought the company. We sold the subsidiaries at the prices or higher, slightly higher than we had estimated, and he made a tremendous deal. And he's owned Revlon for the last, I don't know, 25 or 30 years.

Anthony Scaramucci: (21:54)

Yeah. 30 plus years according to the book.

Eric Gleacher: (21:57)

Yeah. But a lot of people wouldn't have done that. They wouldn't have played their cards like that at Morgan Stanley. But I just did what I believed. And I figured if I stumbled I'd pick myself up and I'd figure out something else to do.

Anthony Scaramucci: (22:15)

Well, I think that's the real message of the book. I mean, the risk, reward, repeat, because sometimes you take risks and it doesn't work out 100% but you got to get back up on your feet, which you demonstrate.

Anthony Scaramucci: (22:25)

Byron Wien was a colleague of yours at Morgan Stanley. I have built a relationship with Byron. He talks about how every person in their adolescence they find something that shapes their approach to life. In his case he was collecting things and he decided that he was going to turn that collection, that stamp collection and a few other things, into stock collecting. And he often asks young people, "Well, what was it from 11 to 18 that you were doing that you were passionate about that you ended up doing for the rest of your life?" What was that for you, Eric? Is that business, golf? [crosstalk 00:23:05].

Eric Gleacher: (23:05)

That was golf, for sure.

Anthony Scaramucci: (23:07)

It was golf. And so golf, that would have been my guess and answered based on the book. So tell us about how golf, in your mind, transformed your business relationships. And this is a question that John Darsie is loving right now, Eric, because all he does is play golf. So tell us about the benefit of it.

Eric Gleacher: (23:30)

John Darsie, when the moment is right, tell your boss that Ed Herlihy, who's your boss's lawyer, spends more time on the golf course than any lawyer in the United States.

Anthony Scaramucci: (23:45)

There's no doubt about that.

Eric Gleacher: (23:47)

Yet many people are convinced that he's the most prominent lawyer in the United States. So there's an argument. Now in my case-

Anthony Scaramucci: (23:55)

Not to interrupt you, sir, he is also the most ethical, has the highest integrity, and I'll say something about Ed which he has said about you, which is obvious, that he loves people. And I think that's something, when you ask people that have worked for Eric Gleacher, what do they say about you, and you can see it here in the books, sir, that you love people. I didn't mean to interrupt you, let's go to the golf question though. Tell us about golf.

Eric Gleacher: (24:20)

Well, like I said, I've moved around a lot. When I was a kid I played baseball. Trouble is you make the baseball team and then you move and the baseball team means nothing. But when I started playing golf when I was 12 I liked it right away. And then when I was 13 I played in my first tournament. And we had moved. I started, we were living in Nebraska, and we moved to Norfolk, Virginia. And I played in a tournament, it was for 13 and under, and I won it, and I still have the sterling silver cup.

Eric Gleacher: (24:56)

And when you're 13 and you have an experience like that you want more. So then about a month or so later I played in the Virginia championship for 13 and under and I won it. And so I got a jumpstart in terms of playing golf, and that's what I did. You talk about 11, 18, I started when I was 12, but I played golf. You learn things about playing golf, you learn about competition, and hopefully, you learn about playing by the rules, you learn the satisfaction of doing something right, winning a tournament, and playing by the rules, and that's something that I think I've brought with me for the rest of my life.

Eric Gleacher: (25:42)

But I won a lot of golf tournaments, a lot of junior tournaments, and I would have never gotten myself into Northwestern where I went to college if I hadn't been a really good golfer. I went, my first year of college, to Western Illinois University in a little town in Central Illinois, and we won the national championship. It was called the NAIA. If you're familiar with sports you'll know what the NAIA is. It's a big deal. There's hundreds of smaller colleges around this country.

Eric Gleacher: (26:13)

So I was 18, we were national champions. That was an experience that I've cherished from then on. I had a great coach. But I decided that if I stayed there I was going to be a golf pro. And I was pretty decent player, but there were others who were better, Jack Nicklaus and a few others. And I said if I can't be in the top echelon I'm not interested. So I got myself into Northwestern, and they took me because they wanted me to play golf there. So, golf had a huge influence.

Eric Gleacher: (26:46)

In business, Anthony, I didn't play business golf. There's a difference. Ed Herlihy doesn't go around knocking on doors saying, "Hey, let's go play golf." But most people play golf. And if you get a relationship with somebody you get to be friends, invariably, you're going to spend time together. You might be skiing or you might go out on a yacht in the Mediterranean or go to art galleries or play golf.

Eric Gleacher: (27:15)

And so, in terms of relationships it's a wonderful thing. I've done it all my life. My wife and I compete all the time. We play even. She's a tremendous player. So it's brought a lot of joy in my life. We play for 10 bucks, and we pay right there on the 18th Green. And so it's good. It's a great thing, and it's had a big influence on me and I met a lot of people.

Eric Gleacher: (27:43)

And when I say reward in the title of the book it means reward those who've helped you. So in the case of Western Illinois University they had a nine hole course and I built the other nine so they'd have an 18 year old course. And we named it for my coach when I was there. And repeat means to be philanthropic and hope that others will follow what you did and repeat it. And those things with me, those were not conscious things, they just evolved. The things I did, it just seemed like the right thing to do.

Eric Gleacher: (28:21)

University of Chicago came to me in the mid '90s and they were building a downtown Chicago business school building and I gave them most of the money for the building. And it was a no brainer, because they had affected my life so much. And so that's the way I've lived, and I wouldn't do it any differently.

Anthony Scaramucci: (28:47)

John, I'm going to turn it over to you. I know you've got a series of questions for Eric too. But I want to hold up the book one more time, because it's a phenomenal book, Risk. Reward. Repeat.: How I Succeeded and You Can Too. But the elemental thing in this book, Eric, that I got out of it is integrity, is to remain true to yourself, be anchored to your core principles, don't waver. Even if you're taking risks you don't want to shade anything in your life, you just want to go straight forward. And you can see it in everything that you've done, sir.

Anthony Scaramucci: (29:20)

You're a big role model for all of us. And I congratulate you on the book. And I know John's got a series of questions as well.

John Darsie: (29:28)

We'll stay on golf for a second just because that's the most fun to talk about. Eric, as a fellow golfer you know that's where we want to stay. But you were a great golfer in your own right, but you also rubbed elbows with some of the greatest golfers in history. You played in all these events with these elite performers. What did you learn about the mentality of great athletes and great golfers in this instance about what it takes to maintain an edge, whether it's on the golf course, in the military, or in business?

Eric Gleacher: (29:57)

Well, the first thing you learn is that they are sticklers for the rules. I give you a really good example, is, I'm a good friend of Raymond Floyd, who's... he won five or six majors, famous golfer. And he won the US Open in 1986, I believe, at Shinnecock. The week before he was playing in the PGA Tour event at Westchester Country Club and he was in contention. He was right up there at the lead and he hit a pot, it didn't go in and it was on the edge of the hole and he just back handed it to knock it in and he missed it.

Eric Gleacher: (30:39)

And nobody saw, you couldn't really tell he did it, but he immediately called a penalty on himself and he lost the tournament by a stroke. But the next week he won the US Open. If he had somehow not done the right thing with the little pot I don't think he would have won the US Open, because it would have bothered him.

Eric Gleacher: (31:05)

The other things I've seen from the pros, and I sure have played with a lot of great ones, particularly Luke Donald is a fellow Northwestern alum, number one in the world for 56 weeks, it's a work ethic, it's a talent, the talent level, the eye-hand coordination is off the charts. And it's just the seriousness of the way they take it, the physical conditioning, the way they play, the way they deal with their fellow competitors. It's very impressive. The PGA Tour is a very, very high level ethical, professional operation.

John Darsie: (31:56)

Yeah, they say you can learn a lot about somebody's character and personality on the golf course. If somebody, it's something so trivial at golf, cuts corners, it certainly tells you something alarming about being in business with him for sure. But I want to transition back to your business career a little bit first, maybe we'll finish with a couple of golf questions. But you led M&A at Lehman and Morgan Stanley, you were almost a pioneer in some ways of this now, what we deem as just normal M&A activity where M&A is just a huge part of corporate strategy to grow.

John Darsie: (32:34)

How has M&A evolved from when you started in the business to what it is today in terms of how frequent and how aggressive people are with M&A versus when you started your career?

Eric Gleacher: (32:46)

That's a really good question, and I've thought about it a lot. Back when, and we're talking about the mid '70s, the Business Roundtable was an important group, all the big CEOs were remembers, and they had an unwritten deal, which was, we're never going to try to take over each other's companies. The world changed, and Morgan Stanley represented a Canadian company, made a bid for an American company, it was very shocking. And at that point I was at Lehman and I had sold and bought some smaller companies.

Eric Gleacher: (33:35)

And my premise was that American businessmen are aggressive, and if they want to build their companies as fast as they can they want to make them as strong as they can, and they want the stocks to do really well. And the way they were going to get there fastest was by acquisition. And I believe that was going to happen, and that's why I founded the M&A department at Lehman, so we'd have a specialized group that could deal with companies. And that all came to fruition, and that was really accelerated in the '80s by Mike Milken in the Milken years.

Eric Gleacher: (34:18)

And the section in the book that talks about the big deals during that period, I put that in there because it's never really been published, the inside story about those deals I think is pretty interesting. And that was a period in American business that had a big effect that goes forward today. And so the M&A business evolved for the basic reasons, I believe, that I said to you that I saw at the beginning, that businessmen want to succeed and they're going to do whatever it takes.

John Darsie: (34:53)

Right. And we talked about culture at the different firms that you worked at earlier. You talked about Lehman, it was sort of the eat what you kill type of environment, but there was maybe a little bit more diversity of people. At Morgan Stanley it was more homogeneous but a more team collaborative environment. If you were to design a culture from scratch for an organization what elements of each of those cultures and other places that you worked or observed, what's that culture that you would look to create?

Eric Gleacher: (35:22)

Well, that's why we had Gleacher & Company. We had this culture, first of all, everybody, when I say everybody, everybody that was with any kind of seniority at Gleacher & Company owned some equity. My secretary owned 1% of the firm. She's still my assistant after 40 years. But everybody did. Not a brand new associate, not an analyst, but a guy who was a vice president above everybody had equity, because that's what I wanted when I started.

Eric Gleacher: (35:59)

I figured I didn't know much about investment banking, but I figured you wanted to own equity, you wanted to be a partner, you want to wake up in the morning and it was your business. So everybody had equity. We had an eclectic group, not a homogeneous group. I didn't think that the homogeneity was necessary to have a teamwork culture. But we had an eclectic group. They were equity owners.

Eric Gleacher: (36:27)

And there's not a single guy that didn't tell me how much different this was than working for a big firm, how great it was to come into work and know it's your business. And that's the way it worked. And it was highly successful. The hardest part, I will say this for me and for any of these boutiques, is succession. It's very tough. And you'll see. Some people have done it right, they've changed their business, but it's really tough. But to have that kind of culture where people own equity, I think, is really critical.

Eric Gleacher: (37:04)

And one of the funniest quotes, Steve Schwarzman and Bruce Wasserstein and I were having a drink one night at a party at Wasserstein's house. And I love Bruce, and he said, "I really like you guys." He says, "I don't understand why everybody hates everybody else at Lehman." And Schwarzman, without hesitation, said, "Bruce, if you were there we'd hate you too." And that was a very perceptive comment about the culture at Lehman. So, you want to have diversity, you want to have women succeeding and so forth, but you don't have to have homogeneity.

John Darsie: (37:48)

Right. And I think a credit to your career is how many people that you helped achieve success on their own terms and inspired them to be great. I want to talk about, before we wrap up with some quick hitter questions, you decided to write this book early in the pandemic, from what I understand, your son helped you edit the manuscript, could you just talk about the process of writing and taking all that life experience and putting it into these pages and really pouring yourself into that project that you wanted to do before you started winding down your career?

Eric Gleacher: (38:21)

Well, I certainly was apprehensive because I had never done anything like that. But I had given lots of talks, at business schools particularly, but elsewhere too. And at the end of whether it was teaching a case or talking about RJR Nabisco or whatever it was, the question was, what did you do to succeed and what do I have to do to succeed? And it's the obvious question. People always ask that. And I thought that I had some interesting things to say and in a narrative.

Eric Gleacher: (38:57)

Some people might get some value out of it. And the books that I always like to read are books like Shoe Dog, Elon Musk biography, which tells what he did. And I'm not comparing what I did to those guys at all, I mean, don't get me wrong. But I think that narratives about business and a person's life and the moves they made, the choices they made, when you say what did you do to succeed, that's the answer. And in a narrative I think a narrative is way more effective than a professorial book based on some kind of research. So that's one of the reasons I wanted to write this book.

Eric Gleacher: (39:38)

So what I did, and my son taught me, he's published four novels and written a movie, and he said he's got to discipline himself, that he cleans his house on Thursday morning and does his laundry and whatever. He said, "You've got to have a schedule."

Eric Gleacher: (39:59)

So I made up my schedule, and that was every day I had to take out my laptop, open it up, and I had to write something. I didn't cure if it was one sentence, I had to write something. And I got into it, and I just... it all came out of me, just poured out of me. I didn't have any notes, I don't have any diaries, but fortunately my long term memory is still pretty good, not my short term memory, my long term memory is good. And I could write this.

Eric Gleacher: (40:27)

And then, of course, with Google search you can do all the facts checking. Anyway, it just poured out of me and then I edited it with Jimmy and we had a ball. And then I found that the editing took as much time as the writing. So it was a good experience for me. It was like a bonus experience. I was so happy I did it.

John Darsie: (40:49)

Yeah. My wife's grandfather is also a great golfer, around your age, routinely shoots his age, he can recall every shot he hit in a member guest or a club championship from the age of 14 to 60, but he can't remember what his wife told him about an hour prior.

Eric Gleacher: (41:09)

Well, that's par for the course.

John Darsie: (41:11)

Yeah, exactly. No pun intended. I want to finish with a couple fun ones related to golf because, yeah, I'm a lover of golf as well, not nearly at the level that you are, but I'm at least in sort of mid single digits. But, what's the best round you ever shot, doesn't have to be score, but where was it, when was it, and what were the circumstances?

Eric Gleacher: (41:34)

Well, that's a question I haven't ever... People ask me what my favorite hole is or whatever, I never have an answer for them.

John Darsie: (41:42)

We'll get to that.

Eric Gleacher: (41:47)

I don't know. I don't have one that sticks out.

John Darsie: (41:52)

No problem.

Eric Gleacher: (41:52)

I hate to give you a non answer, but I really don't have one.

John Darsie: (41:58)

No problem.

Eric Gleacher: (41:59)

I've had a lot of good ones, but there's not one that jumps out.

John Darsie: (42:03)

All right. There's no club championship where you shot 64 and stuffed it in somebody's face?

Eric Gleacher: (42:09)

No.

John Darsie: (42:12)

No problem.

Eric Gleacher: (42:14)

I mean, I've won a lot of them. They're all match play. John, I hate to disappoint you really. That's not the way my mind works with respect to golf.

John Darsie: (42:25)

There you go. Well, what's your favorite hole and/or your favorite golf course?

Eric Gleacher: (42:29)

Well, I have three favorite courses. I get this question a lot. One is the National Golf Links out here, one is Seminole down in Florida, and one is Muirfield in Scotland. Those are my favorite courses.

Eric Gleacher: (42:45)

I will say this, that I did have one experience which was one of the things that Nick Faldo thought it was one of the coolest things he ever heard. I took three of my friends to Muirfield in Scotland, and the daylight over there in summer months is pretty phenomenal because you're way, way up north. And it's light until close to 10:30 at night. So we played 72 holes in one day. We played the British Open in one day. And he won the British Open at Muirfield. So he's very, very partial to it. And he thought it was pretty cool.

Eric Gleacher: (43:27)

And I will say that we had a lot of bets. It was very painful. If somebody quit they had to pay a lot of money to the other three. Nobody quit. But anyway, I shot 69 the fourth round. And that one I do remember. It wasn't a meaningful tournament or anything, but it was a pretty cool experience.

John Darsie: (43:50)

There you go. That sounds like a heck of a day. How many holes in one did you have?

Eric Gleacher: (43:54)

Eight.

John Darsie: (43:55)

Eight? Wow. That's pretty good. There's a lot of guys on tour that don't have eight.

Eric Gleacher: (43:59)

If you play from age 12 to age 81 you get a lot of shots at it.

John Darsie: (44:04)

There you go. Well, Eric, we'll let you go there. It's been a pleasure to have you on. You're an absolute legend, both on Wall Street, in the golf world, and just among your friends. Everybody speaks so highly of you. And Anthony, obviously, has a lot more mutual friends than me, but every time we come across somebody and your name comes up they speak in glowing terms. So, it's an honor to have you on. Anthony, you have a final word for Eric before we let him go?

Anthony Scaramucci: (44:29)

Listen, I mean, among everything, Eric, I just think the way you help the younger people in your career, and you talk about repeat, I hope by and I hope John can pay that forward to a continual stream of people that come into our industry. I often think about that in terms of our summer program and how we can help people that are coming up underneath us, and you were a shining example of that, so I just want to thank you for that.

Eric Gleacher: (44:58)

Well, I want to thank you guys very much for inviting me. You've got a terrific business. I love the SALT portfolio that I looked at, and I know SkyBridge is doing well, and I look forward to meeting you both. My wife and I are still hoping we can go to Scotland for a month in September, but if we don't go I will definitely come to the Javits Center when you guys are doing that.

Anthony Scaramucci: (45:25)

We'd love to have you there. We find a lot of stuff. It's the unfortunate 20th anniversary of the 9/11 tragedy and Jimmy Dunn has agreed to be one of our keynote speakers to talk with us there. So, of course, it would be a big honor for us to have you, sir.

Eric Gleacher: (45:46)

Well, great. Yeah. Now, I need to figure out if I'm going to buy some Bitcoin or not, so anyway.

Anthony Scaramucci: (45:52)

But we got Byron on the bandwagon, okay, he listens to our Wednesday Bitcoin review. And so, as he says, he's a lot younger than Warren Buffett, so I don't think he thinks [inaudible 00:46:03] he's a junior kid compared to Warren.

Eric Gleacher: (46:07)

Yeah. Well, you guys are great, so thanks a lot. I've enjoyed this, and maybe I'll see you in September. If not I'll create some time.

Anthony Scaramucci: (46:16)

And honestly, I hope you go get to play golf, because that's your dream stuff, but maybe October, but if it is September we would love to have you. If you can't make it to Scotland we would love to have you.

Eric Gleacher: (46:25)

Right. Okay.

John Darsie: (46:27)

Eric, thanks again for joining us. Again, everyone, the book is Risk. Reward. Repeat.: How I Succeeded and You Can Too, a fantastic book talking about Eric's career and all the lessons embedded in that career that was so filled with integrity and empowering other people, as Anthony mentioned. But, thanks also for tuning into today's SALT talk with Eric. We love spreading the word about inspiring entrepreneurs like him.

John Darsie: (46:52)

And just a reminder, if you missed any part of this talk or any of our previous SALT Talks you can access them all on our website at salt.org\talks, or on our YouTube channel, which is called SALT Tube. We're also on social media. Twitter is where we're most active at Salt Conference. But we're also on LinkedIn, Instagram, and Facebook as well and ramping up our activity there. But on behalf of Anthony and the entire SALT team, this is John Darsie signing off from SALT Talks for today. We hope to see you back here again soon.