“For better or worse, there's only one me. I just say what I feel based on the facts and the information that I have before me.”

Stephen A. Smith is co-host of ESPN2’s First Take and is ESPN’s most recognizable personality and studio analyst. Before ESPN, Smith was a newspaper beat writer and columnist for 18 years.

Authenticity is critical in connecting with an audience. Combining hard work with that authenticity ultimately drives success. This means falling in the love with the process and committing yourself to the less glamorous behind-the-scenes work that viewers don’t see. Using fear can be a great motivator in driving that commitment to process. “Get caught up in the process… If you’re not enjoying that, you’re not going to enjoy your job.”

The social influence of athletes is greater than ever. Colin Kaepernick represents a major shift in the approach athletes are taking by speaking out on societal issues, particularly racial, that plague the United States. The influence and power that athletes wield will inevitably force corporate America to lean in and serve as allies in the push for change.

LISTEN AND SUBSCRIBE

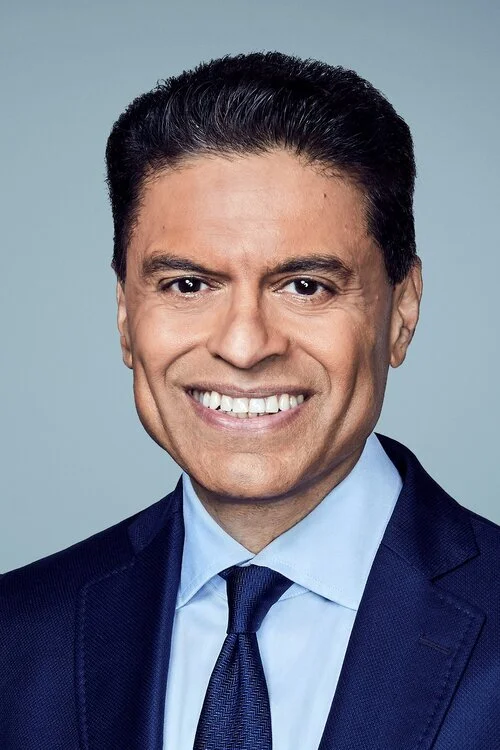

SPEAKER

Stephen A. Smith

ESPN’s First Take & SportsCenter

MODERATOR

Anthony Scaramucci

Founder & Managing Partner

SkyBridge

EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

John Darsie: (00:07)

Hello everyone. And welcome back to SALT Talks. My name is John Darsie. I'm the managing director of SALT, which is a global thought leadership forum and networking platform at the intersection of finance, technology, public policy, and sometimes sports and entertainment which is the direction that we're going in today. We're very excited for today's SALT Talk. The SALT Talks is a digital interview series with leading investors, creators, and thinkers. And what we're trying to do on SALT Talks is replicate the experience that we provided our global conferences, the SALT conference, which we host twice a year, once in the United States and once internationally. And what we're trying to do on these SALT Talks and at our conferences is provide a window into the mind of subject matter experts, as well as provide a platform for what we think are big and interesting ideas that are shaping the future.

John Darsie: (00:55)

And we're very excited today to welcome Stephen A. Smith to SALT Talks. Stephen A. is a former newspaper beat writer and columnist for 18 years, and he's become unquestionably ESPN's most recognizable personality and most visible studio analyst. Since joining ESPN in 2003, Stephen A. has been a fixture on sports center, primarily as the worldwide leaders premier NBA analyst, which included NBA shootaround and NBA fast break. And he also hosts sports center with Stephen A. Smith.

John Darsie: (01:26)

In 2005, he was given his own national television show, Quite Frankly, on ESPN2 with Stephen A. Smith, which was a one hour weeknight show featuring sports, news, opinions, issues, headlines, and interviews, which lasted for 327 shows from August of 2005 to January of 2007. Stephen A. has been the co-host of ESPN2's First Take since May of 2012, which moved to the main network ESPN in 2016. From a clerk and a writer at the Winston-Salem Journal in my home state of North Carolina from 1991 to 1992, to an editorial assistance position at the Greensboro News and Record in 1992 and 1993. From a high school writers position at the New York Daily News from 1993 to '94 to a career at the Philadelphia Inquirer from '94 to 2010.

John Darsie: (02:19)

He started as a college beat writer to now becoming the foremost NBA analyst. And one of only 21 African-Americans in American history elevated to the position of general sports columnists in 2003 in March at that time. Smith considering his success in all three mediums by all accounts is one of the most successful journalists and commentators of the modern era. And again, we're very excited to have Stephen A. with us on SALT Talks today. If you have any questions for Stephen, you can enter them in the Q&A box at the bottom of your video screen on Zoom. And hosting today's interview is Anthony Scaramucci, the founder and managing partner of SkyBridge Capital, which is a global alternative investment firm. Anthony is also the chairman of SALT. And with that, I'll turn it over to Anthony for the interview.

Anthony Scaramucci: (03:07)

John, you left out one thing, he's probably been voted best dressed by GQ at some point in his career. I'm old enough to remember Lindsey Nelson who used to wear those flamboyant sports jacket. Stephen A. welcome to SALT Talks. It's an honor to have you on. How did we go from sports journalism to ESPN? What was the trigger?

Stephen A. Smith: (03:30)

For me, I was breaking stories a lot. I was a newspaper writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer. I started my career as a high school scores reporter for the New York Daily News from '93 to '94. And then I went to the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1994. And in 1998, there was an NBA lockout. The owners had locked the players out in pursuit of a new collective bargaining deal. And at that particular moment in time, everybody was trying to figure out what was going on as negotiations stalled, halted, progressed, et cetera, all different types of things that were going on as you well know that's what happens in that world. And during that particular moment in time, I was breaking a lot of stories. I had sources that were on the executive committee that was on the negotiating committee for both respective sides. I was lucky and fortunate enough to get access to a lot of information that a lot of people didn't have.

Stephen A. Smith: (04:21)

And so when the television networks needed somebody to talk about these things, Comcast locally, mainly in Philadelphia, Bruce Beck, who works at NBC in New York City now at the time was working for the NBC in Philadelphia. And he would have me on, and others would have me on Comcast and they couldn't afford to pay me. I told them, you don't have to, just make a copy of my appearances and give me a copy of it. I used that and I used those appearances and turned it to a portfolio. And then I showed it to CNN/SI, that was CNN Sports Illustrated which was an existing sports network at the time. And CNN had partnered with Sports Illustrated. And I started off. They hired me on the spot and then that developed into a deal with Fox sports Net two years later in 2001. And then in 2003, ESPN came calling. So that's really how the television portion of my career in terms of sports broadcasting actually started.

Anthony Scaramucci: (05:25)

You and I both know, television is not easy, 17 years on television, and you have this very unique style. You reek of authenticity, Stephen Thoreau, budding television presenters, sports journalists, broadcasters, et cetera, are watching today. What would you say to them about the travails of television? What's your experience there? What do you recommend to them and how did you develop your style?

Stephen A. Smith: (05:55)

Well, the last part of that question is always the most difficult for me to answer because I didn't have any kind of broadcasting training whatsoever. My attitude, when I looked at broadcast was that you needed to smile and know how to read a prompter. The latter part was very easy for me, the former, not so much because I'm not a smiler, I'm not the George Foreman type as they say. I don't just cheese for the cameras. You make me laugh, I laugh. You make me smile, I smile. But I'm not going to fake it just to show to give a pleasant view or a pleasure to meet you, that's just not my MO.

Stephen A. Smith: (06:25)

And so for me, when I had the newspaper background, I knew that there was substance attached to me because I was a reporter and I was digging for information. I was in constant pursuit of the truth, not just looking for the license to editorialize and opine. And as a result, because I knew that I had that content, okay, when you get in front of the camera and the lights come on, there really is just all I had was for me to be me. So the manner in which I speak, the way I articulate myself, the way I disseminate information, et cetera, that has always been my way.

Stephen A. Smith: (06:55)

And as a result, it just stuck. So when people ask me, "How can I do this? How can I be like you or whatever?" I'm like, "Well, for better or worse, there's only one me. I just say what I feel based on the facts and the information that I have before me. This is where I stand. This is how I feel in the moment. I'm not afraid to correct myself. I'm not afraid to admit I'm wrong on a rare occasion that I believe that I am." And that's just my mentality.

Stephen A. Smith: (07:22)

And as long as you're coming from that perspective, there's a level of humanity that's attached to your willingness to admit that you're wrong or willingness to be real and authentic because what I'm trying to convey to the audience, I want them to know they can trust me. And what I mean by that is not just trust my information, but trust that I believe what I'm telling you. If I need to be corrected, I need to be corrected, but I'm not faking anything. I'm coming at you from that perspective. And because of that, that I believe is what has been able to propel me.

Stephen A. Smith: (07:51)

So when I look at people in this industry, I would tell them all that glitters isn't gold. Be ready to put your head down and go about the business of doing the work. Don't get caught up in the sizzle, get caught up in the work. Don't get caught up in the culminating point, the end result. Get caught up in the process because there's usually a long and lengthy process that comes before the actual accomplishment. And if you're not married to that, if you're not enjoying that, then you're not going to enjoy your job.

Stephen A. Smith: (08:22)

And the difference between most people's job and my job is when I'm speaking to people, hundreds of thousands if not millions, actually at this point in time of my career, it's tens of millions of people per day. The bottom line is, is that if I don't enjoy it and I'm not passionate about it, and I don't feel what I'm talking about, the first people that are going to notice is that audience. And before long, they'll be gone, looking to find someone else that inspires them or that ingratiates themselves with them to a point where they're willing to gravitate towards them.

Anthony Scaramucci: (08:57)

All right. But you've got this unique thing going, you know and I know it, and God bless you for it. For me, I was getting hit in the head with a wooden spoon by my Italian nana. I had to fight it out at the dinner table on Sundays with my cousins, and that was my media training. Where did you get the media training from? Was it from your family?

Stephen A. Smith: (09:19)

Well, if you put it that way, I mean, that's easy. I'm the youngest of six. I have four older sisters that were living with-

Anthony Scaramucci: (09:25)

I'm surprised that you have a 32 inch waist, if you're the youngest of six [crosstalk 00:09:30].

Stephen A. Smith: (09:30)

It's actually 36 and counting is going down. But the point is, is that I've got four older sisters that beat me up figuratively. Literally at times, they were my litmus test per se. A few of them, no sports, my dad-

Anthony Scaramucci: (09:46)

You've taken all of that out on the Dallas Cowboys, right? All of that like pop.

Stephen A. Smith: (09:50)

For me with the Dallas Cowboys, it's really not about them, it's about their fans. I think Dallas Cowboys' fans are the most disgusting nauseated fan base in American history. They make me sick and there's nothing in life that makes me more happy when it comes to sports than to see them miserable. I think Dallas Cowboys' fans are the worst human beings a lot. It doesn't matter if they go one in 15 and the season ends on a January 5th at 7:00 PM. By 7:10, 7:15, they'll be telling you, "You know we're going to win the super bowl next year?" They don't take any time to smell themselves at how stink they are. And that's what I can't stand about Dallas Cowboys' fans, which is why I like rubbing their nose into it.

Stephen A. Smith: (10:29)

And I must be thankful to the Dallas Cowboys, because I like Jerry Jones. I really do. I like Jerry Jones a lot. And the Cowboys allure the $5 billion franchise brand that they are. Major props to him. But because of their fan base, nothing pleases me more than to watch the Dallas Cowboys lose, especially during the holidays. I don't like it when they win. They lose in September, October, but they'll win in January, February. No, I want them to lose around Thanksgiving and I want that to flow right through Christmas so the whole holiday season is ruined. I don't wish anything like that upon anyone on this planet, but the Cowboys' fans.

Anthony Scaramucci: (11:09)

I'm going to take mayor of Dallas off of your second act career. No problem. You still-

Stephen A. Smith: (11:16)

He might not be a Cowboys fan. He might not be a Cowboys fan for all we know. You never know.

Anthony Scaramucci: (11:22)

I don't know, but you might be governor of Texas. I mean, because some of the Texas is antidotal suit. Well, let me ask you this because this is something I absolutely love about you. Of course I've been watching it like everybody else for the 17 years. You take absolutely no bullshit ever from anybody. You call people out on it on the air, you interrupt them when you know that they're giving you malarkey. And so how did you get that detector going? Is that from your sisters too? Where did that sound detector come from?

Stephen A. Smith: (11:54)

That's the streets. Born in the Bronx, raised in Hollis Queens. Walking the streets like thank God I had the most wonderful mother on the planet I didn't got arrested. That kept me off the streets in terms of me engaging in any illegal activity. But I certainly was surrounded by, in terms of the people that I knew. I grew up with drug dealers. I grew up with drug runners. I grew up with guys that were relatively violent or what have you. When you from the streets and you have to survive in that stratosphere, particularly when you're operating on the right side of the tracks, instead of the wrong side of the tracks, you've got to have your sense and you've got to be alert at all times. And you got to be able to decipher what's real from the BS. People trying to set you up, trying to put you in compromising positions and things of that nature. You got to be alerted to all of that.

Stephen A. Smith: (12:45)

And so growing up at a very young age, I knew that if I needed to survive in the streets, Ronald Reagan once said it best if I remember correctly, trust but verify. If I remember, I think that came from him and that's been my mentality a lot. I'm fortunate and blessed to have great friends and family members in my inner circle who are tremendously loved by me. They're very knowledgeable. They're very smart and what have you. But even with them, I'll double check what they have to say. I'll triple check what they have to say. That's just my MO and it comes from Ronald Reagan.

Anthony Scaramucci: (13:23)

In my neighborhood, out on Long Island, there was a prolific drug culture. My uncle owned a motorcycle shop. I worked in that motorcycle shop. I've learned how to shoot craps at age 11. I learned how to drive a three speed Dodge van at age three. So everybody who I'm running money for right now is redeeming on my phone, which is fine. But I knew despite that rough crowd, that I was going to try to go straight and I was going to try to do the right things and stay away from that stuff. You did too. So there was a moment, there was a seminal moment where that popped into your head. That little bubble popped into your head, Stephen, you said, this is the where I'm going. And so offer some guidance and perspective to some of the young people that are listening to us right now. What happened? Why did that bubble pop into your head and catalyze you in the direction that you're in?

Stephen A. Smith: (14:15)

Well, a couple of things. Number one is love. The love of your loved ones closest to you who have your best interests at heart. That definitely goes a long way because even those who are operating on the wrong side of the tracks, they'll tell you, you don't need to be there. I have literally had drug dealers that would sit around and say, okay, this guy is trying to get a basketball scholarship. He's going somewhere. Do not bother him. And would instruct the people working for them do not bother him. Let him shoot his hoops at 192 park and Hollis, Queens, New York on 204th street. Let him shoot his 200, 300 jumps shot. Do not bother him. And then when it was time for them to do their business, they would say it's time for you to get on out of here. So that was love right there.

Stephen A. Smith: (14:56)

Number two violence. Because I saw somebody get gunned down right in front of my face. He got his head blown off right in front of me when I was 10 years old. So that definitely went a long way and we sort of knew his background and what he was doing. And so it crystallized in your mind that if you're doing these kinds of things in all likelihood, that's how your life would probably end. And you have to ask yourself whether or not you wanted that. And then for me personally, again, I keep bringing up my mother because she worked so hard and she made so many sacrifices. When you have someone that you love as dearly as I loved my mom, you want to make them proud, you don't want to disappoint them. And so you got to think about those things as you're striving to be something and to make something of yourself.

Stephen A. Smith: (15:42)

And a lot of times when we see youngsters out there, they've got this, what coach the John Chaney, the legendary coach John Chaney, who used to coach at Temple University, their basketball squad. He called it the microwave society. He despised the mentality that youngsters have wanting everything now and wanting everything to leapfrog the process without really working and maneuvering your way through it. And what I would encourage young people to do is not only should you go through the process, you should enjoy it because it elevates your level of knowledge. When you have to go through a certain terrain, a minefield, in order to get to where you want to go, then guess what? Once you get there, first of all, no one can question you because you've got there the right way. And number two, nobody can question your knowledge because you have experiences that most people didn't have. Look at you, Anthony, and all the things that you've been able to accomplish in your career and in your life.

Stephen A. Smith: (16:36)

The number one reason people should recognize that you're on TV a lot of times talking, when I see you on CNN and other places, is because of your knowledge and experience. It's not just your ability. Yeah, you have the ability, but you have a knowledge and a level of experience that comes along with it. So when you're talking, I see people listening to you and want to debate you. But then there are other times you're talking and people instinctually know to shut the hell up because you've been places they haven't been. That experience really buffers and augments you to another level that will ultimately enable you to speak with a level of authority that could ultimately make you successful at whatever you do. And that's my philosophy.

Anthony Scaramucci: (17:19)

Let me tell you something, Stephen, I'm going to be clipping that and playing it for my wife who happens to be the most expensive makeup artists in the world. She thinks it's all about her makeup is the reason why I'm on television. I want to make sure-

Stephen A. Smith: (17:31)

No, no, wait a minute. I got to give you a piece of advice, let her believe that.

Anthony Scaramucci: (17:35)

Okay. All right. I take it back. [crosstalk 00:17:39] because she loves Stephen. You cut this piece out.

Stephen A. Smith: (17:45)

This is the way.

John Darsie: (17:46)

We'll cut that.

Anthony Scaramucci: (17:48)

Of course we're not cutting anything, we're doing this live. The thing I want to say to you that is so admirable of you is the grounding. I can feel the grounding wire and you have soared my friend and congratulations to you for that. And I hope you continue to soar to ever higher and higher Heights, but there is a grounding wire. You can see it on the air. I can see it right now in this interview. Is that coming from your mom? Is that coming from your spirituality? Is that coming from your grace in terms of your gratitude at the way life has unfolded for you? Tell us about your grounding wire and how you've been able to maintain.

Stephen A. Smith: (18:29)

Well, it's all of the above, but it starts with mama. Because mama was the one that worked hard. Mama was the one that worked 16 hours a day, seven days a week, had one week vacation a year, just to feed us. Even though she was married to my dad for many years. Let's just say he wasn't as responsible as he should have been. And that put a lot of the onus on my mother's shoulders. And so to witness that, and to witness her struggle, first, it was an aspiration not to disappoint her. Then ultimately it became an aspiration to make her proud. And then in the process of doing that, then you run into other people along the way who gravitate to you because of the character she helped instill in me.

Stephen A. Smith: (19:11)

And so then, from a spiritual perspective, I go to Christian Cultural Center in Brooklyn, New York. My pastor is A.R. Bernard. He's a phenomenal, phenomenal, man. I love him dearly. He's always been there for me. And he's somebody that I trust implicitly. And so to have that kind of guidance, definitely helps. Then you think about the family members that you have, that my mother influenced, the people in the neighborhood that I grew up with, that I know that I could trust. Because it's not always about people being the way you want them to be, it's about them being their unapologetic selves. They don't disguise it from you, you know who they are. And as a result, you can trust them to be exactly who you know them to be. And there's a benefit to that as well.

Stephen A. Smith: (19:56)

And so all of those things come together and it helps develop you into the adult that you aspire to be because the challenges that inevitably are going to come your way, you know that you're prepared to deal with whatever, because you've seen so much of it, because you've been so thoroughly prepared by the people you love and the people that love you that are a part of your inner circle. They buffer your knowledge. They buffer your conscience. They buffer a lot of different things that help make you better at what you do.

Stephen A. Smith: (20:25)

So when I'm grounded, I'm grounded because of them as well. Because just the same way I feel about them, they feel about me. Because there's a trust there, they can tell me anything. They could tell me when they think I'm wrong. They can tell me when they think that I don't know what the hell I'm talking about. They can tell me when they say, excuse me, you need to do this, you need to do that. They might lecture you. They might pester you. Sometimes you even want to listen to them. You don't want to hear it. But in the end, when you know they have both knowledge, and two, a spirit and a heart about them when it comes to you that makes trustworthy, you end up wanting to listen to them because you value them.

Stephen A. Smith: (20:59)

The people I surrounded myself with are what keep me grounded right now. Because even though I'm Stephen A. to them, I'm Steve or I'm Stephen. I'm not Stephen A. I'm the same dude that grew up in Hollis. Yeah, I might be a little bit more successful and certainly more recognizable. But the bottom line is, they will not tolerate chillings from me, because they love me just the way that I was.

Anthony Scaramucci: (21:24)

Well, I mean, listen, I totally identify with that. I live two miles from where I grew up. I'm one of the few people that went to college in my family. Everybody's named Anthony because we're Italian. That's my great grandfather-

Stephen A. Smith: (21:37)

You know my middle name is Anthony, right?

Anthony Scaramucci: (21:38)

Right, right. I know that. Of course I know that. Come on, man. Stephen A. But let me just say this, we got Anthony Auto Glass, we have Anthony Clamor, we have Anthony Pizzeria. I'm just having to be Anthony hedge fund on Christmas Eve.

Stephen A. Smith: (21:52)

I'm quite sure they would grab the hand of the hedge fund.

Anthony Scaramucci: (21:56)

Trust me, they treat me like, Anthony, you know what? Low on the bottom of the shoe, which is all good by me. Before we get back to sports though, I got to ask you this, I'm really identifying with this conversation. And it's a Tyson thing. Everybody's got a plan until they get smacked up in the face, had setbacks. There's no way you're getting to be Stephen A. from Stephen, Hollis, Queens to where you are right now without setbacks. So describe your resiliency. Describe the methodology behind your resiliency and describe all of that positivity that has gotten you to where you are.

Stephen A. Smith: (22:35)

You call it positivity, I wouldn't. Matter of fact, fear is a great, great motivation for me. Fear of failure, fear of disappointment, fear of having to live with myself knowing that you may have failed because you didn't give it you all.

Anthony Scaramucci: (22:55)

Fear of poverty, Stephen. I've had the fear of poverty thing going my whole life.

Stephen A. Smith: (22:59)

And fear of poverty is a big thing. And I'll tell you something right now. The latest, I mean, obviously I grew up or what have you, but the latest was in 2009 ESPN elects not to renew my contract. We had a contract dispute. They elected not to renew my contract. And for a full year, I was unemployed living off of my savings. More importantly, even though I thought I had established myself in the business, clearly I hadn't because no one was knocking on my door, willing to hire me to be in television. And when you got to taste a bit, I made my first million dollars in 2005, thinking that I had arrived and what have you.

Stephen A. Smith: (23:38)

And then all of a sudden, just four years later, everything, and I do mean everything, falls apart at the time that I was expecting to be a daddy. It was incredibly scary because I grew up poor and I did not want my children ever grow up poor and struggling and starving and things of that nature. And I was literally, literally scared to death. And so that level of fear. For some reason, I put my head down, I do what I always do. I put my head down, I went to work. I pounded the pavement. I was tenacious. I persevered. And then I got back. And when I got back two years later at ESPN, because after one year I got hired by Fox Sports Radio to do their morning drive show for a year. And then after that, ESPN can call me again.

Stephen A. Smith: (24:25)

And I remember that my boss, was my boss to this very day, my immediate supervisor, his name is Dave Roberts. Phenomenal boss. I told him I'm taking over. I said the fall from grace, if you thought I couldn't be more motivated than I was before, watch out now. And so he always laughs and reminds me of my work ethic, my dedication. I remember that one of the big bosses, his name was John Wildhack. He was an executive VP over production for ESPN. He's now the athletic director at Syracuse University. And he introduced me to talk to the football team one time. And he said, I've been in the business for 35 years. I'm about to introduce our next speaker, talking about me. He said, he's the first man in my 35 years that I had to make, take vacation. The dude doesn't stop. And that is a reputation I love to have. When am I off? When the job is done. When am I finished? When the job is done.

Anthony Scaramucci: (25:30)

I love it. I love it. And I'm going to tell you something funny about Dave Roberts. I'm on CNN on the morning show and I'm doing it from my home studio, of course, because of COVID. My wife comes down with the cordless phone and she says, "Do you know a Dave Roberts?" And I said, "No." And she said, "Well, there's a guy by the name of Dave Roberts on the phone. He wants to talk to you." I'd just gotten off the air. I pick up the phone. I said, "Hello. "He says, "I'm Dave Roberts from ESPN. I got your phone number by looking it up on Google," there's my phone number. He's cold calling me, "Because I just want to tell you man, you're awesome on television and keep up the good work." And that's Dave Roberts, am I wrong about that? Or no?

Stephen A. Smith: (26:13)

That's him.

Anthony Scaramucci: (26:14)

And now him and I probably talk once or twice a month about what's going on in the world and sports and life and everything else.

Stephen A. Smith: (26:22)

He's a winner. He's a winner. Whatever he touches, turns to gold, as far as I'm concerned.

Anthony Scaramucci: (26:27)

He absolutely loves you. I have to turn it over to John Darsie in a second because if we don't get these millennials in, we don't get the ratings that I want. I got to let Darsie in in a second. But I just got to ask you two more quick questions. I want your favorites for the Super Bowl, you've been thinking about it. Who are your favorites?

Stephen A. Smith: (26:51)

Well, I had Tampa Bay at the beginning of the season, but right now I'm thinking the Kansas City Chiefs versus the Green Bay Packers.

Anthony Scaramucci: (26:58)

All right, that'd be an exciting game. Second question, of the leagues, COVID-19 who handled it the best, of the pro leagues?

Stephen A. Smith: (27:08)

Without a question the NBA, that's an easy one right there. When you consider the sacrifices that the players made combined with the team and the league itself, how organized they were. They went like the last couple of months or so, I'm talking about that whole time in the bubble. They didn't have one single positive test. It was unbelievable. You have players holding other players accountable. One player snuck some woman in there, and he didn't even get a chance to test positive. They sent them home. They didn't play. The NBA was on their game. The players were on their game. And I can't say enough for two people. I can't say enough. Of course, Adam Silver, the commissioner, did a phenomenal job. Of course, Michele Roberts and the Players Association, she's the executive director. They did a phenomenal job.

Stephen A. Smith: (27:53)

But two people really, really stand out. Chris Paul, who is the president of the Players Association and perennial all-star future Hall of Famer. This guy in terms of his willingness to play and play to the level that he played while at the same time, negotiating deals and stipulations on behalf of the players to make sure play could resume. You just can't say enough about the phenomenal job that he did and the level of credit that he deserves.

Stephen A. Smith: (28:20)

And more importantly, just as important is LeBron James. We can slice it any way we want to. This is the greatest play in the world right now. He ended up winning a fourth championship, but to be stuck in a bubble for 96 days, to be away from family loved ones and friends, to play the way that he played and keep his team as motivated and as focused as they needed to be in order to capture a championship and still carry that Baton while bringing attention to the George Floyds of the world, the Breonna Taylors of the world and others when we were talking about African-Americans and law enforcement officials, you just can't say enough about all the stuff that was on LeBron James' shoulders and the way that he handled himself and his team, enabling the Los Angeles Lakers to walk away with the 17th title in franchise history. You just can't say enough about it.

Anthony Scaramucci: (29:14)

Well, I'm going to turn it over, but I just let if you ever come to my office and visit me in New York, I've got a huge picture of Jackie Robinson in my office. And on the other side of the office, I got Muhammad Ali. Who are two of my heroes because they were originals and you know how much Jackie Robinson took to be in the Major Leagues. And a lot of the peace and social justice that we have found in our society has been moved by men and women of sports who had that level of courage and had that level of tenacity. Of course the champ, when I think about the GOAT, Muhammad Ali, what he was like in the sixties and what he stood for which everyone is still fighting for today. I got to turn it over to Darsie here, Stephen A., but if we get close, I'm going to start calling you Anthony, after your middle name. You'd be known as Steven Ant. All right?

Stephen A. Smith: (30:08)

No problem.

Anthony Scaramucci: (30:10)

Go ahead, Darsie. I know you've got some audience participation questions.

John Darsie: (30:12)

Yeah, I couldn't let Stephen A. out of here without talking a little shop with the GOAT, when it comes to TV personality. I grew up watching SportsCenter. It was appointment television for me when I was younger. Sports media has evolved with the advent of the iPhone and on-demand clips. Stephen A., in my opinion, has become the appointment television for ESPN in 2020, and even prior to this.

John Darsie: (30:39)

I want to build on that conversation about social justice issues a little bit and LeBron James. I always find that amusing that sometimes the hate that's directed at him for certain things that he does and people accuse him of being inauthentic. But I think as much as anyone, he's given other athletes the courage. You had people like Colin Kaepernick who stepped forward as well, but given players the courage to really make social justice a big part of their identity. Do you think that we're at a tipping point in our society today? And do you think athletes have led us to that tipping point where we're really going to see some of these social justice and racial justice issues start to turn and reach a more equitable society?

Stephen A. Smith: (31:19)

Well, my direct answer to that question is that we better be making the turn. We better be moving in that direction. Because if not, athletes today are more empowered than ever before. And as a result, there's going to be a hefty price paid by corporate America and beyond, make no mistake about it. What a lot of folks don't realize is that they keep forgetting the communities these guys come from. You might become rich and famous. You might become wealthy, but to a modern day athlete in particular, you never forget home. Because if you do, they may not forget about you, but you'll be a pariah. And nobody wants to feel like a pariah from their own hometown. You just don't want that. And when I say hometown, I'm talking about the streets that you come from, it could be inner city streets across the United States of America.

Stephen A. Smith: (32:07)

On many occasions, I've often told white bosses this, white folks come to work with a job to do every day. Black folks come with a responsibility. When Trayvon Martin got hot by George Zimmerman, the black community looked at me and said, "Stephen A., you got to talk about this. Stephen A., you got to say this. You got to say that." Now, I never feel compelled to say what anyone wants me to say. I say what the hell I want to say, what I feel, but I do feel compelled to make sure their voices are heard. I do feel compelled to make sure that whatever message the collective whole of our community has that they want disseminated. That I make sure that I express that and disseminate that to the masses. So the masses will know.

Stephen A. Smith: (32:51)

I feel no obligation to agree with it or disagree with it, but I do feel an obligation to make sure that people from our community are heard. And I think if I feel that way, imagine how some of these athletes feel. Now they're not on national TV every day, and I get that, but they do have social media accounts, Twitter, Instagram, Facebook in the millions, in some cases, the tens of millions, in some cases, over a hundred million. And so their reach is incredibly extensive. When you combine that with the wealth that they have at their disposal or rather, I like to say rich, because to me, wealth and riches is two different things, but these guys are rich. And so they've got enough cache, enough muscle in the public eye to really, really make some noise and resonate in a very, very profound fashion.

Stephen A. Smith: (33:38)

I would caution corporate America to make sure they hear that loud and clear and they operate accordingly. Because one thing is absolutely positively true, the days of these dudes being timid and shy and apprehensive have rapidly come to an end, at least for some of them. Too much influence in social media and beyond, too much influence with the younger generation is what they have to sit idly by and ignore some of the transgressions that have taken place in our society. That's what they were doing this summer. That's what they were doing since COVID took place. That's what they were doing since George Floyd got killed and what have you. And I don't anticipate that that's going to stop. If they're able to look at America and say, you haven't changed one bit, you're the same damn way you've always been. If America elects to be that way, there's going to be a problem.

John Darsie: (34:32)

Yeah, we've had really successful prominent African-American business people on this program. And we've heard them talk about how they don't always love having to speak up about these types of issues. Throughout their career, they attribute some of their success to just blending in and not having to consider themselves different than everybody else, but today they have no choice. They feel like, you know what? I have to lift up my brothers and sisters and I have to speak out and I have to be active on these issues because I have no choice.

Stephen A. Smith: (35:03)

It's important that everybody also understands why. It's not just because of that, it's because the choice of being quiet no longer exist. That's the real issue here. So because you are now compelled to speak up, that means you have to take a side. Now, you can take the side [inaudible 00:35:25], or you could take the side of your community and speak up and speak out about issues relevant to your community. These athletes find themselves in that untenable position and they have no choice, but to embrace it, some love it because they love having a voice. And they finally get an opportunity to express themselves knowing millions are going to hear them. Some are very reluctant to do it because they know how they feel is going to cost them in some capacity, either in corporate America or it's going to cost them a price with their own community.

John Darsie: (35:57)

Right. I want to shift gears a little bit to talk about sort of the business of sports and the business of sports media. Disney just announced they're giving you another show on their ESPN+ streaming service. We're seeing this massive movement towards streaming. You have Netflix that's disrupted the entire entertainment industry. Warner Media announced they're going to start simulcasting their movies on HBO Max. Disney+ has obviously been a great success at your parent company. How do you think we're going to continue to see sports media evolve in a world where media rights are so valuable and expensive and so entertaining people in different ways on different platforms is going to be so important.

Stephen A. Smith: (36:36)

Well, I think you're going to see cable suffer to a degree because outside of live events, why not go direct to streaming? Why not go direct to consumer? It's a more feasible and profitable way it appears to go about doing your business. When you have to pay cable operators and things of that nature, that's going to compromise your bottom line to some degree, which is why I think you've seen layoffs across the board everywhere.

Stephen A. Smith: (36:57)

As it pertains to me, my show is going to be called Stephen A's World. It's going to be the lighter version. I'm going to be looking to have fun and make people laugh and enjoy themselves and have a good time because we all know I'll bring the heat on ESPN, whether it's on SportsCenter, whether it's on First Take, whether it's when I'm hosting my own NBA show that Stephen A. is going to always be there. But there is a lighter, more fun side to me, sort of that late night feel because my ultimate aspiration is to actually own the late night show. The way Arsenio Hall and Jay Leno and David Letterman and guys like that ones did.

Stephen A. Smith: (37:29)

My ultimate aspiration is to actually do that one day. So that's an aspiration that I have. And I think that this is going to go in the direction of showing my willingness and hopefully my ability to do such a thing. But again, to answer the question directly, when you see these athletes getting involved, athletes are exploring the business side of things. They understand content a little bit better than they've been given credit for because they bend the content providers, not just because of their plate on the court or field of play, but the interviews that they've done, the statements that they've made, the way that they've resonated in social media and beyond. The means that they've seen put out there in social media and what have you.

Stephen A. Smith: (38:10)

It gives you the impression that you might have an elevated level of knowledge when it comes to content providing. And as a result, it makes you gung ho about sticking your fingers into that bowl to sort of see where that will take you, because we all know that no matter what people make in front of the camera, there's always people making a lot more that are behind the camera. And so these guys see those kinds of things transpire. You also have to take into account, the individuals that they run into. Go to a Lakers game, you'll see folks from Disney, you'll see folks from Fox and other networks. You'll see directors, producers in Hollywood and beyond. When these folks go about the business of ingratiating themselves with you and allowing you to do the same and you make those kind of connections. And then you see the kind of things that they want to do in the world of television streaming and beyond.

Stephen A. Smith: (39:03)

As it pertains to content, it gets you excited about the possibilities of what you might be able to do if you were so lucky to be afforded such an opportunity. So those kinds of things, these players are thinking about because they want a stream of revenue. Remember, our careers going on. I'm 53. And as far as I'm concerned, I'm literally barely in my prime. I got about 15, 20 years left in this business as far as I'm concerned. You guys, the same thing. These players, most guys careers are over by 30. They're lucky enough, some at 35, some football players, the Tom Bradys of the world, Drew Brees of the world are very fortunate to be in their forties.

Stephen A. Smith: (39:45)

Well, what the hell are you going to do with the rest of your life? You start thinking about those things. And that's why they venture into this business realm to the degree that they're doing so. Because they're looking for an outlet, they don't have to step away. From the cheers, the adulation and all of these other things to being obsolete. They want to play different roles. They don't mind stepping away from the cheer, the crowd, but they don't want to step from stardom to be an obsolete. That's a bit too extreme for them in the stomach. And as a result, that's why they are hungry to do things in this business. And I don't blame them.

John Darsie: (40:19)

All right. Switching gears again, I want to talk about leadership a little bit. I'm a native North Carolinian, but you're a New Yorker. Anthony's a New Yorker. You guys have suffered through many decades of subpar performance from your professional sports franchises. I'll leave it there. It brings me to a question. We have a lot of corporate executives that tune into SALT Talks and so relating business leadership and sports leadership and sports business leadership, what in your observation, viewing up close the dysfunction of some of the New York franchises and also having relationships with the very successful franchise owners and leadership and those organizations, what are the characteristics of a good and bad franchise in sports?

Stephen A. Smith: (41:03)

Well, first of all, the bad characteristics are people that hate working for you, for a multitude of reasons. You cut corners. You take shortcuts. Winning is not your top priority. Mediocrity is not something that you appear to have a problem with. Those kinds of things definitely give you a sour taste in your mouth if you're a professional sports team, a professional athlete, or what have you. You really don't want to have much to do with that. Those that have winning situations, yeah, it's associated with excellence, but it involves the excellence of the culture as opposed to the bottom line.

Stephen A. Smith: (41:42)

If you're a performer, what you want to do is look at your superiors and say, "I have everything I need to win. It's on me." You're not running from the challenge of it being placed on your shoulders. You're despondent in fact, when you're in an environment that you don't deem to be conducive to winning. It's an incredibly, incredibly tough situation to be in when you know that you could be doing better and your product could be doing better, but the decisions by the higher ups is what's holding you back. Because when you see something like that happen, you don't want to hear them talk to you about winning because you know that they could snap their fingers and make decisions that are conducive to winning, and they just refuse to do it. And so as a result of that, that's certainly not a winning formula. That's something to take into consideration.

Stephen A. Smith: (42:31)

But what a winning formula is, particularly as it pertains to bosses, inspiring people to want to work for you, to want to work with you. Being committed to excellence, showing them that it's not just about your excellence, it's about theirs as well, and how we all rise together. Magic Johnson was famous by telling his teammates, man, we all should. "You could see me on the commercial doing something for Converse or McDonald's or something like that, but trust me, endorsement deals are going to come your way. Popularity is going to come your way, the perks and the cache that comes associated with success and winning they're going to come your way."

Stephen A. Smith: (43:09)

And he was unapologetic about it. And he was very sincere and projecting that kind of imagery and it came to fruition. They saw that he was right and then inspired them to perform with him and for him even more. When you look at Pat Riley and South Beach with the Miami Heat, well, he's got rings. LeBron James wants to depart from Cleveland and he comes to Miami. And even though he had already talked with Dwayne Wade and Chris Bosh about joining forces, when he sat down with the Miami Heat and everybody had presentation and films and all of these other things to appeal to LeBron James, Pat Riley, sat in front of him and put down five rings and said, "Do you want one of these? Yes or no?" And that's what it took.

Stephen A. Smith: (43:54)

We taught that to the business world. Larry Bird's got a group of 13 other people, and they're trying to buy the Charlotte Basketball franchise at the time. The asking price is $300 million. And Larry Bird's group has about 250, 260, they're about 40 million short, but he's Larry Bird. And they want to give them time to get the assets necessary in order to buy the franchise, et cetera, et cetera. All of this stuff is being talked about. But Bob Johnson, former owner for BET knows Jerry Colangelo. Both of them went to the University of Illinois. There was a connection there. What happens, Jerry Colangelo, owner for the Phoenix Suns at the time, he's got an in with the NBA owners because he's been associated with the NBA since the sixties. So he gets Bob Johnson to the negotiating table.

Stephen A. Smith: (44:46)

And Bob Johnson sits at the negotiating table and tells these board of governors, which consist of each owner for the team or the chief executive they choose to appear as their board of governor. And he shows up and he said, "I appreciate the greatness of Larry Bird. He's done a lot for the NBA. Very, very special. But last time I checked, this was a business deal. And here is my financial portfolio." And his financial portfolio was worth $1.7 billion. And the next words out of his mouth was, "Who do I cut the check to?"

Stephen A. Smith: (45:20)

We have to understand, it's networking. It's connections. It's all of that stuff too. But at the end of the day, what's the rule of the game that you're playing. He knew the rules and it was finances. Pat Riley knew the rules, it was rings. Magic Johnson knew the rules, it was competing for and putting yourself in a position to win championships. And they made sure to articulate and aluminate that agenda for all to see. Showing that it wasn't just a benefit to them, but to the very people they were trying to appeal to. And as a result, everybody bought in because of it. And that's why they are who they are, and most of us aspire to be who they are.

John Darsie: (46:05)

And Bob Johnson proceeded to name the team after himself, the Bobcat's and then we [crosstalk 00:46:14]. And then we flipped it to our good friend, Michael Jordan, who I still think Michael is going to turn it around. He's a North Carolina guy like me.

Stephen A. Smith: (46:18)

I hope so. He's a friend.

John Darsie: (46:21)

So last question, we can't let the preeminent NBA analyst in the world leave without giving some predictions for the season that starting next week. Who do you think wins the NBA championship this year? Lakers are going to repeat? [crosstalk 00:46:35].

Stephen A. Smith: (46:35)

You had a champion and you had the best off season. And that off season, Dennis Schröder and Marc Gasol and Montrezl Harrell. I mean, my goodness, they had the best off season.

John Darsie: (46:50)

Horton-Tucker looks like a player.

Stephen A. Smith: (46:52)

Yeah, he does.

John Darsie: (46:53)

So what are some teams and players that may be not on the mainstream radar or people that follow the NBA less closely that you think are going to take a big step forward this season?

Stephen A. Smith: (47:03)

Listen, in the Western Conference, the elite teams are the Lakers, the Clippers, the Dallas Mavericks. They definitely stand out. There's no question about that. Houston is taking a step back because Russell Westbrook is gone. James Harden doesn't want to be there. A trade seems eminent at some point. So they're not going to be the same, but in terms of an up and coming team, look out for the Phoenix Suns, Devin Booker is a star. You've got Deandre Ayton and others that can play on this squad. There's something special. Don't ignore them. Chris Paul is there now as well. So we can't ignore that.

Stephen A. Smith: (47:39)

You got to pay attention to the Warriors. I know Klay Thompson is out for the year, but Steph Curry has returned. They drafted this kid, James Wiseman and number two out of Memphis, even though he only played about three games. They still have some of the pieces. They picked up Kelly Oubre. They've got Andrew Wiggins. This kid Paschall that was on a bench and averaging 14 a game last year. He's going to play an integral role as well. When you consider that, they should be a playoff team. And when you consider once that Klay Thompson gets back, not this upcoming season, but next year, they might be right back in the championship picture.

Stephen A. Smith: (48:14)

When you look at Portland, they picked up Robert Covington to pair with CJ McCollum and Damian Lillard and those boys. You can't ignore them either. As the Western Conference, I would say Phoenix to answer your question directly. In the East, you've got Philly, Boston, Toronto, Miami and Milwaukee, especially with the Greek Freak agreeing up for the five years, $228 million for the-

John Darsie: (48:33)

Were you surprised about that? Were you surprised about him re-upping?

Stephen A. Smith: (48:34)

I was a little surprised because I thought that he would weigh his options. I thought that Pat Riley in South Beach would have a chance, but if you saw the documentary on him and his family, how poor he was, how much they struggled and starved and what have you, to be embraced by the Milwaukee community the way that he was, for the organization to do things for his family, like his brother is on the roster for crying out loud, no disrespect for his brother, but there's no way in hell his brother would be on an NBA roster if it were not for him, but that's the case. They took care of him in every way. And so they appealed to him in a way that said, hey, you know what? He's like, I'm in a great, great situation. They love me. So I'm going to stick with that.

Stephen A. Smith: (49:20)

I look at those teams and Milwaukee, anybody can come out from those teams, Milwaukee, Boston, Miami, affiliate of four. We'll see about Boston even though I love Jason Tatum and Jaylen Brown, I question their depth. But the team that I'm looking at right now is Atlanta in terms of what could end up happening to them. I mean, this was a horrible team last year, but Trey Young could really, really play. They've got some other pieces. They just added Rondo to their squad as well, who's a guy that knows how to run a basketball team. And so you got to keep your eyes on one of those up and coming teams. Not that they're going to win the championship or anything like that, but that they could make things interesting than it once was.

Anthony Scaramucci: (50:01)

We knew the kid was going to get signed because we had Mark Lasry, the owner of the Milwaukee Bucks on a SALT Talk. And you could tell from the way he answered that question, he wasn't letting that kid out of Milwaukee.

Stephen A. Smith: (50:13)

Right. Well listen, all you can do is offer them all the money in the world, but it's up to them to take it or not. In the case of Kevin Durant, he turned it down. In the case of LeBron James, he turned it down. In the case of Anthony Davis, he turned it down. So it wasn't a matter of the money because you knew that they were going to offer him the max. It was just about what he wanted to do, but he said it best. He said, they embraced me when no one else would. They were looking at me, they saw this kid out of Greece. You got to remember the Greek Freak, he's gained 57 pounds of muscle since he arrived in the NBA. He's a freak of nature that ... No one saw that coming. No one saw that coming.

Anthony Scaramucci: (50:53)

Stephen, see if you can get me introduced to his trainer, can you help me with that? Because I need 57 pounds of muscle.

Stephen A. Smith: (51:00)

I don't think any of us need 57 pounds of muscle at this age, but I will tell you this, I can use some of those muscles. Ain't no doubt about that. I can still use a stamina. I can tell you that.

Anthony Scaramucci: (51:09)

Tough kid. Well, you've been absolutely terrific. Thank you so much for joining us on SALT Talks. I wish you and your family an amazing Christmas holiday and great New Year's. Hopefully we'll get you back. We got a lot to talk about. We could have 20 SALT Talks with you, Stephen A.

Stephen A. Smith: (51:27)

Well, thank you so much. I appreciate it. And if you don't mind me giving myself a plug, remember Stephen A's World debuts on ESPN+ January 11th, Monday, January 11th. I'll be on every Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday, because I'll still be doing my NBA show on Wednesday.

Anthony Scaramucci: (51:45)

Twitter handle? What's your Twitter handle?

Stephen A. Smith: (51:47)

Oh, @stephenasmith.

Anthony Scaramucci: (51:47)

All right.

Stephen A. Smith: (51:47)

All right.

John Darsie: (51:47)

Stephen A's World, go out and get that Disney bundle. I have three young kids, Disney+ is a hit in my household. I got my ESPN+ for when they go to bed and I can consume some sports content and you also get Hulu is the best deal in the world. And now let's make Steven's parent company happy. Go and get that Disney bundle and watch Steven A's World on ESPN+ starting January 11th.

Stephen A. Smith: (52:13)

Thank you so much. I appreciate it. Oh, by the way, I want to say this to y'all too. Not only am I hosting it, I'm the executive producer of it. And my production company is co-producing it, Mr. SAS Productions. So I'm the executive producer, the host and co-producing it as a company. I'm stepping into your world, Anthony, I'm trying to learn from you now.

Anthony Scaramucci: (52:33)

Now, I know it's going to be super successful. I knew it before that, but now I triple know it.

Stephen A. Smith: (52:36)

I'm glad, man.

Anthony Scaramucci: (52:38)

Well, you be well. God blessed you, mam. Hopefully we can get you to one of our live events before too long.

Stephen A. Smith: (52:42)

Absolutely. Looking forward to it. God bless and happy holidays to y'all.

Anthony Scaramucci: (52:45)

You too, brother. Thank you.