"I’m very concerned about extremism among the military, armed forces and veterans. Domestic terrorists have leaned on this vigor for patriotism… they've exploited it to the point where they've found believers.”

Retired Lieutenant General Russel L. Honoré was brought in to review the security failures surrounding the January 6th Capitol attack and offer recommendations. He gives his thoughts around the insurrection and warns about a scenario where more lives could’ve been lost. LTG Honoré expresses his concern about the rise in extremism, especially among police, military and veterans. He sees internal fractures as damaging to a nation that has lost a shared sense of purpose, exacerbated by disinformation and misinformation. He offers some of the lessons he’s learned about leadership over the course of his distinguished 30+ year military career that included famously his vital leadership in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

LISTEN AND SUBSCRIBE

SPEAKER

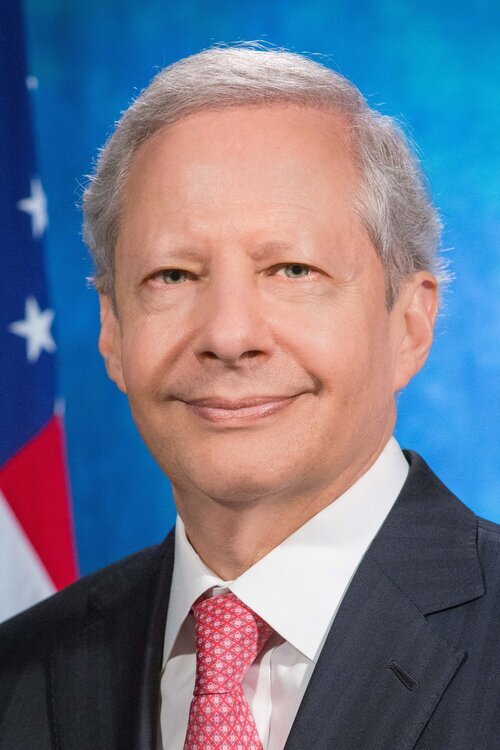

Russel Honoré

Leader

U.S. Capitol Complex Security Review

MODERATOR

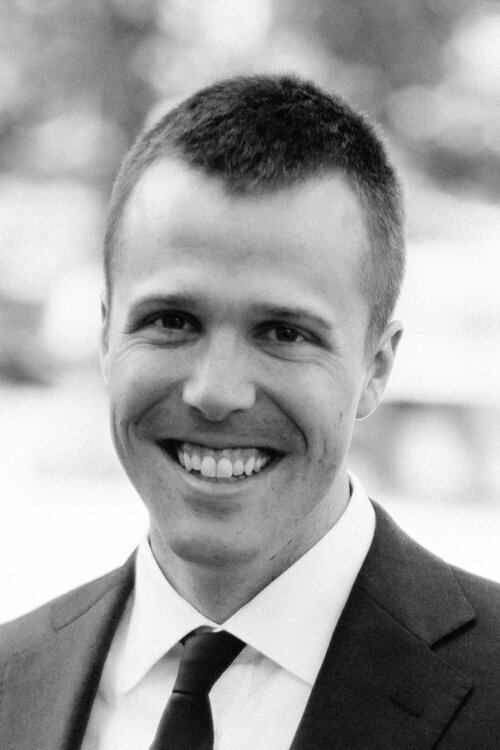

Anthony Scaramucci

Founder & Managing Partner

SkyBridge

TIMESTAMPS

0:00 - Intro and background

6:30 - Capitol attack security review

10:02 - Extremism among police and military

14:12 - Country’s internal fractures

27:43 - Capitol security mistakes and recommendations

36:05 - Leadership and human behavior

TRANSCRIPT

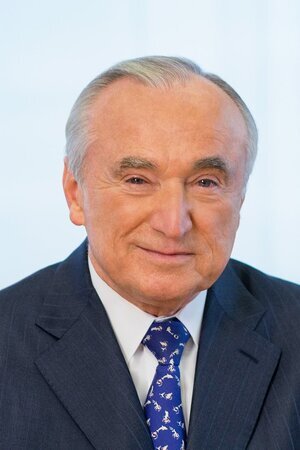

John Darcie: (00:08)

Hello everyone. And welcome back to salt talks. My name is John Darcie. I'm the managing director of salt, which is a global thought leadership forum and networking platform at the intersection of finance technology and public policy. Salt talks are a digital interview series with leading investors, creators, and thinkers. And our goal on these talks the same as our goal at our salt conferences, which we're excited to resume in September of 2021 here in our home city of New York. But that's to provide a window into the mind of subject matter experts, as well as provide a platform for what we think are big ideas that are shaping the future. And we're very delighted today to welcome, uh, Lieutenant general Russell L honorary to salt talks, uh, Lieutenant general Ray, uh, helps organizations develop a culture of preparedness and creates the mindset of problem solving. Take charge, take charge leaders in the age of COVID 19 and the U S Capitol complex breach.

John Darcie: (01:05)

Uh, he's an American hero who helped, uh, new Orleans city recover from catastrophe after hurricane Katrina. He's been chosen to lead the security review of the U S capital security infrastructure, uh, inter-agency processes, uh, procedures and command and control, uh, general honor rate now shares candid and colorful leadership views on how government resources, the private sector, and we, as individuals can work together to overcome the current challenges facing the world as the commander of the joint task force, Katrina, uh, Lieutenant general Honore Ray became known as the category five general for his striking leadership style in coordinating military relief efforts in the post hurricane new Orleans. He's a decorated 37 year army veteran and global authority on leadership. Uh, when hurricane such as Harvey Irma and Maria approach news networks like CNN, Fox, MSNBC, and CBS consider him their go-to expert on emergency and disaster preparedness. And just to reiterate what Anthony said, uh, before we went live, he's truly an American hero and one of the best among us. So we're extremely grateful for your time, general and grateful to have you here on salt talks hosting today's talk is Anthony Scaramucci, who is the founder and managing partner of SkyBridge capital a, which is a global alternative investment firm. He's also the chairman of salt. And with that, I'll turn it over to Anthony for the interview.

Anthony Scaramucci: (02:24)

Well, John, thank you general. I know you're from a very small family and so I want to start right there. Tell us about that family of yours. Where were you born, sir? Uh, how many kids were in that family and, uh, and how did you get yourself into the American military?

Russel Honoré: (02:41)

Well, good boy is great to be with you honor to be with you. I was born in a little place called Lakeland, Louisiana as right at the end of the Bush road, right next to the Alamo plantation of big sugar farm, where we, uh, formed about a hundred acres on a subsistence farm. And I say subsistence opposed to sharecropper's farm because that was a different setup. We rented land. My father and mother had 12 children. I was number eight street boy in the family. And, uh, growing up, uh, poor in south Louisiana on a subsistence farm. Uh, you miss some of the skills I needed to adapt and overcome in the army. Uh, when you're poor and you live on a subsistence farm, you learn how to fix things. Tony Anthony, uh, w w one time we had two televisions to old black and white TV and one had sound and one had a pitcher and the young and the dumbest was setting up that mood and Tanner.

Russel Honoré: (03:41)

I was some aluminum fall on it. So when I came in the army, those skills, uh, were useful to me because you learned to adapt and overcome, but growing up also in that family, you're a little stand there's a hierarchy, uh, in, in the group because a family of 12 is like a team, or it could be like a herd if you get out of line. And, uh, that was a, a productive way to grow up. I wouldn't want to do it that way again, because there was many downsides to it, but it certainly, uh, add to the old adage. You know, you don't sharpen a knife with a clause, you sharpen it with a stone. And it taught us all, some lessons that what we get out of life, we're going to have to earn. And it reinforced what our public school teachers told us.

Russel Honoré: (04:33)

Anthony, if you get an education, nobody can take that from you. And you can do anything you want in America. If you get an education and apply yourself, that's it. I was the first one in my family to be able to graduate from college. Uh, but also say all my other brothers, uh, were more wealthy than I was because I chose to come in the army and, you know, get rich in their heart. They will mostly in the trades. Uh, it ended up being contractors, build houses and in the skill. So that's a basic root of my big go-to. What is known now as segregated schools. Again, uh, some people, uh, we spent a long time to get rid of them the second equal, but I think I learned some great lessons from that and they continue to serve me today. And that is, uh, you can't drive this bus looking in the rear view mirror. We got to look forward. We have to take those experiences and use them to not let bad things happen again, but let's move forward. Let's improve our country. And let's treat everybody with dignity and respect is what I learned from many spirits. And I apologize for that long answer.

Anthony Scaramucci: (05:45)

No, I loved it. I wanted to let you keep going. I think it's a brilliant answer. And it, it speaks to your compassion and your empathy for people. And also your aspirational thinking. I want to shift gears though, sir, because, um, we're in a time of a peril for our democracy. That's just my opinion. So I'll share that with you in January. Uh, it was actually my 57th birthday, the 6th of January. Uh, we witnessed a insurrection at the nation's Capitol, um, speaker Pelosi appoint to you to lead a review of the security failures during that insurrection. Uh, why, why do you believe, sir, that it's important to take into account? What happened on that day

Russel Honoré: (06:31)

Is important because if it was not for the work at the tactical level, the front line officers, uh, as well as the DC police, metropolitan police force and a couple other small tactical boobs that didn't happen. Uh, this could have been a total disruption about democracy while it delayed it in terms of time. And it's an embarrassment to our nation because we go around the world preaching to other nations, the peaceful transfer of power. And here we are United States of America. Who've preached everybody about peaceful trade for a poem. We not having one. We lost our innocence that day.

Russel Honoré: (07:26)

And just, just one more point on that had those officers had not put their body on the line at the, and the insurrectionists that God do. Those two boxes. I don't think he would have, uh, changed the outcome of the election, nothing else, but it's certain the hell would have been a major disruption. Or if the mob had gotten to the vice president or to the speaker, it would have turned into a bloody affair by that time. And I'm glad it did not turn into a bloody affair, but it leads to the point. We can not let this happen again.

Anthony Scaramucci: (08:08)

We, we had a situation where the rioters entered the Capitol building. Some of them look like they had weapons and zip ties on them out. How close do you think the situation was to becoming exponentially worse?

Russel Honoré: (08:26)

Uh, again, I thank you for the principals have been attacked or had been, uh, uh, taken that would have made it exponentially. And I think it would have been at that point in time where a shooting would have started at a lot higher rate than we saw with that one person who got shot, trying to get into the flow on the floor, that in spite of everything had had this happen in any other country that I know of. And you could just name one. Uh, there would've been a lot of people did that day. And I think all of, uh, uh, cultural shift to try to get officers to deescalate things or not be a degree, not realize we might've gone a little too far, cause we didn't have the not lethal weapons ready. They weren't properly trained on them. They weren't probably maintain. And I think there's some soul searching going on in the federal law enforcement community. There's certain lines we cannot allow to be violated. And if you violate those lines in my new mantra to the Capitol police hold the line, there's some lines that cannot be broken and bomb rushing. The capital is one of them because when the Capitol close of democracy stopped,

Anthony Scaramucci: (09:58)

Are you, are you concerned about the rise of extremism in the United States?

Russel Honoré: (10:03)

Yes. In a Bergen son of an among our people in the military and people in the armed forces and our veterans, uh, for a long time, culturally, we have held, uh, law enforcement people are veterans and those who serve in the military, they're in the highest esteem. But what we're finding out in reports released by the FBI and other government agencies and the department of defense, uh, the people who want to, uh, the domestic terrorists crowd has leaned on this, uh, vigor for patriotism and saving the nation. And we're the last line to police the veterans and those in uniform. And they have exploited that Anthony to, to a point where they have found believers in the military, they found believers in the veterans. And if I believe in subservient police that in order to save the nation, uh, Bemis joined this movement to challenge the results of an election, which is the basic underpinning of a democracy.

Russel Honoré: (11:29)

You know, democracy is based on trust. Look at many things we do based on trust. You know, we, we get on the phone, we give somebody out number and they take money out of our account. You know, w we go to the polls, we hit a button and we vote who we want. Imagine all that's based on trust. And the insurrection is I've to take out innocence because without trust in a democracy, the democracy won't work. But when that trust is challenged, as it was after the 2012 and 11 election, and the process work judges, uh, defense attorneys and attorneys on both sides go in and they run the machines and it still is no trust because of this agitation that they didn't like the results of the election. And we lose that level of trust in America. We might still have them a democracy, but it won't be worth living in that.

Russel Honoré: (12:31)

There has to be a level of trust that when government officials stand up and tell the American people something, that it is the truth, the way they know it now, because the truth does change. I'm not stupid. You know, when we looked at this COVID thing, we been through the true change many times, uh, but we also know there was some misinformation put in there that caused people to question when they see relatives die. And they're not sure if they get the real truth or they get another version of some misinformation thrown at them. So again, I apologize for long answer there, but that was a barrier. I was a very deep question. You asked

Anthony Scaramucci: (13:17)

Great answers general. I, I, I'm not interrupting you because I want to hear what you have to say. You have some brilliant insight. I don't want to make this political. I know this is really about the security issues and the security shortcomings inside the Capitol. But I'm wondering if the information issue that you're describing, not just related to COVID, but also the political information and the facts that get misconstrued, uh, where we as a nation sometimes now are, are actually, we can't even argue or debate because we can't even agree on the facts are. And so what, I'm, what I'm wondering, based on your experience, your love of country, what are some things that the United States can do to try to reconnect itself and to bring back that civic virtue, uh, that, that you've basically lived your life by how do we do that, sir?

Russel Honoré: (14:13)

Well, I'm not quite sure if I have a good answer for that. That's why we've got the soul talks. And, uh, you'll bring a future desk who probably written books has spent their life studying that. I do know the basic underpinning, the patriotism, as I learned it, that you love your country sometime when your country don't love you, or it may appear that way. And, uh, you know, we owe the Supreme court in the highest esteem, but I remember as a young boy when the Supreme court said separate but equal was okay. Yeah. So, but things have changed. And I think they've changed. Continue to change for the better, but we've got to understand it's not just the disruption that was going on between people and trust in our country, that this is being influenced by outside agitators. And I do believe that there is foreign intervention to see that a democracy like ours does not survive because there are strong people in power in other nations, influential countries around the world.

Russel Honoré: (15:29)

I mean, what China has put their president for life and the elections that happened in Russia or a perfunctory thing that just keep electing the same guy. And he puts his opposition people in jail. There's a big push, not to have a democracy like America being neat, the beacon for democracy around the world. And they're, they're Indian. They're influencing people in the hinterlands in America because they are coming in through the internet. They're coming in through social media. And you know, the thing that really scares me, they're reaching out youth, they're reaching young people. They're, they're young people. When I grew up, I was in the four H club and the future farmers of America.

Russel Honoré: (16:22)

That was it influenced by some great teachers and coaches that talked about leadership that talk about love of country. And when we stood there, pledge allegiance to the flag, there wasn't a pin dropped in the room. There was no sidebar conversation. Now, young people are being influenced by going on the internet. And somebody spewing, vitriol hate among people because of their diversity because of their religion. I wasn't exposed to that, but I know my children and grandchildren are, and I know many people across the country and that information operation is attacking our country 24 7, and it's not bad. They do it one time. They save it on YouTube and people can go back and watch it again. And that's why it's important to have programs like yours, that try to bring information to people that we have to be aware of this outside influence in our government and in our culture, it could change America.

Russel Honoré: (17:41)

And, but I do have a belief that every generation in America, as a war to fight the greatest generation, fought it in Omaha beach. This generation will be fought in information operations and then influencing from people from afar, because the greatest threat to a democracy from our, like ours is a threat from one end when people lose competence in the government. And we see that happening, that the people are questioning the veracity about elections questioning. Where did the virus come from? Questioning the significance of the vaccine? Everything is challenged because that steady stream of information from the outside has one thing in mind. And that is a disruption of the United States. As we know it,

Anthony Scaramucci: (18:39)

It's not just from the outside, sir. We have political leaders in our country that are fomenting, those lies. Uh, they could be fomenting, those lies related to the vaccine. They could be fermenting them related to the veracity of our electoral process and the legitimate, legitimate seas of our election. And so, um, you've called for, uh, some, some people to be put on no fly lists that are, uh, potential threats or potential dead mesic terrorists. And these could even be people that are former military people, as you just pointed out or people that are formerly with our police departments, uh, state and local police. Um, I, and I'm not asking you to wave a magic wand and none of us have it, but if you were the czar and you could lay down some of the tenants, the groundwork to reunify the country, uh, one of the great things about the army is that people are coming from all the 50 states.

Anthony Scaramucci: (19:37)

They unify and bond together in the army. You know, you mentioned the, uh, world war II, my uncle Anthony, who I'm named after he was on Omaha beach. He, he was, uh, he was a decorated veteran purple one, the purple heart in, in France, on behalf of the country, my uncle Salvador fought in the battle of the bulge. Um, and when they came home, they had friends from all over the country that were part of that effort with them. And they felt more close as a result of that today with less than 3% of the country tied to the military one and a half to 2% in the volunteer services. And then their family members, we don't have that connective tissue that we once had. And so my question, sir, is how do we get it back?

Russel Honoré: (20:25)

Yeah, that's another one of them, a 60 what's that show used to be the $64 million question. And I wish I was smart enough to hell about taking a shot at it. I think we need to almost try to spend an equal amount of time about what's going good in our country. Definitely. You know, there's, uh, there's old song that came out. Uh, is there any good news, a D you remember that it kind of a country reign to it? Uh, I think it's important to, for folks to know that, uh, with all our problems, there are a lot of beacons of light happening around the United States of America. I mean, we've given the world a solution to the virus, which is a shot, uh, that if people take it with all the facts we know, and I had in myself, I had my first shot on Christmas Eve and never doubted because I learned to trust the system.

Russel Honoré: (21:30)

We have to have a, a sufficient amount of trust in a democracy to make you work, that there are a lot of things that are going well, but it's not equally, uh, being distributed among the people where poor people working for minimum wage, uh, struggling Lang hell, uh, because we're still using last century opinion equity. When I talk to CEOs, uh, Anthony, about, uh, creating teams in the companies and you create teams by making sure everybody understand that everybody in the company is equally important. Whether it's the guy down in the computer room, that's watching the blades to make sure they run right, or the security guard at the front desk, or somebody in the suite speed. Everybody have to feel equally important in the company and respect. And everybody needs to tie into the mission and to accomplish that mission, we need everybody to do their best, but when the missions accomplish it much like general Washington and his troops who, uh, saved us from the British army.

Russel Honoré: (22:51)

Everybody, when we achieve success must benefit from the bowtie of success. It's not just a soon C-suite that get all the new range rovers or the company acquired new jet. That guy that secured the front door, that front and back office staff that make things happen. Everybody has to benefit from the bounty of success. And I was looking at one of our great companies, Amazon, what a miracle e-commerce. But again, they will look at themselves. If people don't benefit from the bounty of success, they do. I think they lose their connection to the mission. And when they lose the, to the mission, you start seeing the tires come off the truck and the paint start to peel. And I think industry, as well as government need to make sure that we are being inclusive of everybody in the country. Look what happened with the essential workers, how many people paid respect to somebody who check your groceries out at the store of Della pet, Debbie gap, or in the hospital.

Russel Honoré: (24:17)

The president maybe did not graduate from high school or got a GB that's coming in and cleaning up elderly and sick people, or the person that maybe did not make it through nursing school, but now wanted to help others from the heart and in an elderly home taking care of, of, uh, elderly patients with multiple, uh, health issues, dealing with the guy that cut the meat in the slaughter house and the truck driver. I think it gave the next generation in appreciation that, yeah, my dad's a truck driver, but without that, Trump, you don't get your high screen TV. You don't get that new of foreign car you bought, you don't get bread on the table. You don't go to the restaurant and get it. I think we have to capture that and ensure that we are bringing this forward as a lesson from operating in an economy under a pandemic for a year to being more inclusive of everybody being on the team.

Russel Honoré: (25:34)

And when the country succeed, when the company succeed, everybody needs to, uh, participate in about ease of success. And we got some work to do there, and that's hard to do the way we've constructed our economy and the way we've constructed, uh, uh, how we help people who need help. Like it would have been a no brainer 10 years ago to declare pre-K education as a national standard. What the hell, you know, five years ago, we should have been playing, uh, junior college and skills, a no brainer. You just go to school and we need to fix that. And we're going to continue to be the innovation leader in the world. That's the message I tell CEOs.

Anthony Scaramucci: (26:34)

It's a great, great message. I appreciate it, sir.

John Darcie: (26:38)

General honor. Right. Uh, Anthony gives me the privilege of asking some on these talks. So I'm going to jump in with a few follow-ups you talked about on January six, how the Capitol police, they both suffered from a lack of organization and preparedness, but also there was, you know, heroes on the front lines of that situation that prevented it potentially from becoming bloody, um, and, and people, more people losing their lives. As a result of that day. What specifically in your findings did you find today, you know, mishandled from a preparedness perspective, how can they improve on being more prepared for similar types of situations? One of your recommendations also was putting up a fence around the perimeter of the Capitol in the short term, to try to address all these sort of systemic, uh, vulnerabilities in the system. Is that going to be a permanent function of our society, whereby we're going to have to construct fences and put up barbed wire to prevent sort of domestic terrorists from, uh, you know, committing murder or, or other crimes, or are we going to be able to find a way to deescalate things at a more systemic level to prevent that

Russel Honoré: (27:44)

I've been around the world a few time, John, I'm glad you asked that question and there's no other national capital that you can just walk up to show your driver's license or your teacher sign you in and scroll around the Capitol. No other, have you, no one tell me where it is. We've preserved something through to 246 years of, uh, of our nation, that few other democracies or any other government would allow. And that is the right for citizens to come to the capital, because one of the cultural things that every member on both sides, the house and the Senate, which is odd to them to agree on what time of day it is. That's the lesson I learned that we ought to talk about a little bit sometimes and the two party system, and they all agree on. We want the Capitol open to the public at the same time general.

Russel Honoré: (28:53)

We don't want another ability for one six for Bob to rush to capital and disrupt our democracy and put people's lives at risk and people losing their lives. So that's the underpinning challenge. What we found was it, what happened before during the bed, uh, what happened before most of our operations start with, uh, prepared and then how do we prepare? What are the threats? And there was an assumption by the Capitol police board, that the crowd that was a symbol under a former president, Trump would not be violent. That assumption, uh, his words, I'm using their words that they use the testimony. I'm not making this up. No, was it our job to look at this, our job was to recommend what needed to be done to prevent this from happening again, intelligence. It was a failure in intelligence. And I think that failure is systemic because even yesterday, you saw, I saw a watch. The hearing with the FBI director said, well, it was just internet chatter, wake up, dude.

Russel Honoré: (30:16)

In the 21st century internet challenge, chatter is intelligence. We're still going back to that vision of intelligence of some world war two, where you got a guy straightened on the island, but he can listen in on the Japanese. So the German ready on that. And that's the kind of intelligence they're looking for. They say they come in at Dawn, right? There's at least six shifts. This is the direction they are moving in. That is America's vision of intelligence. Rido believe in when it's in plain sight, they didn't believe it an hour before the attack. When people said go to the Capitol, they still didn't believe it that'd be a BI in their transition or what they had. That was on Chad, the Capitol police major problem with handling intelligence. And we recommended that they include so many officers in intelligence that the rework, how they use intelligence and redefine what they think is intelligence, because they are looking for intelligence derived in a folder with secret marks on it, where the, where the, uh, uh, plastic step, when you got to open it, and you send everybody out the room and you look down and you look at the stores, that's not intelligence in the 21st century.

Russel Honoré: (32:01)

We have trouble dealing with people operating in plain sight because as American, we confuse television programs like the west wing with real life, we could fuse programs like in CIS that we know everything that's going on, but if it's happening in plain sight, it can't be that bad. And our big, our entire, uh, intelligence gathering system in America, uh, need to be refocused because doing it in plain sight, people coming on television say we got her to Capitol. They're sanding on it. And we discarded that. And we know what happened, John, as a result of that, uh, there was an intelligence failure. There was a failure on the part of the training of the officers in the capital. We recommended adding officers. The capital at the day of the attack was about 183 officers shot some of it from COVID. And some of it, they didn't have a class.

Russel Honoré: (33:08)

Last year, they were shot at the authorization. We recommended adding several hundred officers to the Capitol police force. Because last year they consume 700 at 20,000 hours over time. And you and Anthony nil looking at businesses, if you use it that much overtime, you probably need to hire some more people. If you use that much overtime, people are working six, seven days a week and that needed to be fixed. So they don't have time for training. We also recommended those fences. You talk about, but we're not talking about the green zone fences you saw around the Capitol. We're talking about re-engineering fences through with the core engineer is some of the land's best landscapers we got in the country and in the world to bed those fences in the ground. So if we saw something coming like happened on one six, that fencing could come up, give law enforcement time to respond, to get enough officers there. So people clearly know you violate this fence, you're going to be arrested, or you going to be shot.

Russel Honoré: (34:18)

That sign has to be on the fifth. You violate this line, you got to be arrested, or you will be shot. You can't violate the line. But as you saw, what we had was a equivalence of bicycle fences that we put up the control parades, and that was inadequate. It worked for 246 years. It didn't work that day. So we need to be more innovative. And the approach I gave to the core engineers is they think about the Disneyland. Look, you go to Disneyland is one place to come in, one place to go out. And you never realize how the abuse landscaping along with fencing to get you at the right place. And that's the appearance. Cause we don't want the capital to look like the green zone, but we can not allow one six to happen again.

John Darcie: (35:12)

Right. So you sort of became famous in the public consciousness for your response to hurricane Katrina. Um, you know, you came in the government sort of initially bungled elements of the response. There was anarchy in certain parts of new Orleans. There was a, a great podcast mini series that I've recently listened to from the Atlantic about the entire situation, but you came in and you took control of the situation. Uh, but what did you learn from that experience about human nature, about how people sort of naturally respond to adversity the way disinformation spreads, um, in a stressful environment and how to sort of remedy that environment that could apply to something like a capital insurrection. It could apply in business. It could apply, uh, in public policy, but what did you learn about human nature from that experience and how to take control of complex situations?

Russel Honoré: (36:05)

Yeah. Are they people from that experience and many others in military experienced 37 years? I think people are looking for somebody, Ooh, is a leader that is got to take responsibility for what they say. And I had the unique, uh, position, uh, not being an elected officer. No, I'll I'll, I wasn't elected by the people. And I was unencumbered by worried about if I was going to get elected again. And that's a hell of a burden. Our politicians carry. That's why I would never be a politician because they have to worry about how this is going to affect it. Then next, uh, election cycle. And because Omar Rabo a Tuesday evening or Wednesday morning in new Orleans, uh, I realized that the mayor knew all this. He's a senior elected official. That's what they teach us in the military and you help them do what they gonna do. And the senior person in Louisiana was the governor. There wasn't a president, they were in charge. And I think people were looking for by that time is, this is what we go to do. This is what we go to do it. Now, go make it happen.

Russel Honoré: (37:44)

Uh, because then when people are looking for a leadership is a execution. That leadership is not about getting people to do what they want to do. Leadership is about getting people do what they don't want to do. Hell you can get everybody to take off early on Friday or go to lunch together with you at the, at the lobster festival Thursday. But how do we lock down and said, Hey, we got a 36 hour close down here. And I know some of you were planning on going to the beach or spending time with your family. We've got to get this done. Leadership has got to get people to do what they don't want to do. And more of the, not politicians want to tell people what they want to hear now, what they want to do. And it's very ingrained in our politicians not to take responsibility.

Russel Honoré: (38:44)

Look, the hurricane broke the city. You don't have to defend that. The hurricane one, we lost go with that as opposed to saying, well, the state didn't give us what we needed. Are we still waiting on the federal government? Hey, look, the hurricane broke your city and put 17 foot of water in it, but it needed a thing. The president can do about that right now, other than to help you. But there's something we've taught in the political coast, Anthony, and maybe you can help fix that. That regardless of what the disaster, uh, blaming some branch of government at the time is happening is not the right answer. And too much of that was happening. And people didn't know who to listen to. We listened to the bearer or do we listen to the governor or do we listen to national media who flew in on the corporate jets, got in there and basically beat me there.

Russel Honoré: (39:52)

So that was some substantive problems. We gotta deal with it. We have dealt with, but I think people in a disaster, uh, looking for the voice in nine 11, there was a mayor of New York who said, you know, burn his candle out. But people were looking at him. People were looking at the, our president, president Bush, when he said this will not stand. And they will hear from the American, but people, he wasn't. And he laid the hammer down on those. You attacked our country. Are they, people are looking for those moments. And people are held in high esteem. When someone woke up and said, we've got to work on this together. And as opposed to, uh, different levels of government saying different things. And as we saw the days and weeks after Katrina, it became the blame game. And I wouldn't play in the blame game. We're here to save lives and take care of people.

John Darcie: (40:52)

Yeah. We, we built great institutions in this country that we think are resilient, but leadership matters. And, um, you know, I think, you know, we're experiencing that, but, uh, Lieutenant general, Russel Honore, it's such a pleasure to have you on salt talks. Uh, we could go on for hours with you, uh, extracting your wisdom, but, uh, we hope to see you on the media, still talking about the insurrection, talking about these issues that are facing the country. I think you have clear eyes about everything that's going on. So, so we need your leadership more than ever, but thank you so much for joining us

Anthony Scaramucci: (41:23)

General. You mentioned people's candles burning out your halogen lights. Sure. Sur is shining very brightly. Okay. We want to make sure we keep you in one of the main focuses of our country. You're a national treasure and it's a big honor for us to have you with us today. Thank

John Darcie: (41:44)

You be well, sir. Thank you everybody for tuning in to today's salt. Talk with Lieutenant general Russell on array. Just a reminder. If you missed any part of this talk or any of our previous salt talks, you can access them on our website on demand@salt.org backslash talks or on our YouTube channel, which is called salt tube. Uh, we're also on social media. Twitter is where we're most active at salt conference. Hopefully not spreading any, uh, disinflation there. Uh, but we're also on LinkedIn, Instagram and Facebook. And please spread the word about these salt talks, these conversations in particular like the one we had, uh, with the general today, just understanding what it takes to combat some of the polarization and extremism rising in our society today, we think are, are very important. Uh, but on behalf of Anthony and the entire salt team, this is John Darcie signing off from salt talks for today. We hope to see you back here again soon.